By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

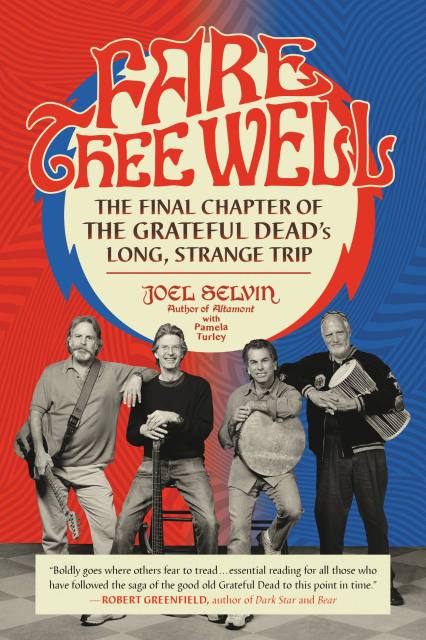

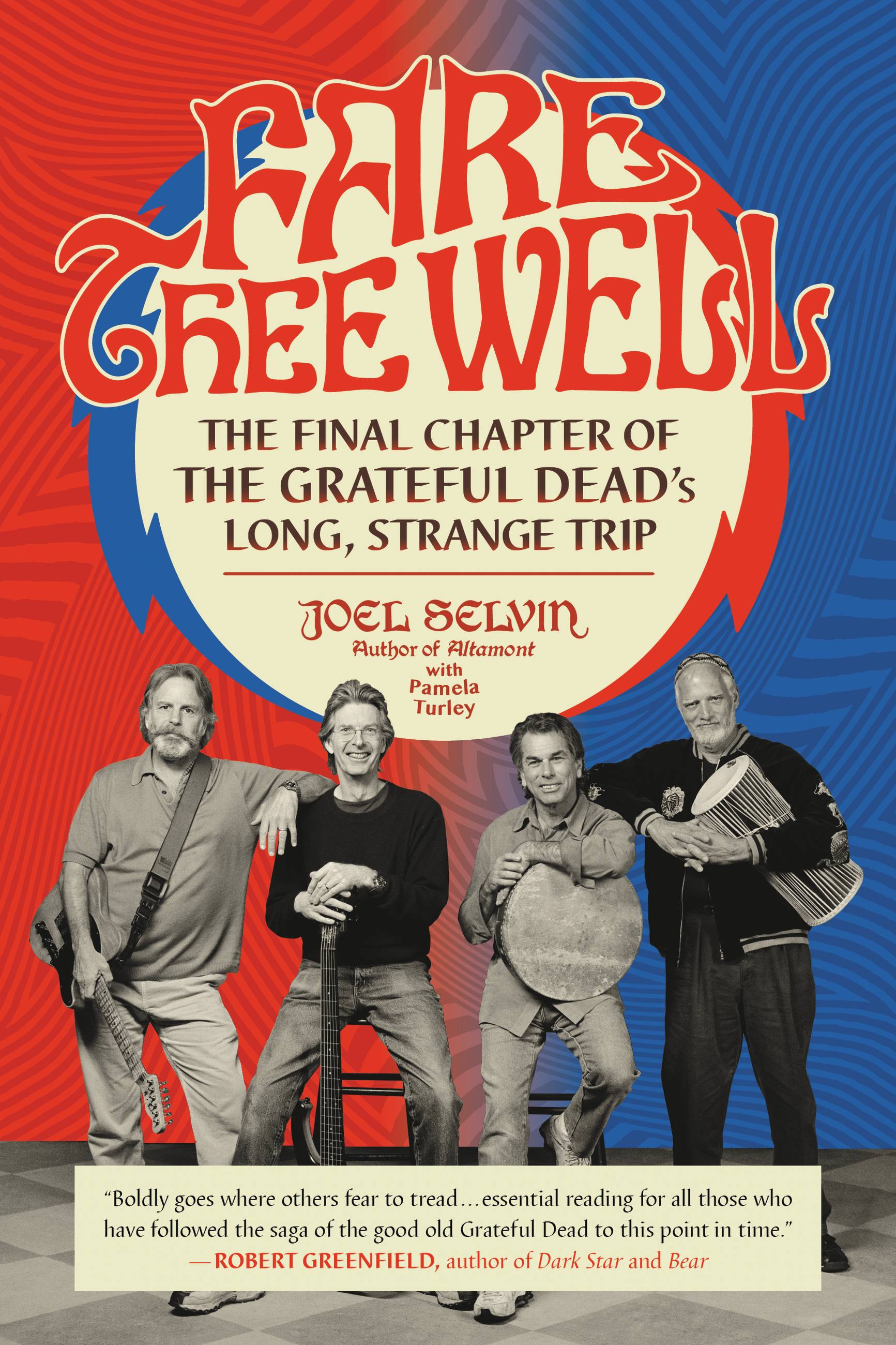

Fare Thee Well

The Final Chapter of the Grateful Dead's Long, Strange Trip

Contributors

By Joel Selvin

With Pamela Turley

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Jun 16, 2020

- Page Count

- 304 pages

- Publisher

- Da Capo

- ISBN-13

- 9780306903069

Price

$19.99Price

$25.99 CADFormat

Format:

- Trade Paperback $19.99 $25.99 CAD

- ebook $17.99 $21.99 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged) $27.99

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around June 16, 2020. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

Genre:

-

"This phenomenon after its leader dies and how and what it became is a great and inspiring story."--Marty Balin, founder of Jefferson Airplane

-

"A deep--and deeply reported--dive into the highs and lows of the Grateful Dead world post-1995, Fare Thee Well is the in-depth postscript we need on life after Garcia. As the surviving members navigate their jarring new world, you'll be shocked, surprised, and unexpectedly moved."--David Browne, author of So Many Roads: The Life and Times of the Grateful Dead

-

"Fare Thee Well is a masterful summation of the agonies, trials, and tribulations that beset the Grateful Dead after Jerry Garcia passed away. It made me sigh with sorrow AND give thanks (virtually simultaneously) for such a gifted group of musicians. This book will appeal to every Deadhead on the planet. I loved it."--Sam Cutler, author of You Can't Always Get What You Want: My Life with the Rolling Stones, the Grateful Dead, and Other Wonderful Reprobates

-

"As always, Joel Selvin boldly goes where others fear to tread. Fare Thee Well is essential reading for all those who have followed the saga of the good old Grateful Dead to this point in time."--Robert Greenfield, author of Dark Star: An Oral Biography of Jerry Garcia and Bear: The Life and Times of Augustus Owsley Stanley III

-

"Fare Thee Well tells the tale of how the Deadheads rescued the Grateful Dead from themselves. Bereft of their heart leader after Jerry Garcia died in 1995, the love of Deadheads kept the music alive so that the phenomena is not merely enduring but growing--long, strange, and still a trip."--Dennis McNally, author of A Long, Strange Trip: The Inside History of the Grateful Dead

-

"I felt like the child of a divorce, but this book showed me I never needed to worry, not when I was under the power of something as great as the Grateful Dead."--Steve Parish, author of Home Before Daylight: My Life on the Road with the Grateful Dead

-

"A hundred years from now, Jerry Garcia may be remembered as a prophet and Bob, Mickey, Phil, and Billy as his disciples. Illuminating, astounding, and accurate, Fare Thee Well is a remarkable account of the successes and failures by the talented, individualist remaining members of the Grateful Dead since the death of their leader Jerry Garcia. I read it in one sitting."--Steve Miller, founder of the Steve Miller Band

-

"Most [Grateful Dead] books end with the 1995 death of Jerry Garcia. Fare Thee Well...takes the opposite approach...[it] examines every sad twist, turn, and betrayal involved in the Dead's various offshoot groups leading up to their 2015 Fare Thee Well reunion."Rolling Stone

-

"An unblinking and balanced look at the infighting, backbiting, rancor and resentments among the surviving 'core four' band members."Paul Liberatore, Marin Independent Journal

-

"An enthusiastic but clear-eyed and enjoyably gossipy piece of modern rock history."Publishers Weekly

-

"[Fare Thee Well] engages readers intrigued by the Dead's mystique. For Deadheads, sure, but also rock fans who may wonder where the road led after Jerry died."Kirkus

-

"Well-written...[Selvin] has covered the Dead nearly since their inception and did extensive research and interviewing for this book."Library Journal

-

"Selvin's history of the resurrection of the band after Garcia's death is at the same time a sad and (somewhat) heartening story."Vintage Guitar

-

"Fare Thee Well is by turns sad, surprising, and uplifting, and a crucial addition to any Bookshelf of the Dead."Houston Press

-

"Fare Thee Well tells Classic Rock's film noir story."Daily Beast

-

"Selvin smartly steers clear of tie-dyed '60s mysticism, offering instead a reported look at the lives of the remaining "core four" members. It is a breezy history, not only of the many incarnations of Dead bands that popped up, but also of how the four men grappled with their own ambitions."Washington Post

-

"Fare Thee Well is a detailed look at the post-Garcia careers of all remaining Dead members, rendered in engaging, storytelling fashion."Under the Radar

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use