Promotion

Use code FALL24 for 20% off sitewide!

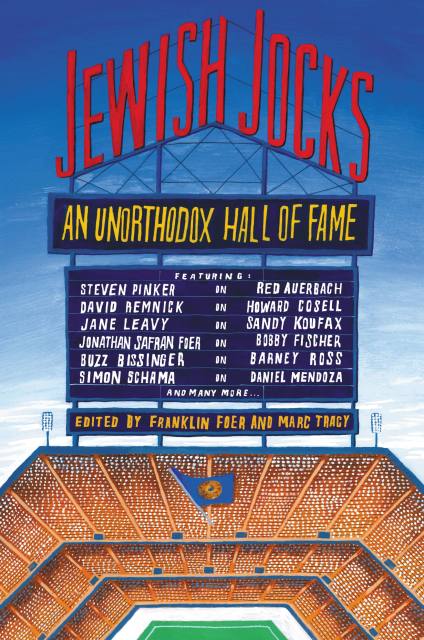

Jewish Jocks

An Unorthodox Hall of Fame

Contributors

Edited by Franklin Foer

Edited by Marc Tracy

Formats and Prices

Price

$9.99Price

$12.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $9.99 $12.99 CAD

- Trade Paperback $21.99 $28.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around October 30, 2012. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

A collection of essays by today’s preeminent writers on significant Jewish figures in sports, told with humor, heart, and an eye toward the ever elusive question of Jewish identity.

Contributors include some of today’s most celebrated writers covering a vast assortment of topics, including David Remnick on the biggest mouth in sports, Howard Cosell; Jonathan Safran Foer on the prodigious and pugnacious Bobby Fischer; Man Booker Prize-winner Howard Jacobson writing elegantly on Marty Reisman, America’s greatest ping-pong player and the sport’s ultimate showman. Deborah Lipstadt examines the continuing legacy of the Munich Massacre, the fortieth anniversary of which coincided with the 2012 London Olympics. Jane Leavy reveals why Sandy Koufax agreed to attend her daughter’s bat mitzvah. And we learn how Don Lerman single-handedly thrust competitive eating into the public eye with three pounds of butter and 120 jalapeño peppers. These essays are supplemented by a cover design and illustrations throughout by Mark Ulriksen.

From settlement houses to stadiums and everywhere in between, Jewish Jock features men and women who do not always fit the standard athletic mold. Rather, they utilized talents long prized by a people of the book (and a people of commerce) to game these games to their advantage, in turn forcing the rest of the world to either copy their methods — or be left in their dust.

Genre:

- On Sale

- Oct 30, 2012

- Page Count

- 304 pages

- Publisher

- Twelve

- ISBN-13

- 9781455516117

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use