By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

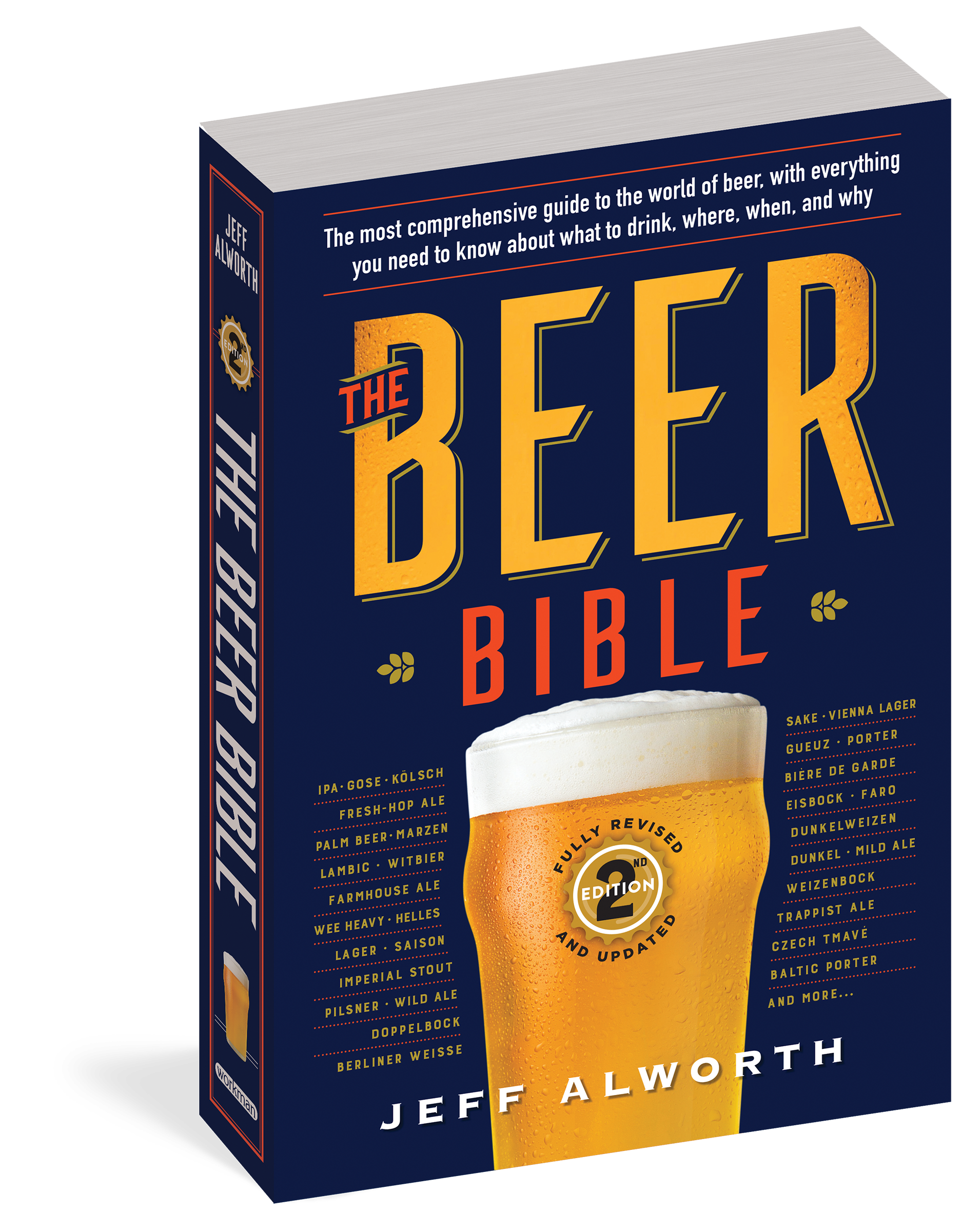

The Beer Bible: Second Edition

Contributors

By Jeff Alworth

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Sep 28, 2021

- Page Count

- 656 pages

- Publisher

- Workman Publishing Company

- ISBN-13

- 9781523510450

Price

$24.99Price

$32.99 CADFormat

Format:

- Trade Paperback (Revised) $24.99 $32.99 CAD

- ebook $12.99 $16.99 CAD

- Hardcover (Revised) $37.50 $47.50 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around September 28, 2021. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

“The ultimate guide.” —Sports Illustrated

Imagine sitting in your favorite pub with a good friend who just happens to have won a TACP Award—a major culinary accolade—for writing the book about beer. Then imagine that he’s been spending the years following the first edition exploring all the changes that continue to shape and evolve the brewing world. That’s this book, the completely revised and updated bible on beer that covers everything: The History, or how we got from the birth of malting and national traditions to a hazy IPA in 12,000 years. The Variety: dozens of styles and hundreds of brews, along with recommended “Beers to Know.” The Curiosity: If beer’s your passion, you’ll delight in learning what type of hops went into a favorite beer and where to go for beer tourism, as well as profiles of breweries from around the world. And lastly, The Pleasure. Because, ultimately, that’s what it’s all about.

“A tome worthy of its name.” —Food and Wine

“Easily digestible for drinkers of all levels.”—Imbibe

“Pick up this book as a refresher or a gift, lest we forget that spreading beer education is just as important as advocating for good beer itself.”—Beer Advocate

Series:

-

Praise for the first edition:

"The only book you need to understand the world’s most popular beverage.” – John Holl, All About Beer Magazine

“… a box of treats… It’s a delight to find a book about beer that covers the subject in such breadth and depth at the same time as making it seem fresh and new again” – Pete Brown, All About Beer

“A must-read.” – Craft Beer Brewing

“Jeff Alworth has an impressive track record as a leading exponent of the global craft beer movement… this tome will educate and leave you thirsty for a cold one” – Book Page

“a tome worthy of its name” – Food+Wine.com

“Beer enthusiasts will welcome this guide that feels like one is spending time with a well-versed drinking pal” – Library Journal

“The Beer Bible endows beer lovers with the same incredible depth and scope of information that Karen MacNeil’s The Wine Bible gave to enophiles” – Tasting Panel Magazine

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use