Promotion

Use code SPRING26 for 20% off sitewide.

By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

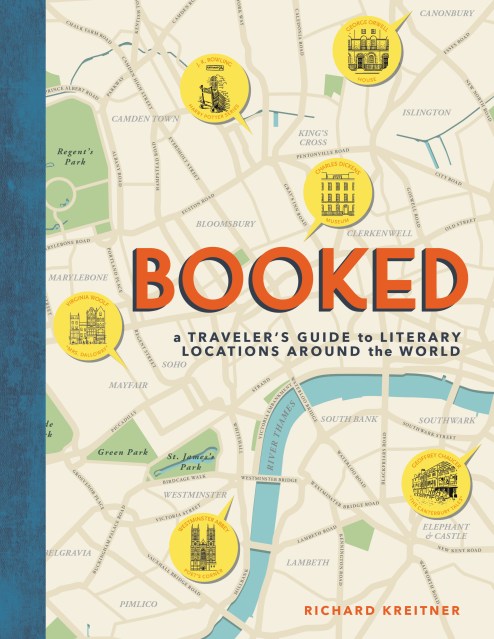

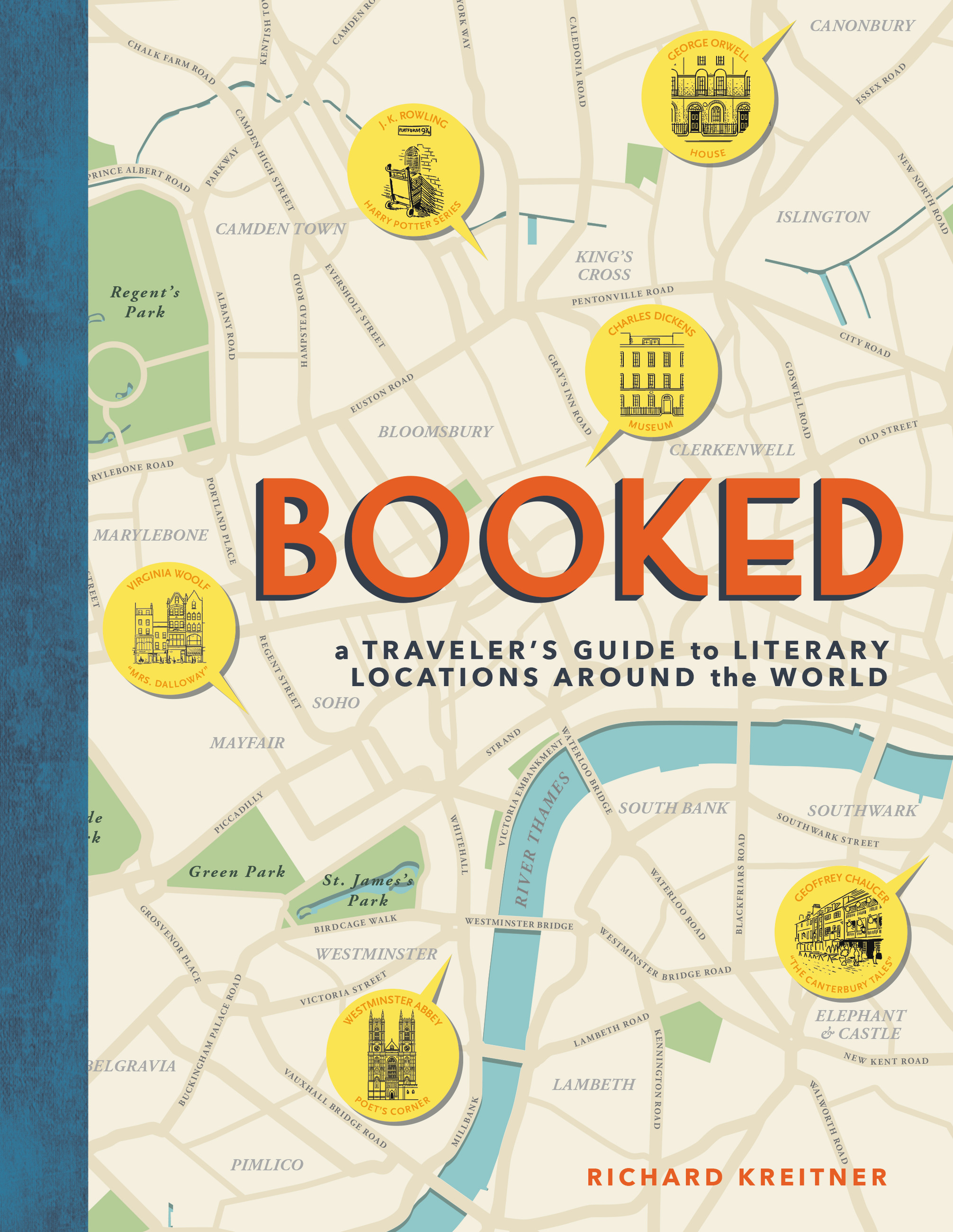

Booked

A Traveler's Guide to Literary Locations Around the World

Contributors

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Apr 23, 2019

- Page Count

- 240 pages

- Publisher

- Black Dog & Leventhal

- ISBN-13

- 9780316420877

Price

$29.99Price

$38.99 CADFormat

Format:

- Hardcover $29.99 $38.99 CAD

- ebook $15.99 $20.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around April 23, 2019. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

A practical, armchair travel guide that explores eighty of the most iconic literary locations from all over the globe that you can actually visit.

A must-have for every fan of literature, Booked inspires readers to follow in their favorite characters footsteps by visiting the real-life locations portrayed in beloved novels including the Monroeville, Alabama courthouse in To Kill a Mockingbird, Chatsworth House, the inspiration for Pemberley in Pride and Prejudice, and the Kyoto Bridge from Memoirs of a Geisha. The full-color photographs throughout reveal the settings readers have imagined again and again in their favorite books.

Organized by regions all around the world, author Richard Kreitner explains the importance of each literary landmark including the connection to the author and novel, cultural significance, historical information, and little-known facts about the location. He also includes travel advice like addresses and must-see spots.

Booked features special sections on cities that inspired countless literary works like a round of locations in Brooklyn from Betty Smith’s iconic A Tree Grows in Brooklyn to Jonathan Lethem’s Motherless Brooklyn and a look at the New Orleans of Tennessee Williams and Anne Rice.

Locations include:

Central Park, NYC (The Catcher in the Rye, JD Salinger)

Forks, Washington (Twilight, Stephanie Meyer)

Prince Edward Island, Canada (Anne of Green Gables, Lucy Maud Montgomery)

Kingston Penitentiary, Ontario (Alias Grace, Margaret Atwood)

Holcomb, Kansas (In Cold Blood, Truman Capote)

London, England (White Teeth, Zadie Smith)

Paris, France (Hunchback of Notre Dame, Victor Hugo)

Segovia, Spain, (For Whom the Bell Tolls, Ernest Hemingway)

Kyoto, Japan (Memoirs of a Geisha, Arthur Golden)

Genre:

-

"For some readers, the printed page isn't enough. With this book, they can continue the story by going to the source, whether than means Forks, Washington (Twilight), Segovia, Spain (For Whom the Bell Tolls) or London (White Teeth)."The Washington Post, 2019 Holiday Gift Guide

-

"Literary sites to be added to any reader's itinerary, including Thoreau's Massachusetts cabin, the Monroeville County Courthouse where Atticus Finch made his case for the defense, and the Mexico City cafe that inspired Robert Bolaño."The New York Times, 2019 Holiday Gift Guide

-

"If you like exploring real places related to literature, this book is a good place to start."GeekDad

-

"Booked provides full-color photographs of 80 famous literary locations, including To Kill a Mockingbird's courthouse in Monroeville, Ala.; the inspiration for Pride and Prejudice's Pemberley; and Memoirs of a Geisha's Kyoto Bridge."Publishers Weekly, Spring Announcements feature

-

"[Booked] will whet your appetite to visit the places you have read about. With color photos and engaging descriptions of Sinclair Lewis' Main Street, Jame Joyce's Dublin, Basho's Japan and scores of other places, Booked will inspire you to put down your book and head into the world."The Star Tribune