By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

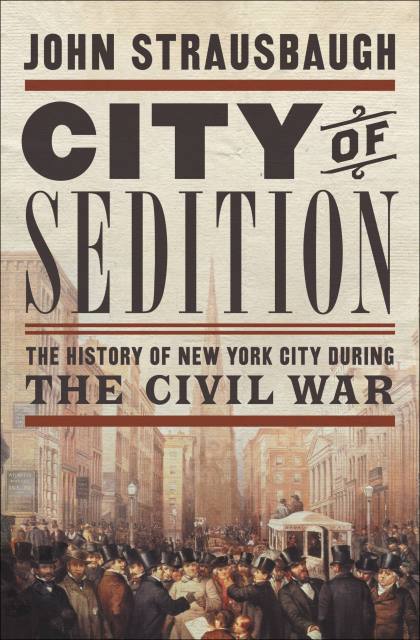

City of Sedition

The History of New York City during the Civil War

Contributors

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Aug 2, 2016

- Page Count

- 352 pages

- Publisher

- Twelve

- ISBN-13

- 9781455584192

Price

$9.99Price

$12.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $9.99 $12.99 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged)

- Trade Paperback $15.99 $20.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around August 2, 2016. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

No city was more of a help to Abraham Lincoln and the Union war effort, or more of a hindrance. No city raised more men, money, and materiel for the war, and no city raised more hell against it. It was a city of patriots, war heroes, and abolitionists, but simultaneously a city of antiwar protest, draft resistance, and sedition.

Without his New York supporters, it’s highly unlikely Lincoln would have made it to the White House. Yet, because of the city’s vital and intimate business ties to the Cotton South, the majority of New Yorkers never voted for him and were openly hostile to him and his politics. Throughout the war New York City was a nest of antiwar “Copperheads” and a haven for deserters and draft dodgers. New Yorkers would react to Lincoln’s wartime policies with the deadliest rioting in American history. The city’s political leaders would create a bureaucracy solely devoted to helping New Yorkers evade service in Lincoln’s army. Rampant war profiteering would create an entirely new class of New York millionaires, the “shoddy aristocracy.” New York newspapers would be among the most vilely racist and vehemently antiwar in the country. Some editors would call on their readers to revolt and commit treason; a few New Yorkers would answer that call. They would assist Confederate terrorists in an attempt to burn their own city down, and collude with Lincoln’s assassin.

Here in City of Sedition, a gallery of fascinating New Yorkers comes to life, the likes of Horace Greeley, Walt Whitman, Julia Ward Howe, Boss Tweed, Thomas Nast, Matthew Brady, and Herman Melville. This book follows the fortunes of these figures and chronicles how many New Yorkers seized the opportunities the conflict presented to amass capital, create new industries, and expand their markets, laying the foundation for the city’s-and the nation’s-growth. WINNER OF THE FLETCHER PRATT AWARD FOR BEST NON-FICTION BOOK

-

"For anyone raised on the notion that, during the Civil War, the northern states stood strongly united against slavery and behind Abraham Lincoln, John Strausbaugh's insightful CITY OF SEDITION will offer a potent and engaging antidote. Training his focus on the vibrant, chaotic city of New York, Strausbaugh sheds valuable light on the ambivalence and complexity with which Civil War America responded to thorny problems of class, race, and disunion."John Matteson, Pulitzer Prize-winning author of Eden's Outcasts and The Lives of Margaret Fuller

-

"An engrossing account of a fascinating time and place in American history. Strausbaugh gives us some of the great figures of the republic, along with Confederate spies, Irish mobs, and some of the most shameless scoundrels in the city's history. A constant page-turner that also delves deep into a complex and surprising era."Kevin Baker, author of The Big Crowd and Paradise Alley

-

"What a terrific job! Strausbaugh paints New York in a vortex of treason and war, profit and chaos, idealism, energy, and murderous violence. CITY OF SEDITION is bright, urgent, and fast as a fire truck."Richard Brookhiser, author of Founders' Son: A Life of Abraham Lincoln

-

"For Abraham Lincoln, New York City was both a boon and a bane: a source of vital support and bitter recrimination. In this gripping, highly original book, John Strausbaugh guides us through a city at war with itself-a tale he tells with nuance, verve, and great discernment."Kevin Peraino, author of Lincoln in the World: The Making of a Statesman and the Dawn of American Power

-

"John Strausbaugh's new work opens the door . . . as no book has done before. Deeply researched and written with flair by an acknowledged authority on the history of the metropolis, CITY OF SEDITION leaves no doubt that 150 years ago New York was already 'a helluva town.'"William C. Davis, author of Crucible of Command: Ulysses S. Grant and Robert E. Lee-The War they Fought, the Peace They Forged

-

"CITY OF SEDITION is a rich feast of outrageous incidents, larger-than-life characters, and often astonishing revelations. John Strausbaugh expertly reveals how a deeply divided New York gave Abraham Lincoln 'more help and more trouble' during the Civil War than any other city in the Union."Gary Krist, author of City of Scoundrels and Empire of Sin

-

"This capstone urban study of superb scholarship is highly recommended for U.S. and regional historians, Civil War scholars, metropolitan specialists, and general readers alike."Library Journal, Starred Review

-

Strausbaugh - journalist and free-range historian, author of rousing books on Greenwich Village, racial appropriation, and geriatric rockers - reexamines a strange chapter in city history that's not exactly unknown...but rarely seen in full...Edifyingly fascinating.Vulture.com

-

Strausbaugh...flanks the era's familiar protagonists with a boisterous chorus of idiosyncratic New Yorkers...in this kaleidoscopic, detail-filled account.The New York Times

-

"...a richly layered and often surprising history, as crowded and fast-paced as a Manhattan sidewalk."Shelf Awareness

-

Populated by an epic cast of characters lurching through evocative tableaux at a breakneck pace, Mr. Strausbaugh's book stands alone, but never still.The Wall Street Journal

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use