Promotion

Use code MOM24 for 20% off site wide + free shipping over $45

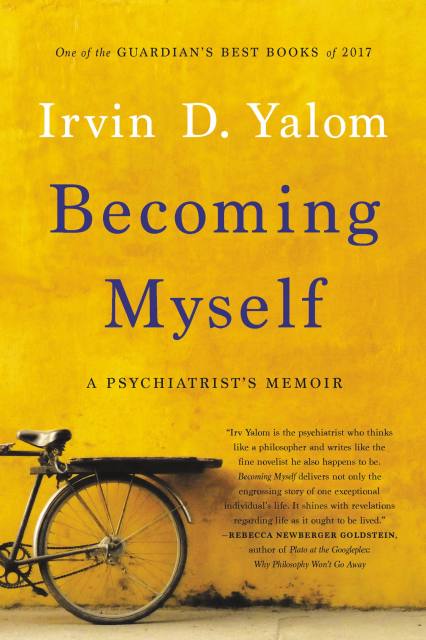

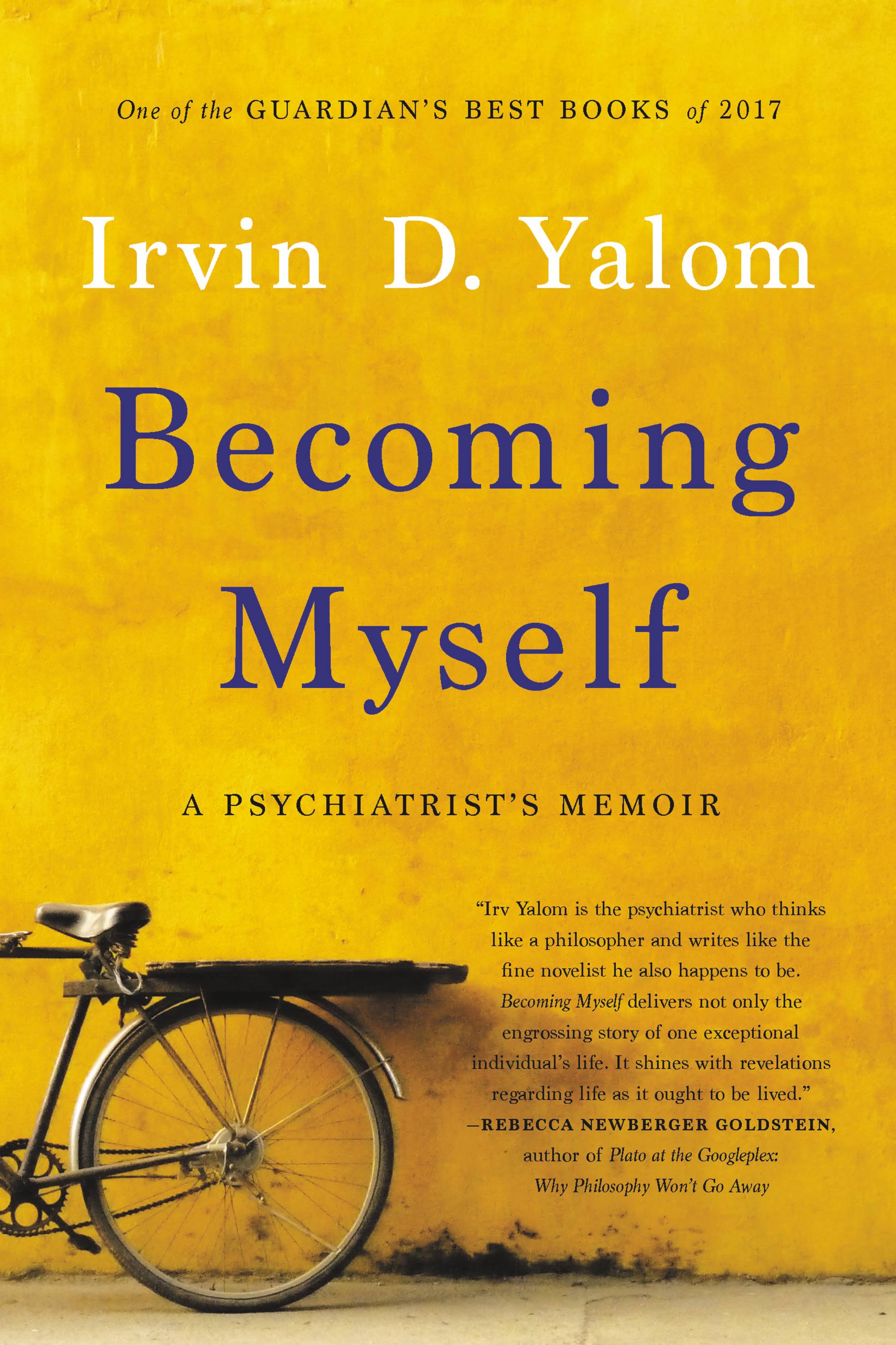

Becoming Myself

A Psychiatrist's Memoir

Contributors

Formats and Prices

Price

$12.99Price

$16.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $12.99 $16.99 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged)

- Trade Paperback $19.99 $24.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around October 3, 2017. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

Irvin D. Yalom has made a career of investigating the lives of others. In this profound memoir, he turns his writing and his therapeutic eye on himself. He opens his story with a nightmare: He is twelve, and is riding his bike past the home of an acne-scarred girl. Like every morning, he calls out, hoping to befriend her, "Hello Measles!" But in his dream, the girl's father makes Yalom understand that his daily greeting had hurt her. For Yalom, this was the birth of empathy; he would not forget the lesson. As Becoming Myself unfolds, we see the birth of the insightful thinker whose books have been a beacon to so many. This is not simply a man's life story, Yalom's reflections on his life and development are an invitation for us to reflect on the origins of our own selves and the meanings of our lives.

Genre:

- On Sale

- Oct 3, 2017

- Page Count

- 352 pages

- Publisher

- Basic Books

- ISBN-13

- 9780465098903

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use