By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

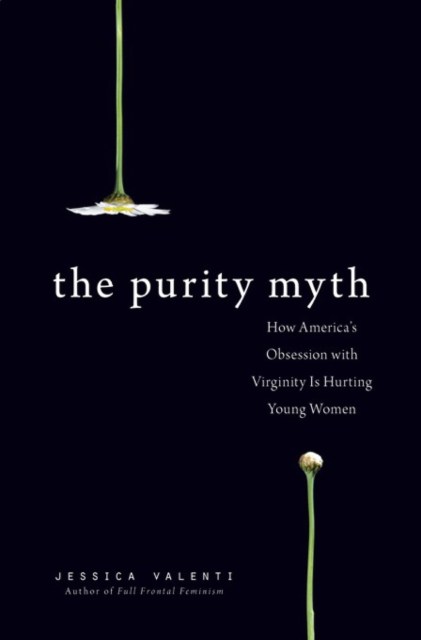

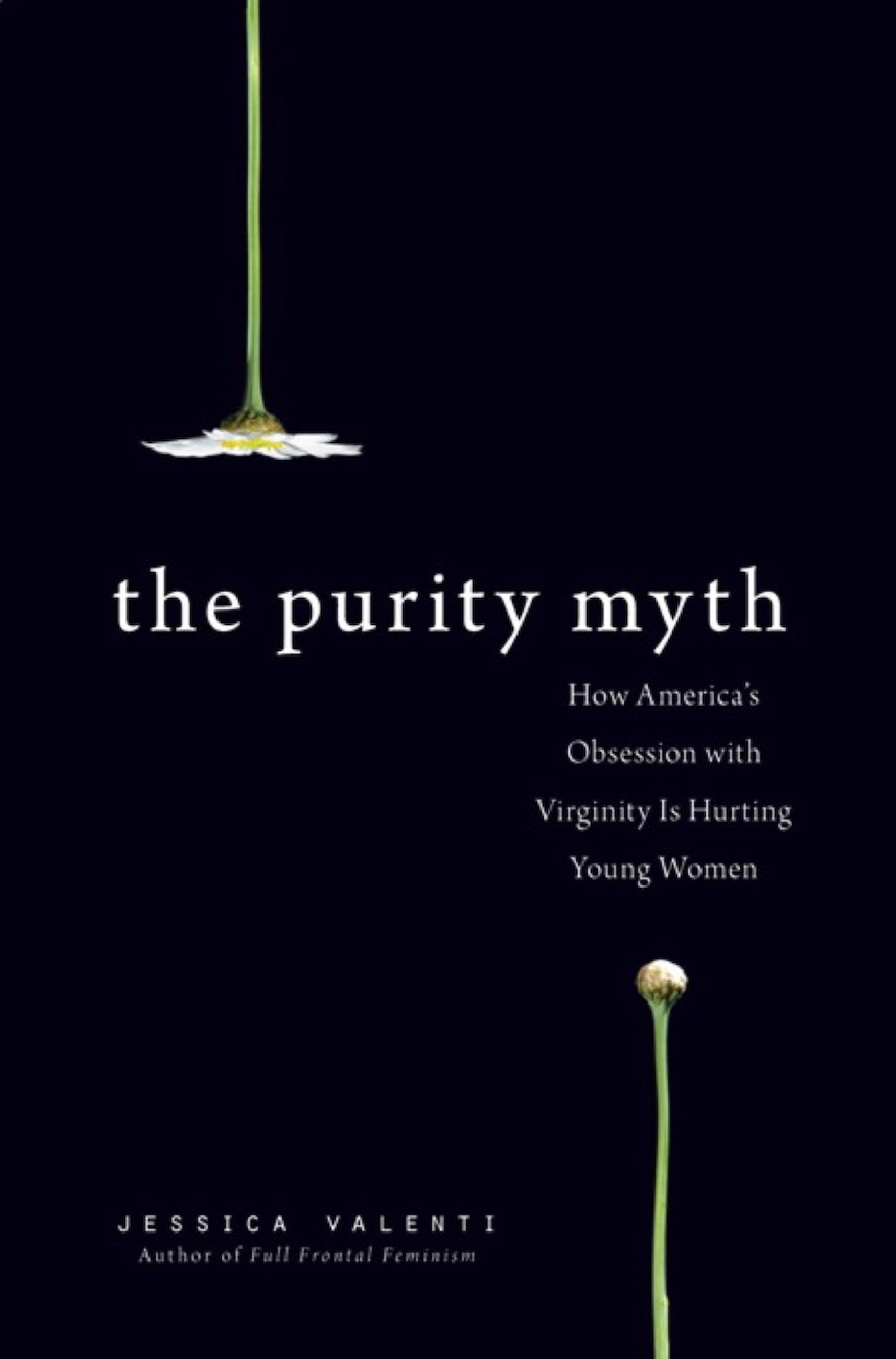

The Purity Myth

How America's Obsession with Virginity Is Hurting Young Women

Contributors

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Mar 24, 2009

- Page Count

- 300 pages

- Publisher

- Seal Press

- ISBN-13

- 9780786744664

Price

$11.99Price

$14.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $11.99 $14.99 CAD

- Trade Paperback $18.99 $24.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around March 24, 2009. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

From the bestselling author of Sex Object, a searing investigation into American culture’s obsession with virginity, and the argument for creating a future where women and girls are valued for more than sexuality

The United States is obsessed with virginity–from the media to schools to government agencies. In The Purity Myth, Jessica Valenti argues that the country’s intense focus on chastity is damaging to young women. Through in-depth cultural and social analysis, Valenti reveals that powerful messaging on both extremes–ranging from abstinence-only curriculum to “Girls Gone Wild” infomercials–place a young woman’s worth entirely on her sexuality. Morals are therefore linked purely to sexual behavior, rather than values like honesty, kindness, and altruism. Valenti sheds light on the value–and hypocrisy–around the notion that girls remain virgins until they’re married by putting into context the historical question of purity, modern abstinence-only education, pornography, and public punishments for those who dare to have sex. The Purity Myth presents a revolutionary argument that girls and women are overly valued for their sexuality, as well as solutions for a future without a damaging emphasis on virginity.

The United States is obsessed with virginity–from the media to schools to government agencies. In The Purity Myth, Jessica Valenti argues that the country’s intense focus on chastity is damaging to young women. Through in-depth cultural and social analysis, Valenti reveals that powerful messaging on both extremes–ranging from abstinence-only curriculum to “Girls Gone Wild” infomercials–place a young woman’s worth entirely on her sexuality. Morals are therefore linked purely to sexual behavior, rather than values like honesty, kindness, and altruism. Valenti sheds light on the value–and hypocrisy–around the notion that girls remain virgins until they’re married by putting into context the historical question of purity, modern abstinence-only education, pornography, and public punishments for those who dare to have sex. The Purity Myth presents a revolutionary argument that girls and women are overly valued for their sexuality, as well as solutions for a future without a damaging emphasis on virginity.

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use