By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

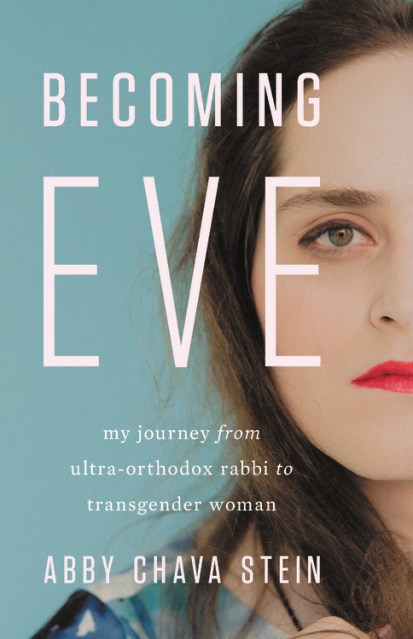

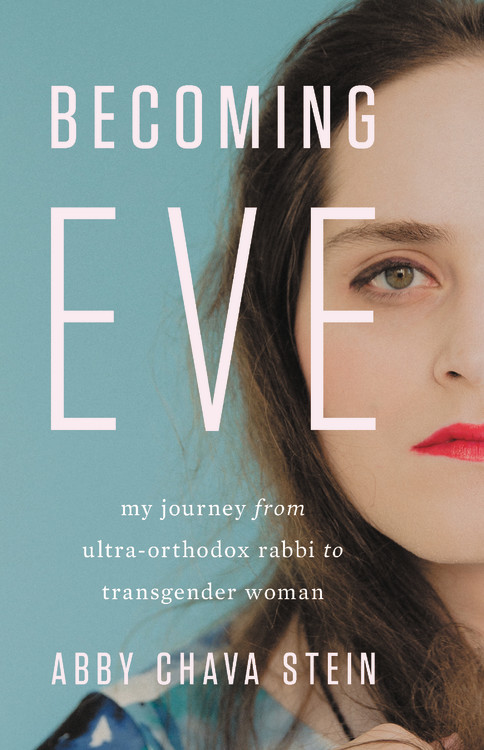

Becoming Eve

My Journey from Ultra-Orthodox Rabbi to Transgender Woman

Contributors

By Abby Stein

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Nov 12, 2019

- Page Count

- 272 pages

- Publisher

- Seal Press

- ISBN-13

- 9781580059169

Price

$30.00Price

$40.00 CADFormat

Format:

- Hardcover $30.00 $40.00 CAD

- ebook $17.99 $22.99 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged)

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around November 12, 2019. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

The powerful coming-of-age story of an ultra-Orthodox child who was born to become a rabbinic leader and instead became a woman

Abby Stein was raised in a Hasidic Jewish community in Brooklyn, isolated in a culture that lives according to the laws and practices of eighteenth-century Eastern Europe, speaking only Yiddish and Hebrew and shunning modern life. Stein was born as the first son in a dynastic rabbinical family, poised to become a leader of the next generation of Hasidic Jews.

But Abby felt certain at a young age that she was a girl. She suppressed her desire for a new body while looking for answers wherever she could find them, from forbidden religious texts to smuggled secular examinations of faith. Finally, she orchestrated a personal exodus from ultra-Orthodox manhood to mainstream femininity-a radical choice that forced her to leave her home, her family, her way of life.

Powerful in the truths it reveals about biology, culture, faith, and identity, Becoming Eve poses the enduring question: How far will you go to become the person you were meant to be?

Abby Stein was raised in a Hasidic Jewish community in Brooklyn, isolated in a culture that lives according to the laws and practices of eighteenth-century Eastern Europe, speaking only Yiddish and Hebrew and shunning modern life. Stein was born as the first son in a dynastic rabbinical family, poised to become a leader of the next generation of Hasidic Jews.

But Abby felt certain at a young age that she was a girl. She suppressed her desire for a new body while looking for answers wherever she could find them, from forbidden religious texts to smuggled secular examinations of faith. Finally, she orchestrated a personal exodus from ultra-Orthodox manhood to mainstream femininity-a radical choice that forced her to leave her home, her family, her way of life.

Powerful in the truths it reveals about biology, culture, faith, and identity, Becoming Eve poses the enduring question: How far will you go to become the person you were meant to be?

-

"Becoming Eve is a powerful, heartfelt account of the often fraught journey toward one's true self. In sharing her story, Abby Chava Stein lights the path for all of us who are embarking on journeys of our own."TOVA MIRVIS, bestselling author of The Book of Separation, The Ladies Auxiliary, and The Outside World

-

"Becoming Eve is a beautiful, haunting story of self-discovery. Her longing for truth, acceptance, and love will echo in the heart of every reader."LEAH VINCENT, author of Cut Me Loose: Sin and Salvation After My Ultra-Orthodox Girlhood

-

"Becoming Eve is a powerful, moving story of grappling with both gender and faith. Abby Chava Stein is a compelling storyteller who shows us how to follow the voice within--even when everyone and everything around us is telling us not to."DANYA RUTTENBERG, author of Surprised By God and Nurture the Wow

-

"'No agenda, just my story,' Abby Stein writes in the prologue to her fascinating memoir. And yet, her book delivers on a very definite agenda: helping us empathize with experiences radically different from our own. With humor and grace-and impressive erudition of Jewish mysticism-Abby Stein grants us entry into a singular, otherworldly capsule: the byzantine world of Hasidic 'royal' families and the Sisyphean pursuit of living an authentic life within it.SHULEM DEEN, author of All Who Go Do Not Return, winner of the Prix Médicis and the National Jewish Book Award

-

"Abby Stein's soul-searching memoir grabbed me at the epigraph and never let me go. While religion is certainly a central element in the story, Becoming Eve is just as importantly about a different sense of faith: a belief in life's transformative potential to culminate in joy."SUSAN STRYKER, professor of gender and women's studies, Emmy Award-winning filmmaker, and author of Transgender History: The Roots of Today's Revolution

-

"Becoming Eve is a vivid journey through Abby Stein's formative years in the Ultra-Orthodox Hasidic Jewish community as she struggles to find a more inclusive expression of her faith and learns to embrace her identity as a woman of trans experience."SARAH VALENTINE, author of When I Was White

-

"Not only is Abby a trailblazer and ridiculously inspiring--she's a really talented writer. Becoming Eve is not to be missed."Alma.com

-

"The harrowing and inspiring story of the exploration, discovery, and acceptance of her truth, both body and soul."Publishers Weekly

-

"Born into an ultra-Orthodox Jewish family, it was always expected that Abby Stein would become a leader in the Hasidic community. But Abby, born a male, knew at a very young age that she identified as a woman. Eventually, she broke free of her community's and family's expectations to become the person she wanted to be."Parade, ?Memoirs You Need to Be Reading Now?

-

"A transgender woman recounts her evolution from a male-born child in the ultra-Orthodox Hasidic Jewish community to a thriving independent activist in this coming-of-age memoir."Kirkus

-

"A valuable addition to the body of transgender literature."Booklist

-

"The book gives readers a frank look at what it was like to come of age misgendered in one of the world's most gender-segregated societies. More so, it's about Stein becoming the woman she is and about her finally being able to embrace Judaism on her terms."Times of Israel

-

"A frank account of an exceptional life. Stein is a gifted writer, full of grace and compassion."Jewish Journal