Promotion

Use code SPRING26 for 20% off sitewide.

By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

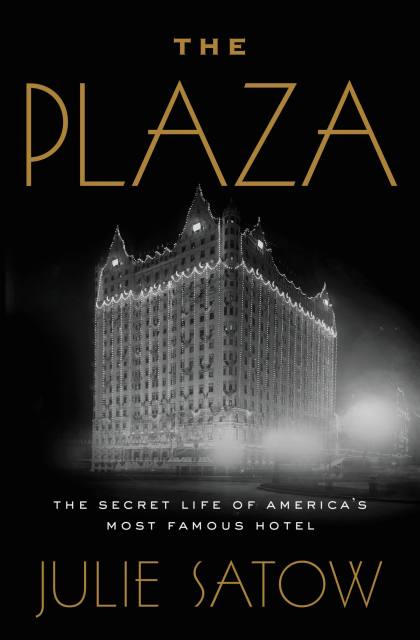

The Plaza

The Secret Life of America's Most Famous Hotel

Contributors

By Julie Satow

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Jun 2, 2020

- Page Count

- 384 pages

- Publisher

- Twelve

- ISBN-13

- 9781455566655

Price

$19.99Price

$24.99 CADFormat

Format:

- Trade Paperback $19.99 $24.99 CAD

- ebook $12.99 $16.99 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged)

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around June 2, 2020. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

Journalist Julie Satow’s thrilling, unforgettable history of how one illustrious hotel has defined our understanding of money and glamour, from the Gilded Age to the Go-Go Eighties to today’s Billionaire Row.

From the moment in 1907 when New York millionaire Alfred Gwynne Vanderbilt strode through the Plaza Hotel’s revolving doors to become its first guest to the afternoon in 2007 when a mysterious Russian oligarch paid a record price for the hotel’s largest penthouse, the eighteen-story white marble edifice at the corner of Fifth Avenue and 59th Street has radiated wealth and luxury.

For some, the hotel evokes images of F. Scott Fitzgerald frolicking in the Pulitzer Fountain, or Eloise, the impish young guest who pours water down the mail chute. But the true stories captured in The Plaza also include dark, hidden secrets: the cold-blooded murder perpetrated by the construction workers in charge of building the hotel, how Donald J. Trump came to be the only owner to ever bankrupt the Plaza, and the tale of the disgraced Indian tycoon who ran the hotel from a maximum-security prison cell, 7,000 miles away in Delhi.

In this definitive history, award-winning journalist Julie Satow not only pulls back the curtain on Truman Capote’s Black and White Ball and The Beatles’ first stateside visit — she also follows the money trail. The Plaza reveals how a handful of rich dowager widows were the financial lifeline that saved the hotel during the Great Depression, and how today, foreign money and anonymous shell companies have transformed iconic guest rooms into condominiums that shield ill-gotten gains, hollowing out parts of the hotel as well as the city around it.

The Plaza is the account of one vaunted New York City address that has become synonymous with wealth and scandal, opportunity and tragedy. With glamour on the surface and strife behind the scenes, it is the story of how one hotel became a mirror reflecting New York’s place at the center of the country’s cultural narrative for over a century.

-

"Julie Satow...digs deep into the forces that took the Plaza from a living center of aspiring social connection tied to the fortunes of American high society to its present status in an atomized era of pitiless transactional globalism."Tina Brown, The New York Times

-

"[A] lively and entertaining portrait...Ms. Satow's book draws the reader in from the start...a superb history of how a once-magnificent property became its own Potemkin village, a grand luxury hotel on the outside, a hollow shell within."The Wall Street Journal

-

"Readers will happily soak up period details and take notes on how the stalwart staff dealt with class snobbery, prohibition and gangsters, wartime privations, the turbulent 1960s, wealthy dowagers, blushing debutantes, persistent groupies, omnipresent prostitutes, and brawling Indian billionaires. This is social history at its best: thoughtful, engaging, and lots of fun."Booklist (Starred Review)

-

"THE PLAZA reads like the biography of a distant relative as much as the history of a landmark building; the hotel feels alive to anyone who loves it. It's a wild and sometimes vicious life, but so affectionately told that you might come out of the chaos still wanting to visit the old place, after all."NPR

-

"The Plaza Hotel has a long, sometimes storied, sometimes sordid history. All of it is compelling. People often use the expression, 'If these walls could talk...' Reading Julie Satow's wonderful and revelatory history of the fabled hostelry, I couldn't help but think that they'd talked -- a lot -- to her."Michael Gross, New York Times bestselling author of 740 Park and House of Outrageous Fortune

-

"Julie Satow's biography of America's most famous hotel is a fascinating tale of spies and sugar daddies, murder and madness, the real Eloise and Donald Trump, rich cheapskates who left 4% tips and Ragtime-era servants fighting for a half day off each week. Satow's story, as elegant as the exterior of this architectural dowager, digs deep into the century of secrets hidden deep inside the Plaza."David Cay Johnston, Pulitzer Prize-winning and New York Times bestselling author of The Making of Donald Trump and It's Even Worse Than You Think

-

"Julie Satow has written the definitive biography of the Plaza Hotel -- and it is a biography, because the Plaza has been a living, breathing part of New York's cultural, political and business landscape for more than a century. She captures the Plaza's glorious, ribald, tortured history in all of its dimensions and offers a thorough and poignant account of almost everyone of note who has passed through the hotel's doors or scrambled to claim it as their own. Elegance, decadence, power, money, greed and dreams have all resided at the Plaza, and this is the narrative that weaves all of that together -- lovingly and knowingly."Timothy L. O'Brien, award-winning author of TrumpNation and executive editor of Bloomberg Opinion

-

"Julie Satow's THE PLAZA expertly shows not only the characters and events that shaped one of New York's most iconic landmarks but how it became a plaything of a global class of uber-wealthy whose questionable finances often ran through tax havens and Swiss bank accounts."Jake Bernstein, two-time Pulitzer Prize-winning author of Secrecy World

-

"In this wide-ranging and compulsively readable book, Julie Satow tells the story of American high society and its many low moments through the narrative of the Plaza. Not since Eloise was written has anyone captured so charmingly the glamour and spectacle attendant on this hotel, but here we find also the seaminess of a place where the rich have manifested their most despicable tendencies and their most naked ambition time and again. The story of the Plaza as told in these pages is the story of New York's last and greatest century."Andrew Solomon, National Book Award-winning author of Far & Away: Reporting from the Brink of Change

-

"In THE PLAZA, Julie Satow has done a masterful job of creating a gripping narrative that spans just over a century. Her meticulously-researched tale starts with a grisly murder, and thus, in quasi-Shakespearean fashion, the reader lurches between the gritty concerns of the union-workers who built the edifice to the extravagant, excessive realm of the Plaza's various owners and inhabitants. Satow has written the stories of their entwinement with its marble halls and notorious grand ballroom in vivid, suspenseful detail."Vicky Ward, New York Times bestselling author of The Liar's Ball and Kushner, Inc.

-

"Throughout this sumptuous, busy history, [Satow] enlightens and entertains with stories and anecdotes that recount the hotel's many famous and colorful guests...An infectiously fun read."Kirkus

-

"Glamorous . . . funny and insightful. Satow's entertaining parade of eccentric characters will appeal to readers curious about real estate and the rich, famous, and weird personalities of the twentieth century."Publishers Weekly

-

"[THE PLAZA] offers a fascinating, in-depth look at the famed New York hotel's history of odd guests and various owners."Vulture

-

"In her thoroughly-researched book, Julie Satow delivers the delicious and engrossing tale of a century of history at the iconic Plaza Hotel, recalling its triumphs, unearthing its secrets, and bringing to life a revolving parade of famous owners and even more famous guests."Meryl Gordon, New York Times bestselling author of Bunny Mellon: The Life of an American Style Legend

-

"Covering billionaires to laundresses, charlatans to lovers, Capote to The Beatles, THE PLAZA captures the pulse and fortunes of 20th century New York. Millionaires such as Vanderbilt, Bloomberg, Trump, and Macklowe enjoyed themselves amidst Scotch whiskey and damask. Eloise's haunt comes to life through Julie Satow's lively writing and meticulous reporting, providing an enticing window into one of America's great institutions."Lisa Keller, professor of history (Purchase College SUNY) and executive editor of The Encyclopedia of New York City, Second Edition

-

"The Plaza is a splendid story of a splendid New York institution. Funny, surprising, intriguing, well-researched, and always candid, Julie Satow has done a wonderful job of bringing to life one of the city's -- and America's -- most beloved buildings...Ms. Satow knows her New York!"Kevin Baker, bestselling author of The Big Crowd and Strivers Row

-

"What do scoundrels and working men, widows and prostitutes, billionaires and murderers all have in common? Meticulously researched and full of stories of crime, duplicity, and deal-making, Satow's THE PLAZA reveals this infamous hotel in all its glory."Sheila Nevins, New York Times bestselling author of You Don't Look Your Age

-

"This is an eye-opening portrait not just of a hotel but of a city."BookRiot