By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

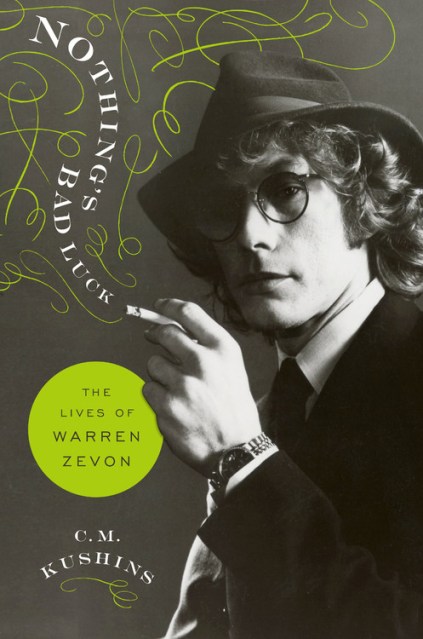

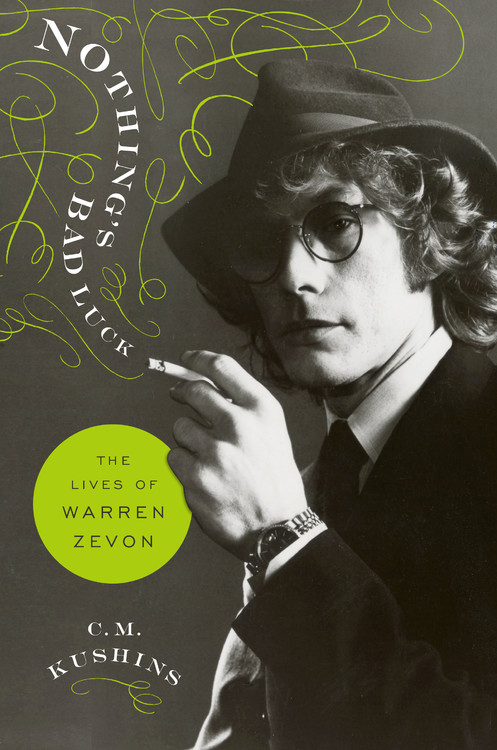

Nothing’s Bad Luck

The Lives of Warren Zevon

Contributors

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- May 7, 2019

- Page Count

- 416 pages

- Publisher

- Da Capo

- ISBN-13

- 9780306921483

Price

$29.00Price

$38.00 CADFormat

Format:

- Hardcover $29.00 $38.00 CAD

- ebook $14.99 $19.99 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged)

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around May 7, 2019. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

Biography of legendary singer-songwriter Warren Zevon, spanning his nomadic youth and early recording career to his substance abuse, final album, and posthumous Grammy Awards

As is the case with so many musicians, the life of Warren Zevon was blessed with talent and opportunity yet also beset by tragedy and setbacks. Raised mostly by his mother with an occasional cameo from his gangster father, Warren had an affinity and talent for music at an early age. Taking to the piano and guitar almost instantly, he began imitating and soon creating songs at every opportunity. After an impromptu performance in the right place at the right time, a record deal landed on the lap of a teenager who was eager to set out on his own and make a name for himself. But of course, where fame is concerned, things are never quite so simple.

Drawing on original interviews with those closest to Zevon, including Crystal Zevon, Jackson Browne, Mitch Albom, Danny Goldberg, Barney Hoskyns, and Merle Ginsberg, Nothing’s Bad Luck tells the story of one of rock’s greatest talents. Journalist C.M. Kushins not only examines Zevon’s troubled personal life and sophisticated, ever-changing musical style, but emphasizes the moments in which the two are inseparable, and ultimately paints Zevon as a hot-headed, literary, compelling, musical genius worthy of the same tier as that of Bob Dylan and Neil Young.

In Nothing’s Bad Luck, Kushins at last gives Warren Zevon the serious, in-depth biographical treatment he deserves, making the life of this complex subject accessible to fans old and new for the very first time.

As is the case with so many musicians, the life of Warren Zevon was blessed with talent and opportunity yet also beset by tragedy and setbacks. Raised mostly by his mother with an occasional cameo from his gangster father, Warren had an affinity and talent for music at an early age. Taking to the piano and guitar almost instantly, he began imitating and soon creating songs at every opportunity. After an impromptu performance in the right place at the right time, a record deal landed on the lap of a teenager who was eager to set out on his own and make a name for himself. But of course, where fame is concerned, things are never quite so simple.

Drawing on original interviews with those closest to Zevon, including Crystal Zevon, Jackson Browne, Mitch Albom, Danny Goldberg, Barney Hoskyns, and Merle Ginsberg, Nothing’s Bad Luck tells the story of one of rock’s greatest talents. Journalist C.M. Kushins not only examines Zevon’s troubled personal life and sophisticated, ever-changing musical style, but emphasizes the moments in which the two are inseparable, and ultimately paints Zevon as a hot-headed, literary, compelling, musical genius worthy of the same tier as that of Bob Dylan and Neil Young.

In Nothing’s Bad Luck, Kushins at last gives Warren Zevon the serious, in-depth biographical treatment he deserves, making the life of this complex subject accessible to fans old and new for the very first time.

Genre:

-

"Nothing's Bad Luck is a riveting, definitive, and exhaustive account of the suspenseful and eventful life of one of rock's most gifted and eccentric singer-songwriters, and one of the best rock and roll biographies of the past decade."Jay McInerney, author of Bright, Precious Days and Bright Lights, Big City

-

Amazon, "Best Books of the Month in Biographies and Memoirs"

Amazon, "Best Books of the Year So Far in Humor and Entertainment" -

"The best of the books written thus far about Warren Zevon is Nothing's Bad Luck. C.M. Kushins follows the legendary singer/songwriter down streets mostly Californian and mean; like a good detective, he sifts through the relationships and songs left behind. What he uncovers makes for compelling reading."Kevin Avery, author of Everything Is an Afterthought: The Life and Writings of Paul Nelson

-

"Kushins's energetic writing and his deep dive into Zevon's life and music offers a rounded and complete portrait of an enigmatic musician."Publishers Weekly, starred review

-

"This book will have you pulling out records, or launching your streaming app of choice, and digging into Zevon's exceptional catalog."Brooklyn Rail

-

"[A] deep, rewarding and insightful biography... an embarrassment of riches on the Excitable Boy, Mr. Bad Example, and a howling L.A. werewolf."The Houston Press

-

"[A] straightforward account, including a comprehensive discography, of Zevon's fascinating creative life."Booklist

-

"Chad Kushins has delivered a nuanced, in-depth, loving look at this complicated figure, one that helps cement him as one of the most complex and captivating musicians of our times."NPR.org

-

"[An] absorbing, compelling biography."Shelf Awareness

-

"[An] appreciative but honest biography."Milwaukee Journal-Sentinel

-

"[Kushins] captures the essence of the brooding yet wickedly witty singer."Booklist

-

"[Chad Kushins is] articulate and authoritative in recounting [Zevon's life] precisely because he knows his subject inside out."All about Jazz

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use