Promotion

Use code SPRING26 for 20% off sitewide.

By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

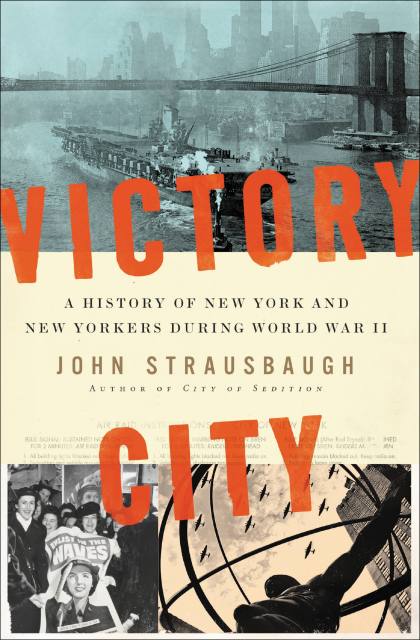

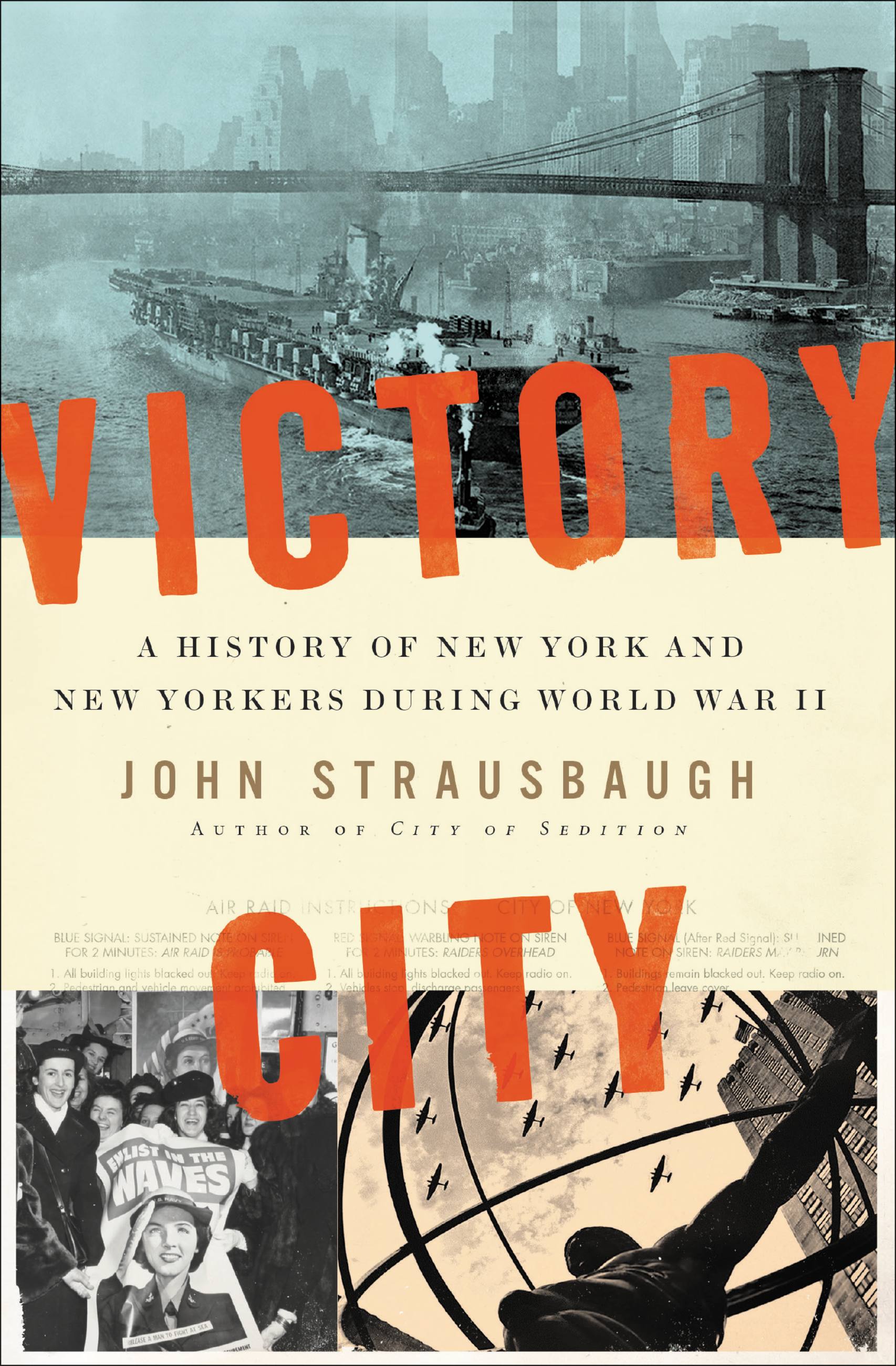

Victory City

A History of New York and New Yorkers during World War II

Contributors

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Dec 4, 2018

- Page Count

- 384 pages

- Publisher

- Twelve

- ISBN-13

- 9781455567461

Price

$11.99Price

$15.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $11.99 $15.99 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged)

- Trade Paperback $17.99 $22.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around December 4, 2018. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

New York City during World War II wasn’t just a place of servicemen, politicians, heroes, G.I. Joes and Rosie the Riveters, but also of quislings and saboteurs; of Nazi, Fascist, and Communist sympathizers; of war protesters and conscientious objectors; of gangsters and hookers and profiteers; of latchkey kids and bobby-soxers, poets and painters, atomic scientists and atomic spies.

While the war launched and leveled nations, spurred economic growth, and saw the rise and fall of global Fascism, New York City would eventually emerge as the new capital of the world. From the Gilded Age to VJ-Day, an array of fascinating New Yorkers rose to fame, from Mayor Fiorello La Guardia to Franklin and Eleanor Roosevelt, Langston Hughes to Joe Louis, to Robert Moses and Joe DiMaggio.

In Victory City, John Strausbaugh returns to tell the story of New York City’s war years with the same richness, depth, and nuance he brought to his previous books, City of Sedition and The Village, providing readers with a groundbreaking new look into the greatest city on earth during the most transformative — and costliest — war in human history.