Promotion

Use code SPRING26 for 20% off sitewide.

By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

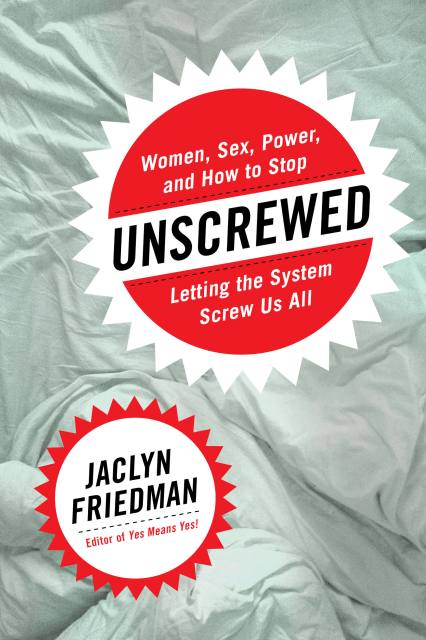

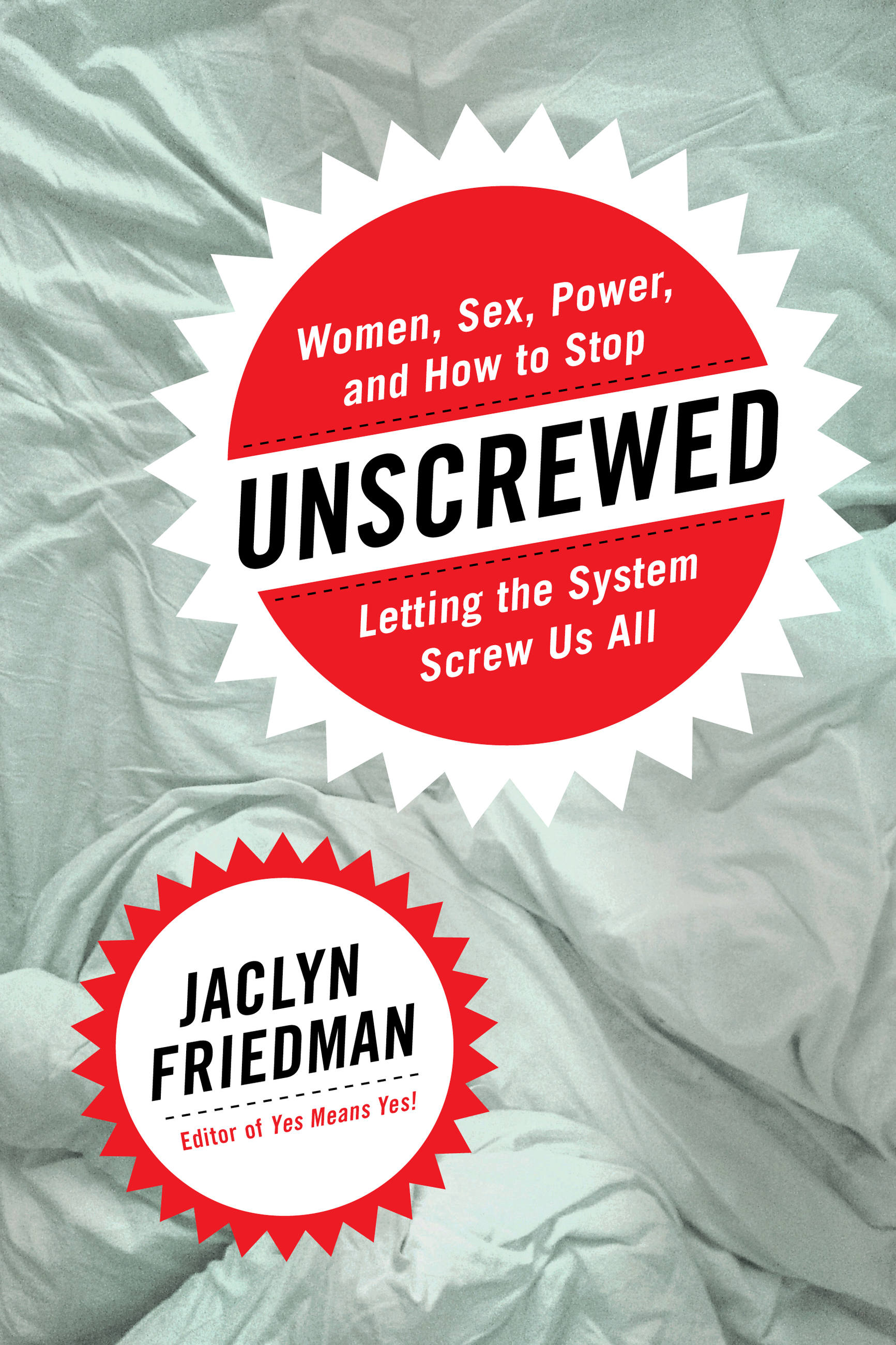

Unscrewed

Women, Sex, Power, and How to Stop Letting the System Screw Us All

Contributors

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Nov 14, 2017

- Page Count

- 288 pages

- Publisher

- Seal Press

- ISBN-13

- 9781580056427

Price

$17.99Price

$22.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $17.99 $22.99 CAD

- Hardcover $37.00 $47.00 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged)

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around November 14, 2017. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

As a veteran feminist and agenda-setting sex educator, Jaclyn Friedman is on the frontlines of the war for equity between the sexes. In Unscrewed, Friedman brings her sharp expertise and incisive observations on the state of sexual politics to the fore, sparking a culture-wide rethink about sex, power and what we accept.

With reportage and verve, Unscrewed builds a searing investigation into the state of sexual power in America, and outlines how to make real progress toward equality. Friedman reveals that the anxiety and fear women in our country feel around issues of their sexuality are not, in fact, their fault, but instead are side effects of what she calls our “era of fauxpowerment,” wherein women have the illusion of sexual power, with no actual power to support it. Exploring the fault lines where media, religion, politics, and education impinge on our intimate lives, Unscrewed breaks down the causes and signs of fauxpowerment, then gives readers tools to take it on themselves.