Promotion

Use code MOM24 for 20% off site wide + free shipping over $45

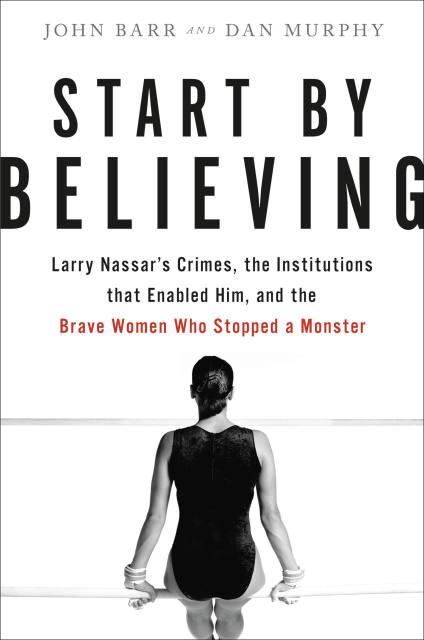

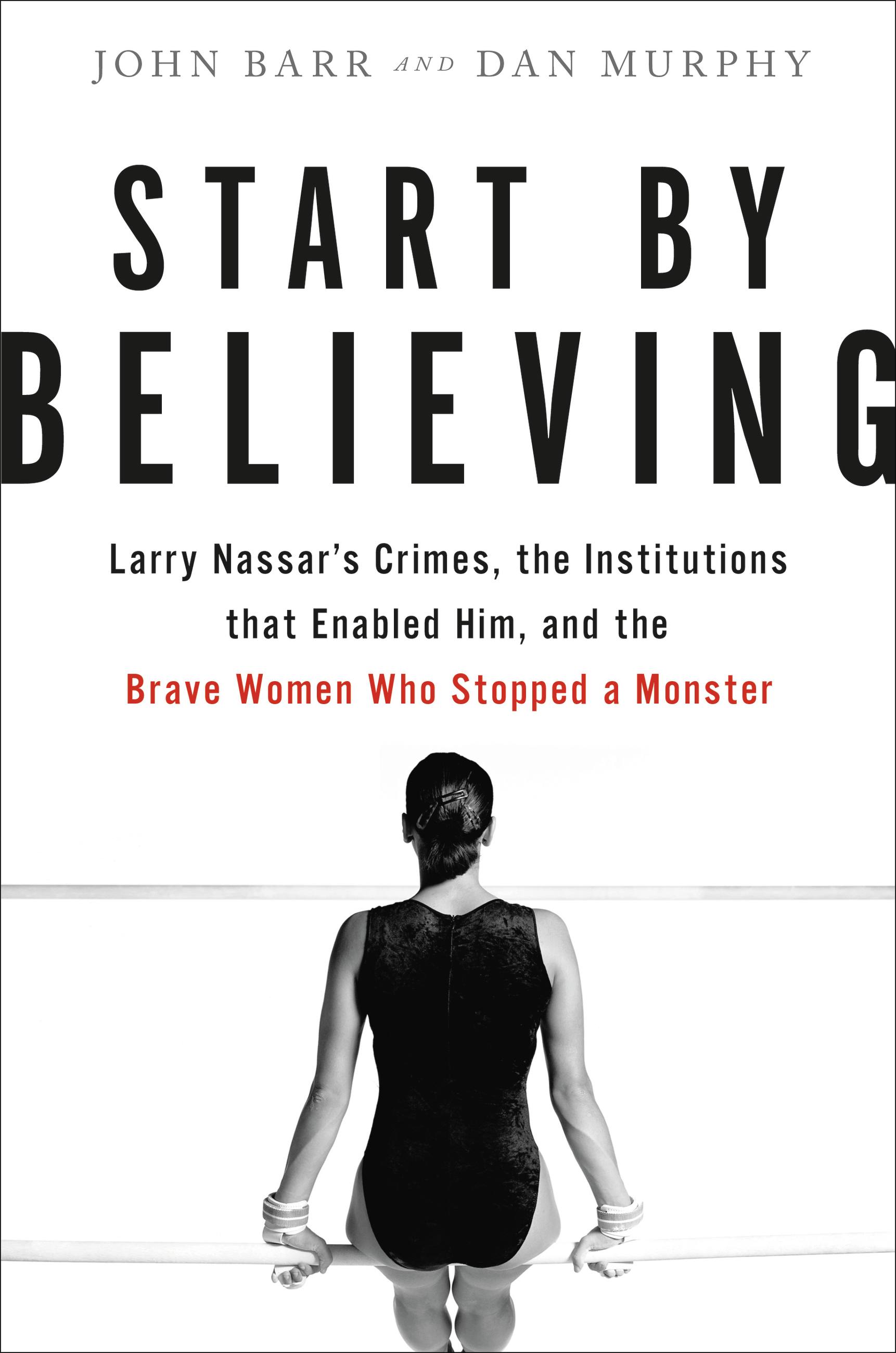

Start by Believing

Larry Nassar's Crimes, the Institutions that Enabled Him, and the Brave Women Who Stopped a Monster

Contributors

By John Barr

By Dan Murphy

Formats and Prices

Price

$14.99Price

$19.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $14.99 $19.99 CAD

- Hardcover $28.00 $35.00 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged)

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around January 14, 2020. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

The definitive, devastating account of the largest sex abuse scandal in American sports history-with new details and insights into the institutional failures, as well as the bravery that brought it to light.

In Start by Believing, John Barr and Dan Murphy confront Nassar’s acts, which represent the largest sex abuse scandal to impact the sporting world. Through never-before-released interviews and documents they deconstruct the epic institutional failures and individuals who enabled him. When warnings were raised, self-serving leaders chose to protect their organizations’ reputations over the well-being of young people.

Following the paths traveled by courageous women-featuring a once-shy Christian attorney and a brash, outspoken Olympic medalist-Barr and Murphy detail the stories of those who fought back against the dysfunction within their sport to claim a far-from-inevitable victory. The gymnasts’ uncommon perseverance, along with the help of dedicated advocates brought criminals to justice and helped to fuel the #MeToo revolution.

Start by Believing reveals the win-at-all-costs culture in elite athletics and higher education that enabled a quarter century of heinous crimes.

Genre:

-

"A taut dramatic narrative, critical new reporting, and a full understanding of how Larry Nassar's unfathomable evil was enabled and given long life. Start by Believing will shock you with its truths, and lift you with the courage of these women."Bob Ley, Emmy Award-winning former host of ESPN's Outside the Lines

-

"This is a horrifying story, and an important one, powerfully and carefully told by journalists John Barr and Dan Murphy. Their meticulously reported narrative presents a riveting account of the courage of these heroic women who will forever define the beginnings of the #MeToo movement."Christine Brennan, bestselling author and USA Today national sports columnist

-

"Thank you John Barr and Dan Murphy for shedding light on the historical account of the crimes of Larry Nassar. This book connects the dots of when and how this atrocity happened, and chronicles the stories of the brave women who eventually acknowledged their truth, found their voice, and fueled a revolution of Time's Up."Valorie Kondos Field, Former UCLA gymnastics coach and seven-time NCAA Champion

-

"A meticulously reported and fearless work, Start by Believing is an epic indictment of the people who for decades enabled the culture of abuse and exploitation that made Larry Nassar's crimes possible, even inevitable. John Barr and Dan Murphy expose the institutional callousness-from coaches to top executives at the USAG-and the price that generations of girls and young women have had to pay."Joan Ryan, bestselling author of Little Girls in Pretty Boxes

-

"Start by Believing is a powerful look at how victims of Larry Nassar's abuse were failed at every step along the way by the institutions-and people-that allowed it to continue unchecked for 25 years. If you want to understand how these unimaginable crimes continued for so long, and what we need to do to ensure that no more young athletes have to face similar dangers, you need to start by reading Start by Believing."Scott Berkowitz, President and Founder of RAINN (Rape, Abuse and Incest National

-

"Not a day goes by when I don't reflect on the survivors of Larry Nassar's horrific crimes. This empathetic, sensitively written book takes a deeper dive into the lives of the people who were hurt and shines a spotlight on their courage. I thank John and Dan for their efforts, which will no doubt support the overall goal of making our beautiful sport safe for athletes once again."Dominique Moceanu, 1996 Olympic Gold Medalist

-

"An incredible story."Cheddar TV

-

"Shocking...enraging."Salon Talks

-

"An important story that needs to be told."PopSugar

-

"[Start By Believing] features reporting so deep, broad, and incisive that it is unlikely to be surpassed...the book is a must-read."Kirkus Reviews (starred review)

-

"[A] hard-hitting expose.... Foregrounding several women who finally brought charges, Barr and Murphy vividly convey the sense of confusion and helplessness that beset victims.... The result is a searing indictment."Publishers Weekly

- On Sale

- Jan 14, 2020

- Page Count

- 352 pages

- Publisher

- Hachette Books

- ISBN-13

- 9780316532136

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use