Promotion

Use code SPRING26 for 20% off sitewide.

By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

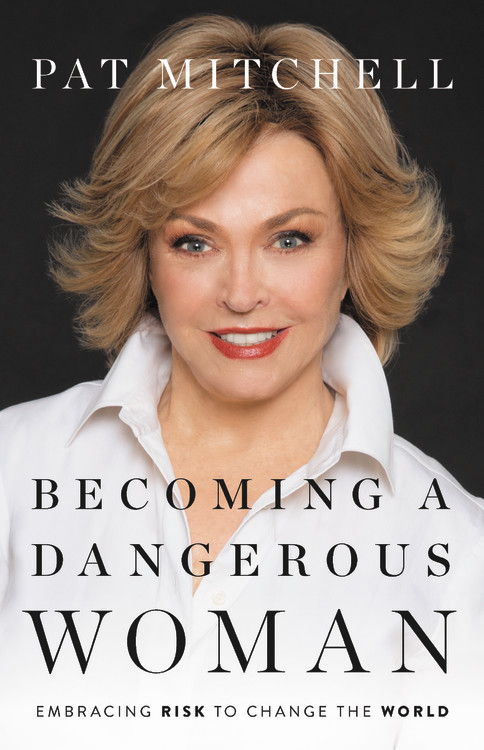

Becoming a Dangerous Woman

Embracing Risk to Change the World

Contributors

By Pat Mitchell

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Oct 8, 2019

- Page Count

- 304 pages

- Publisher

- Seal Press

- ISBN-13

- 9781580059299

Price

$28.00Price

$35.00 CADFormat

Format:

- Hardcover $28.00 $35.00 CAD

- ebook $17.99 $22.99 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged)

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around October 8, 2019. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

An intimate and inspiring memoir and call to action from Pat Mitchell — groundbreaking media icon, global advocate for women’s rights, and co-founder and curator of TEDWomen

Pat Mitchell is a serial ceiling smasher. The first woman to own and host a nationally syndicated daily talk show, and the first female president of CNN productions and PBS, Mitchell has been lauded as a powerful changemaker and a relentless advocate for women and girls.

In Becoming a Dangerous Woman, Mitchell shares her own path to power, from a childhood spent on a cotton farm in the South to her unprecedented rise in media and global affairs. Full of intimate, fascinating stories, such as an encounter with Fidel Castro while wearing a swimsuit, and traveling to war zones with Eve Ensler and Glenn, Becoming a Dangerous Woman is an inspiring call to arms for women who are ready to dismantle the barriers they see in their own lives.

-

Named one of the "Most Powerful Women in Hollywood" by Hollywood Reporter

-

"Becoming a Dangerous Woman illuminates the paths strong leaders take to tackle challenges and gain wisdom. By curating and amplifying the voices of women who have defied categorization, Pat Mitchell delivers a work that will encourage other women to find their dangerous sides."Stacey Abrams

-

"For decades, Pat Mitchell has been on the media frontlines as an uncompromising force for good. She has used her platform to document injustices in a societal system plagued by sexism, racism, and economic inequalities. To the powers that be who are allowing human rights abuses to be exploited and overlooked, Pat Mitchell is a very dangerous woman indeed. Pat Mitchell makes being a dangerous woman a badge of honor, one that should be worn with pride."Thandie Newton

-

"Pat has been the connector, the spark plug, and the strategist behind more important women's events and forums than seems possible."Jane Fonda

-

"Pat is that most rare of leaders, one who is trusted by the decision makers as they now exist, and also by the future decision makers hoping to expand what exists."Gloria Steinem

-

"I've witnessed what a force of nature Pat Mitchell becomes when she believes in something. And, fortunately for all of us, she believes in making our world better. As a passionate advocate, producer, and mentor, her commitment to empowering and inspiring women and girls through telling their stories is changing hearts and minds. I am glad to both know and work with her, and to watch her impact grow."Robert Redford

-

"I can think of no woman who does more to move other women forward. From creating and providing platforms for women to share their voices, to making sure women are hired on the job, to insisting women are front and center in the media, to sharing, mentoring, networking, and always highlighting the best in us. Her life and being are a true lesson in sisterhood."Eve Ensler

-

"With wit, moxie, and infectious curiosity about the world, Pat Mitchell reminds us that to traverse the road to self-actualization, one must court a little danger along the way. Becoming a Dangerous Woman is a tour de force worthy of every nightstand."Kimberlé Crenshaw, professor of law at Columbia Law School and UCLA

-

"Becoming a Dangerous Woman is an irresistible handbook for women who want to be powerful and show up for other women--the way Pat Mitchell has her whole life. May it inspire the dangerous woman in all of us."Ai-jen Poo, director of the National Workers Alliance and author of The Age of Dignity

-

"Dangerous women are the antidote to dangerous times. Thank you, Pat Mitchell, for your courageous work and enduring leadership-you inspire us all to put aside our fears so we can do the work needed to fix our broken world."Jessica Zitter, M.D., author of Extreme Measures

-

"Her impressive bio doesn't do her justice."Forbes

-

"This book is riveting history lesson, case study in fierce feminist leadership, truly useful advice from a trusted girlfriend, and radical call-to-action all rolled into one page-turning package. I inhaled Pat's life story, in large part, because I was blown away by her unshakable honesty--about power struggles at work, about men and money, about sex and violence. Apparently there's no time for fear or bullshit in your 70s. I can't wait."Courtney E. Martin, author of The New Better Off: Reinventing the American Dream

-

"The life and times of award-winning journalist and producer Pat Mitchell is an inspiration for all who wish to see positive change in the world . . . Pat is a tour de force whose continued advocacy for access and equal opportunities for women is to be applauded."Deborah Calmeyer, founder and CEO of Roar Africa

-

"If you listen to Pat Mitchell and remain uninspired, it may be time for an undertaker."Jacqueline Cutler, MediaVillage

-

"Mitchell's notion of the benefits of being dangerous becomes a life philosophy that others can follow."Booklist

-

"Engrossing . . . Mitchell tells a remarkable story of perseverance that will inspire any reader."Publishers Weekly (starred review)