Promotion

Use code MOM24 for 20% off site wide + free shipping over $45

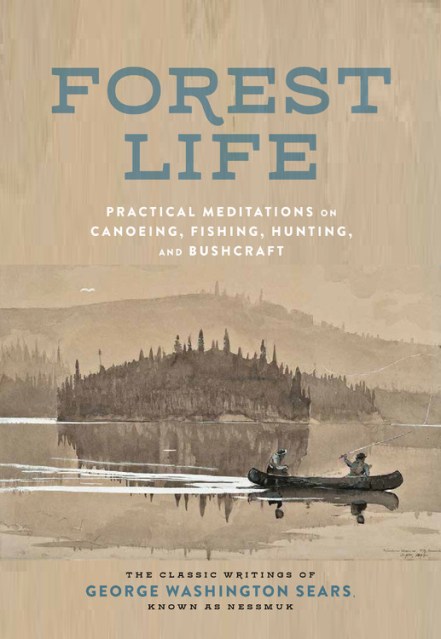

Forest Life

Practical Meditations on Canoeing, Fishing, Hunting, and Bushcraft

Contributors

Formats and Prices

Price

$19.99Price

$25.99 CADFormat

Format:

- Hardcover $19.99 $25.99 CAD

- ebook $12.99 $16.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around October 23, 2018. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

Forest Life collects George Washington Sears’ timeless writing about the joys of exploring the wilderness, edited for a modern audience. In text both practical and inspirational, Sears’ provides enduring wisdom about trips into the woods and lakes, including equipment, campfires, fishing, camp cooking, traveling light, and canoes.

The original “forest bather,” Sears wanted others to enjoy the woods as he did. He published Woodcraft in 1884 to help prepare skillful, self-reliant woodsman and to extol the restorative power of nature. In addition to Woodcraft, Forest Life contains many of his articles from Forest and Stream, as well as his nature poetry.

Sears is especially eloquent about canoeing, which he helped popularize with published tales of his adventures. In 1883, when he was 61 years old and suffering from tuberculosis, he used a 9-foot, 10-1/2 pound canoe to travel 266 miles through the Adirondacks, writing, “The easy, gentle rocking of the canoe was the best incentive to drowsiness I ever found, and by night or day was nearly certain to send me into dreamland.”

This edition features period etchings of scenes, people, flora, and fauna of the Adirondacks, and is the ideal gift book for the outdoor enthusiast.

Genre:

- On Sale

- Oct 23, 2018

- Page Count

- 288 pages

- Publisher

- Black Dog & Leventhal

- ISBN-13

- 9780762465538

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use