Promotion

Use code SPRING26 for 20% off sitewide.

By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

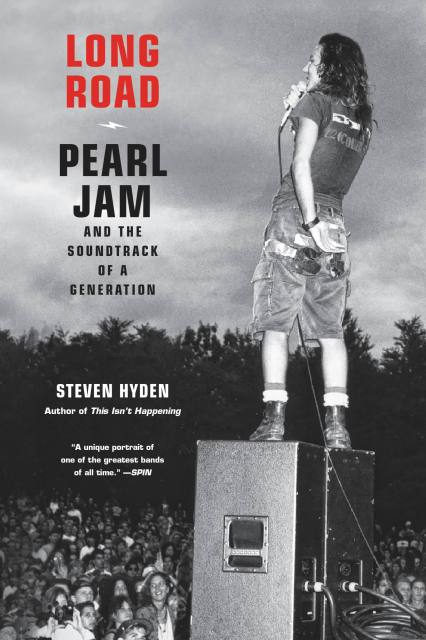

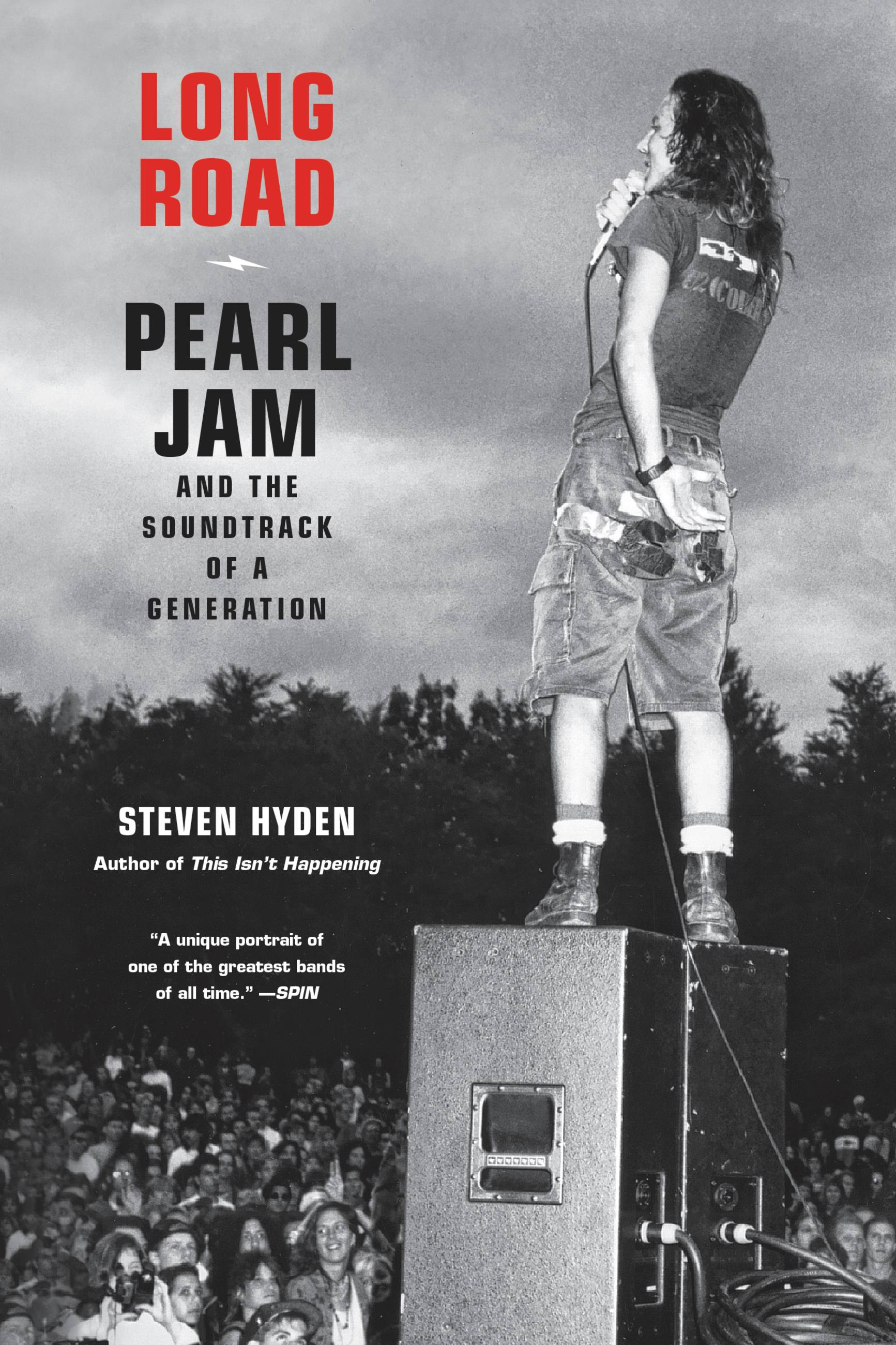

Long Road

Pearl Jam and the Soundtrack of a Generation

Contributors

By Steven Hyden

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Oct 10, 2023

- Page Count

- 272 pages

- Publisher

- Da Capo

- ISBN-13

- 9780306826436

Price

$19.99Price

$25.99 CADFormat

Format:

- Trade Paperback $19.99 $25.99 CAD

- ebook $15.99 $20.99 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged) $24.99

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around October 10, 2023. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

A leading music journalist’s riveting chronicle of how beloved band Pearl Jam shaped the times, and how their legacy and longevity have transcended generations.

Ever since Pearl Jam first blasted onto the Seattle grunge scene three decades ago with their debut album, Ten, they have sold 85M+ albums, performed for hundreds of thousands of fans around the world, and have even been inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame. In Long Road: Pearl Jam and the Soundtrack Of A Generation, music critic and journalist Steven Hyden celebrates the life, career, and music of this legendary group, widely considered to be one of the greatest American rock bands of all time. Long Road is structured like a mix tape, using 18 different Pearl Jam classics as starting points for telling a mix of personal and universal stories. Each chapter tells the tale of this great band — how they got to where they are, what drove them to greatness, and why it matters now.Much like the generation it emerged from, Pearl Jam is a mass of contradictions. They were an enormously successful mainstream rock band who felt deeply uncomfortable with the pursuit of capitalistic spoils. They were progressive activists who spoke in favor of abortion rights and against the Ticketmaster monopoly, and yet they epitomized the sound of traditional, male-dominated rock ‘n’ roll. They were looked at as spokesmen for their generation, even though they ultimately projected profound confusion and alienation. They triumphed, and failed, in equal doses — the quintessential Gen-X tale.

Impressive as their stats, accolades, and longevity may be, Hyden also argues that Pearl Jam’s most definitive accomplishment lies in the impact their music had on Generation X as a whole. Pearl Jam’s music helped an entire generation of listeners connect with the glory of bygone rock mythology, and made it relevant during a period in which tremendous American economic prosperity belied a darkness at the heart of American youth. More than just a chronicle of the band’s career, this book is also a story about Gen- X itself, who like Pearl Jam came from angsty, outspoken roots and then evolved into an establishment institution, without ever fully shaking off their uncertain, outsider past. For so many Gen-Xers growing up at the time, Pearl Jam’s music was a beacon that offered both solace and guidance. They taught an entire generation how to grow up without losing the purest and most essential parts of themselves.

Written with his celebrated blend of personal memoir, criticism, and journalism, Hyden explores Pearl Jam’s path from Ten to now. It’s a chance for new fans and old fans alike to geek out over Pearl Jam minutia—the B-sides, the beloved deep cuts, the concert bootlegs—and explore the multitude of reasons why Pearl Jam’s music resonated with so many people. As Hyden explains, “Most songs pass through our lives and are swiftly forgotten. But Pearl Jam is forever.”

Genre:

-

**Rolling Stone, "Best Music Books of 2022"**

**Corbin Reiff at SPIN, "Best Rock Biography of the Year (2022)"**

Aquarian, "Holiday Guide for the Rock & Roll Literate* -

“Steven Hyden is a brilliant rock chronicler, whether he’s writing about great bands or terrible ones. But with LONG ROAD, as Eddie Vedder would say, he’s unleashed a lion.”Rolling Stone

-

"[The] best rock biography [of 2022]... Steven Hyden has all the answers [to Pearl Jam] and delivers them with the kind of wittily insightful analysis you only get from an obsessed fan and expert critic.”Corbin Reiff, SPIN

-

“A comprehensive look from the perspective of a devoted (if not sometimes concerned) fan, this book is organized like Hyden’s favorite Pearl Jam mixtape, into chapters corresponding to a specific song and then elaborating from there, taking the reader to many fascinating, surprising places that aren’t well-known about the Seattle icons."SPIN

-

"[Long Road is]... clear-eyed about Pearl Jam’s strengths and weaknesses, but also quite personal, the author infusing his own memories of coming of age at a time when Vs. and Vitalogy provided the soundtrack. The book wrestles with the question of why Pearl Jam mattered — and why, to some, they still very much do.”Inside Hook

-

“In LONG ROAD, [Steven] Hyden gives almost an autobiographical history of Pearl Jam from the fan's perspective, from the early albums, to their shying away from the spotlight, through their embrace of playing unforgettable live shows in front of their increasingly fanatical fanbase.”AllMusic

-

“Must-read… There is no one writing about music with more passion and intellect than Steven Hyden."The Film Stage

-

“Through smart but accessible writing full of stories, asides, opinions and analysis, Hyden makes a compelling case for why Pearl Jam’s music matters….A joyous, thought-provoking and humane series of essays.”Pittsburgh Post-Gazette

-

"A personal approach and valuable critical companion that does a great job of contextualizing the band's various life cycles."Wisconsin Public Radio

-

“One of the most entertaining summations of what a rock band can do to one’s soul whether we like to admit it or not.”Aquarian

-

“Reading Long Road feels as if you’re in an endlessly engrossing conversation about Pearl Jam with a fellow admirer.”Toronto Star

-

"[Hyden has] penned a thoroughly compelling book about Pearl Jam.”Q101

-

"A critical consideration of one of rock’s most durable and inscrutable acts... A music biography well suited to fans of both the band and 1990s pop culture."Kirkus

-

"Steven Hyden’s Long Road takes us well beyond the Pearl Jam story that has been rehashed for decades. He argues that the most commercially successful band of the alt-rock era is fundamentally misunderstood, and then he backs up that assertion with chapter after chapter packed with insights and fresh context. In this rock bio-as-mixtape configuration, the prose is as much impressionistic as linear, a format that suits a band that has figured out how to reinvent and improvise its way to hard-earned longevity."Greg Kot, Sound Opinions co-host

-

“As a die-hard and nearly life-long Pearl Jam fan, I cannot recommend Long Road enough. It is an essential perspective on one of the world’s greatest bands with incredibly heartfelt insight from Steven Hyden.”Brian Fallon of The Gaslight Anthem