Promotion

Use code SPRING26 for 20% off sitewide.

By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

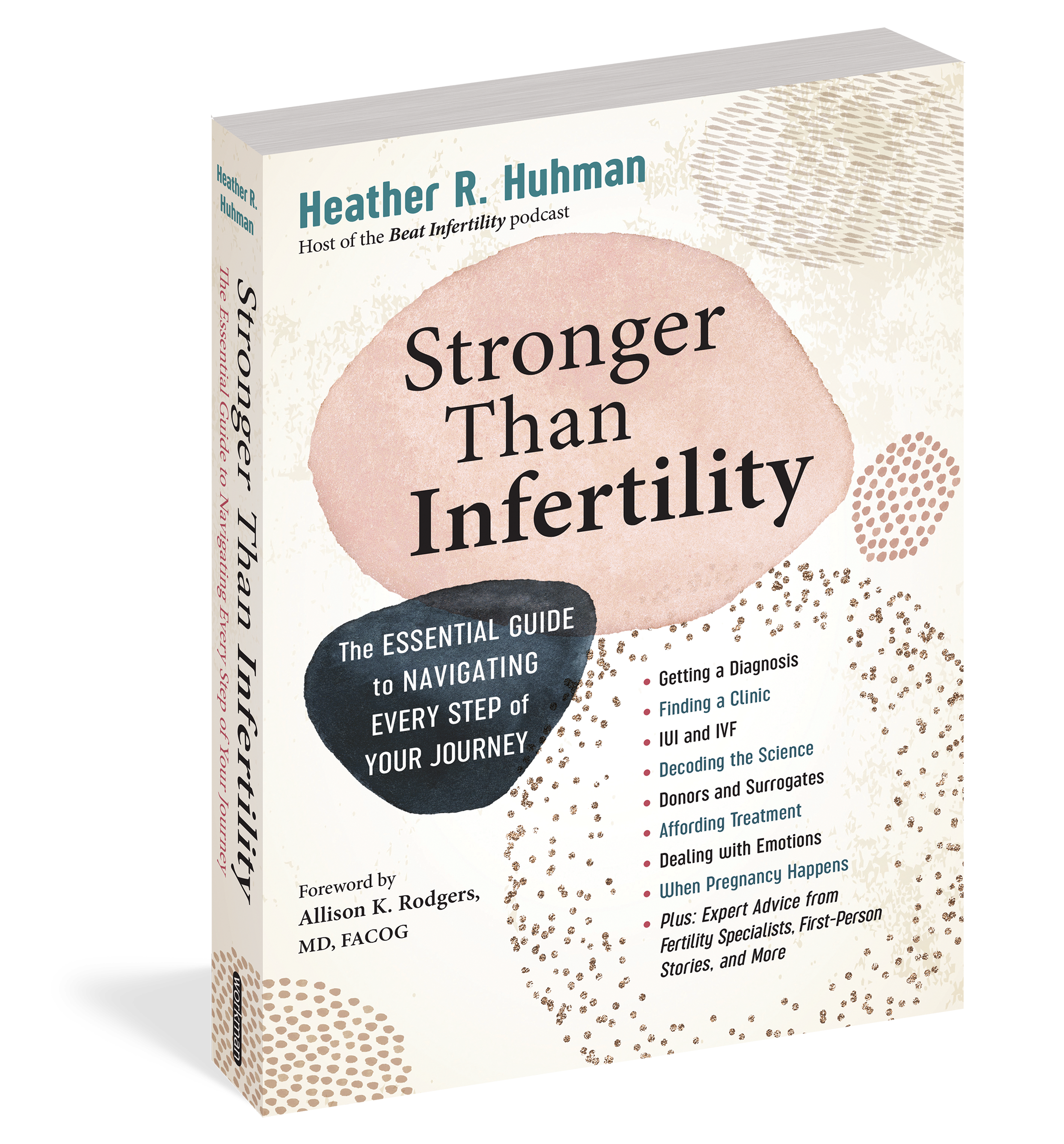

Stronger Than Infertility

The Essential Guide to Navigating Every Step of Your Journey

Contributors

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Aug 8, 2023

- Page Count

- 496 pages

- Publisher

- Workman Publishing Company

- ISBN-13

- 9781523504329

Price

$24.99Price

$30.99 CADFormat

Format:

- Trade Paperback $24.99 $30.99 CAD

- ebook $12.99 $16.99 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged) $44.99

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around August 8, 2023. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

This indispensable, comprehensive, and accessible reference book to infertility provides people with the tools they need to be their own best advocates as they navigate fertility treatments and highs and lows of their infertility journey.

Author Heather Huhman guides readers through every stage of the process—from knowing when to seek medical advice to parenting after infertility, and everything in between. There’s the medical nitty gritty: getting a diagnosis (or not); selecting a fertility clinic that’s right for you; understanding IUI and IVF and genetic testing; a comprehensive list of medications and their side effects, and much more. There are emotional high and lows: staying hopeful while managing grief and depression, maintaining and strengthening your relationship, and navigating religious and ethical concerns. And then there is the practical and often complicated questions around affording treatments, dealing with your workplace (including the military), and everything you need to know about insurance and fertility treatments.Stronger Than Infertility breaks down complicated clinical information and expert medical advice from top specialists in the field. The book includes first-person stories and hard-won advice from women who have been down this long and often painful road (Huhman included) and offers a clear-eyed look at the emotional and psychological landmines that come with the journey. The result is a book that inspires as much as it educates and is a much-needed source of support and inspiration for readers hungry for understanding and hope.