By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

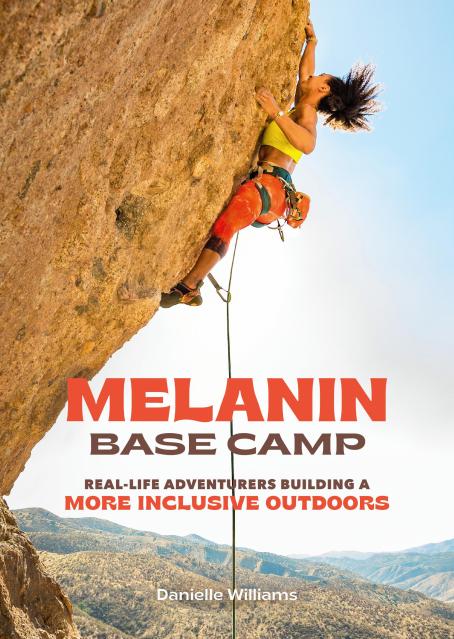

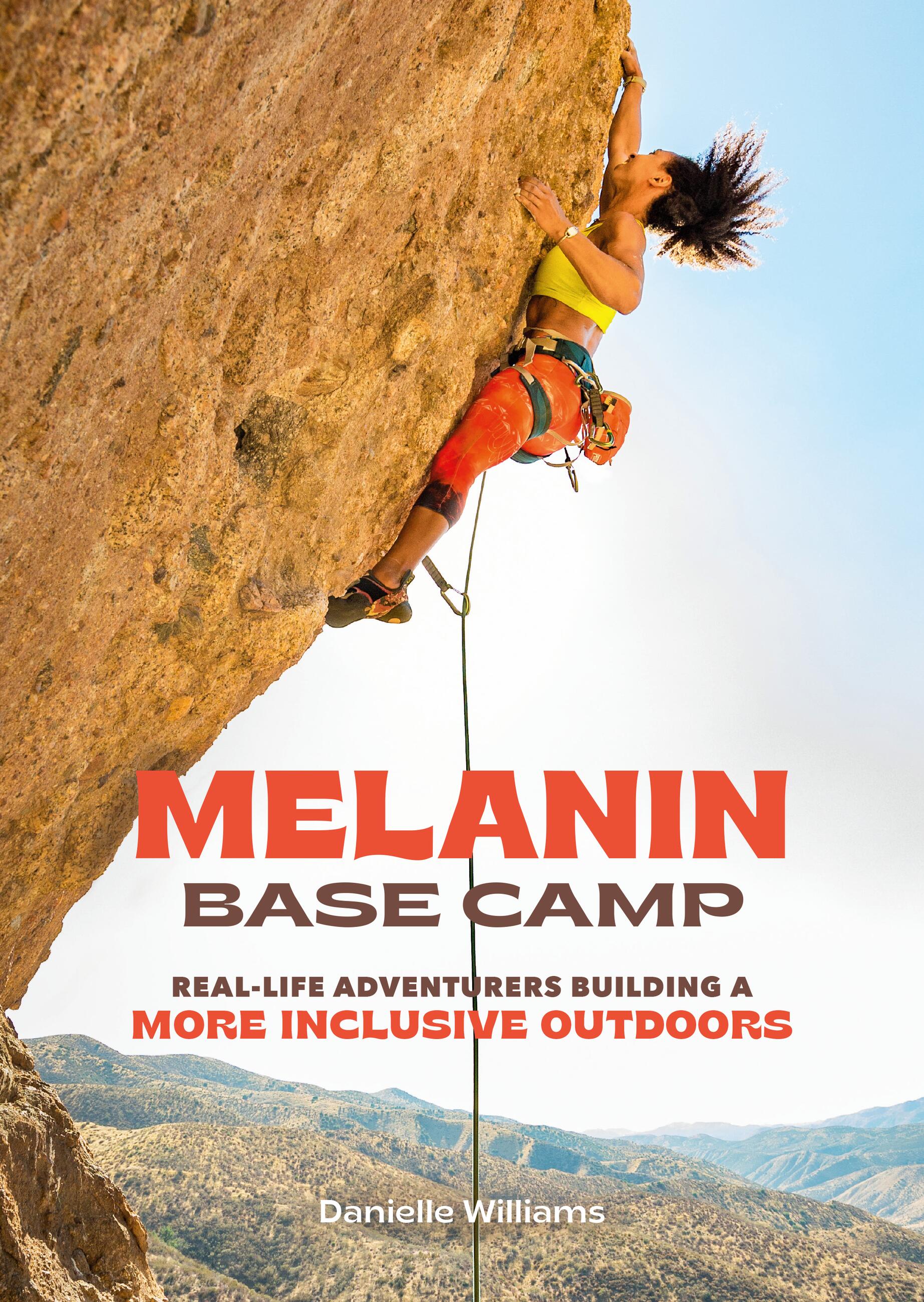

Melanin Base Camp

Real-Life Adventurers Building a More Inclusive Outdoors

Contributors

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Mar 21, 2023

- Page Count

- 240 pages

- Publisher

- Black Dog & Leventhal

- ISBN-13

- 9780762479320

Price

$30.00Price

$38.00 CADFormat

Format:

- Hardcover $30.00 $38.00 CAD

- ebook $14.99 $19.99 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged) $18.99

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around March 21, 2023. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

Beautiful, empowering, and exhilarating, Melanin Base Camp is a celebration of underrepresented BIPOC adventurers that will challenge you to rethink your perceptions of what an outdoorsy individual looks like and inspire you to being your own adventure.

Danielle Williams, skydiver and founder of the online community Melanin Base Camp, profiles dozens of adventurers pushing the boundaries of inclusion and equity in the outdoors. These compelling narratives include a mother whose love of hiking led her to found a nonprofit to expose BIPOC children to the wonders of the outdoors and a mountain biker who, despite at first dealing with unwelcome glances and hostility on trails, went on to become a blogger who writes about justice and diversity in natural spaces.

Also included is a guide to outdoor allyship that explores sometimes challenging topics to help all of us create a more inclusive community, whether you bike, climb, hike, or paddle. Join us as we work together to increase representation and opportunities for people of color in outdoor adventure sports.

Genre:

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use