By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

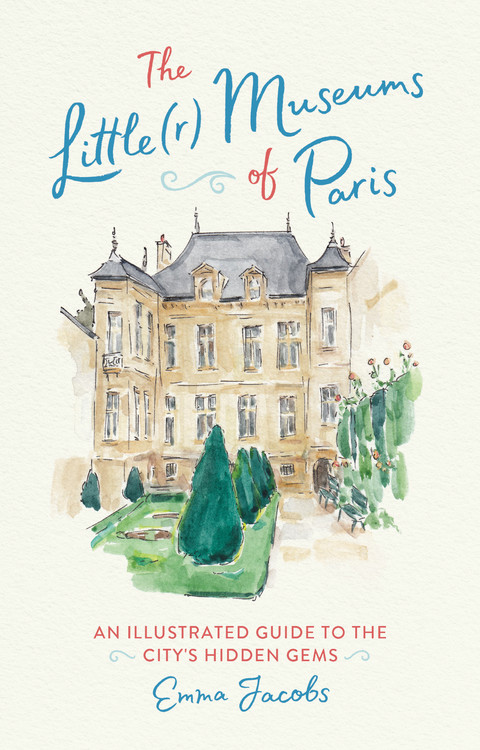

The Little(r) Museums of Paris

An Illustrated Guide to the City's Hidden Gems

Contributors

By Emma Jacobs

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Jun 4, 2019

- Page Count

- 192 pages

- Publisher

- Running Press

- ISBN-13

- 9780762466399

Price

$20.00Price

$26.00 CADFormat

Format:

- Hardcover $20.00 $26.00 CAD

- ebook $12.99 $16.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around June 4, 2019. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

Discover a new side of Paris, hidden in plain sight, with this beautifully illustrated guide to the city’s smaller collections and best-kept secrets, from artists’ studios to scientific museums.

A visit to Paris can often seem like a highlight reel — the Louvre, the Musee d’Orsay, the Eiffel Tower. But Paris isn’t only about the big attractions; in fact, some might say it’s the offbeat destinations that hold the greatest treasures. The Little(r) Museums of Paris takes a whimsical journey through these smaller destinations, from the fantastical to the bizarre, offering both a guide to the city and inspiration for armchair travelers.Rather than traveling by neighborhood, this charming guide explores the different types of institutions nestled within Paris, from time capsules like the Musee Nissim de Camondo to explorations of the world beyond the city limits, including the Institute of the Arab World. Readers will peek behind the curtains of artists’ apartments and into the microscopes of collections of scientific oddities. Each entry opens up a new world of adventure, with a description of the museum’s collection, as well as a short history, watercolor illustrations, and a miniature map. For residents and visitors alike, the captivating illustrations and deeply-researched yet approachable writing will encourage greater appreciation of the cultural diversity, history, and colorful characters that give Paris that je ne sais quoi.

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use