By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

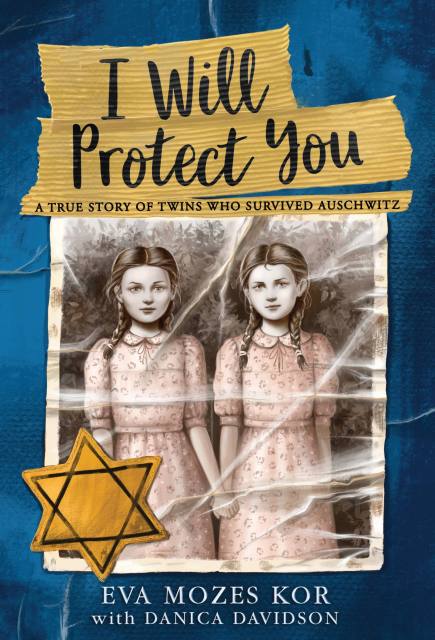

I Will Protect You

A True Story of Twins Who Survived Auschwitz

Contributors

With Danica Davidson

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Apr 5, 2022

- Page Count

- 240 pages

- Publisher

- Little, Brown Books for Young Readers

- ISBN-13

- 9780316460620

Price

$7.99Price

$9.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $7.99 $9.99 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged) $18.99

- Trade Paperback $9.99 $12.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around April 5, 2022. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

Eva and her identical twin sister, Miriam, had a mostly happy childhood. Theirs was the only Jewish family in their small village in the Transylvanian mountains, but they didn't think much of it until anti-Semitism reared its ugly head in their school. Then, in 1944, ten-year-old Eva and her family were deported to Auschwitz. At its gates, Eva and Miriam were separated from their parents and other siblings, selected as subjects for Dr. Mengele's infamous medical experiments.

During the course of the war, Mengele would experiment on 3,000 twins. Only 160 would survive–including Eva and Miriam.

Writing with her friend Danica Davidson, Eva reveals how two young girls were able to survive the unimaginable cruelty of the Nazi regime, while also eventually finding healing and the capacity to forgive. Spare and poignant, I Will Protect You is a vital memoir of survival, loss, and forgiveness.

-

A Children's Book Council Teacher FavoriteAndrew Aydin, National Book Award winning and #1 New York Times bestselling creator and coauthor of March

“Emotional and captivating; this story is a great tool for a younger audience wishing to understand the harsh realities faced by twin children in concentration camps.” -

"The gripping story and fast-paced chapters make this a valuable purchase for reluctant readers. In a world where most people who lived the Holocaust are no longer with us, this book is a sincere and truthful reminder of this horrific event."School Library Journal

-

"Powerful… Unflinching in its first-person telling, the narrative is carried by its narrator's passionate conviction, per an afterword, that 'memories will provide the necessary fuel to light the way to hope.'"Publishers Weekly

-

“A compelling story of survival.”Booklist

-

"Bright and compelling, Eva invites young readers to plant flowers of knowledge, love, and acceptance in their own minds. Moving and informative; a powerful resource for Holocaust education."Kirkus Reviews

-

"Few Holocaust survivors have had Eva Mozes Kor’s impact. Together with Danica Davidson, the story of this young girl is narrated in a manner that I would not have thought possible, faithful to the history and yet accessible to young readers. Read this work and meet a person you will never forget with a story that is worth telling and retelling."Michael Berenbaum, award-winning author; Professor of Jewish Studies, American Jewish University; and former Director of the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum's Holocaust Research Institute

-

"Danica Davidson has taken Eva Mozes Kor’s story and woven it into a straightforward yet harrowing account of astonishing courage in the face of unspeakable depravity. An important and powerful contribution to the field of Holocaust literature for children."Yona Zeldis McDonough, author of The Bicycle Spy and The Doll with the Yellow Star

-

"I Will Protect You is a well-written memoir, a gripping story of prejudice, hatred, horror and forgiveness. It belongs on every shelf of books for young readers on the Nazi Holocaust and of books attacking racism."David A. Adler, award-winning author of The Number On My Grandfather's Arm, We Remember The Holocaust, and many other books

-

"This riveting eyewitness account of the Nazi horrors, written in a way that a sympathetic young reader can understand, is needed now more than ever, in our present age of growing violence, intolerance and irrational hatred of the Other."David Small, #1 New York Times bestselling author of Stitches

-

"The Holocaust seen through the eyes of a ten-year-old girl and her twin sister. Harrowing but ultimately redemptive, I Will Protect You is a story of irrational hope and courage."Mark V Long, NY Times bestselling author The Silence of Our Friends

-

"I Will Protect You is one of the best Holocaust memoirs I have ever read (and I have read many). The fact that twin sisters Eva and Miriam survived Dr. Mengele’s cruel and barbaric experiments is nothing short of miraculous. Eva’s fierce determination to live and to ensure her sister’s survival moved me deeply. Her strength, courage, resourcefulness, and intelligence are profound. This book illuminates the human spirit and proves that even in the very worst circumstances, kindness can be found. I am a better person for having read this book."Lesléa Newman, author Gittel’s Journey: An Ellis Island Story

-

"How can we best teach our children about the world? This extraordinary story of a Holocaust survivor (one of the infamous Mengele twins), shows both the astounding history that lay the groundwork for the rise and fall of Nazi Germany, as well as being a deeply personal (and page-turning) story of one very brave and determined young Jewish girl caught in its midst. What better way to ensure that our children really are protected from something like this ever happening again—we can protect them with knowledge, understanding, determination, and hope."Caroline Leavitt, New York Times bestselling author of With or Without You

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use