Promotion

Use code MOM24 for 20% off site wide + free shipping over $45

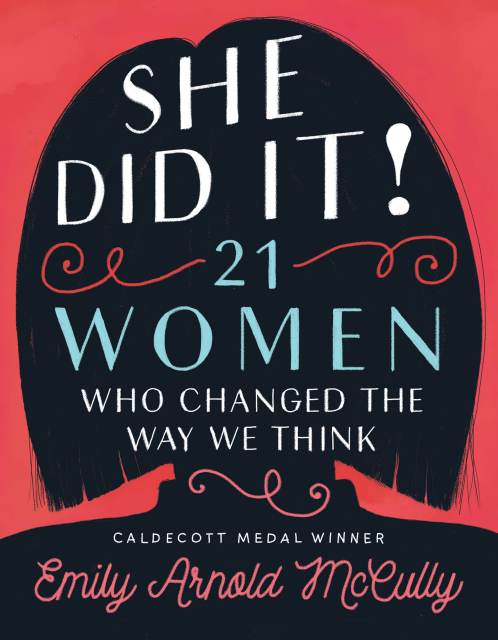

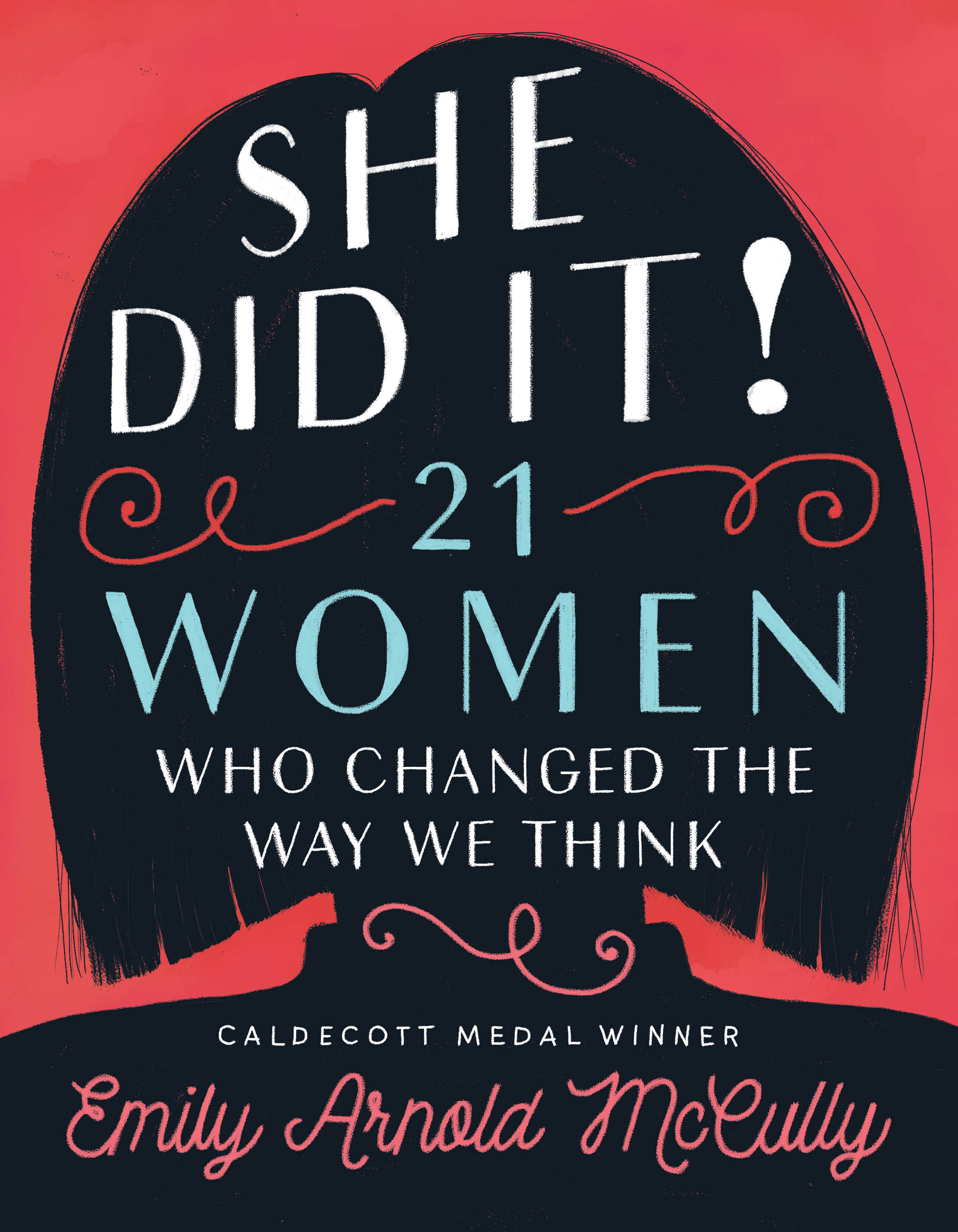

She Did It!

21 Women Who Changed the Way We Think

Contributors

Illustrated by Emily Arnold McCully

Cover design or artwork by Emily Arnold McCully

Formats and Prices

Price

$12.99Price

$16.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $12.99 $16.99 CAD

- Hardcover $21.99 $21.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around November 4, 2018. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

The subjects profiled include:

Jane Addams Ethel Percy Drusilla Baker Gertrude BergRachel CarsonShirley ChisholmJoan CooneyIsadora DuncanBarbara GittingsTemple GrandinGrace HopperDolores HuertaBillie Jean KingDorothea LangePatsy MinkVera RubinMargaret SangerGladys TantaquidgeonIda M. TarbellMadame C. J. WalkerAlice WatersSecond Wave Feminism

Genre:

-

"A rich and multilayered celebration of women's innovation and perseverance."Publishers Weekly

-

"The illustrations, consisting of portraits and spot art over white backgrounds, are striking and whimsical. A thorough introduction to the women's-rights movement and its American origins."Booklist

-

"[T]his book provides insights into the lives of important women, many of whom have otherwise yet to be featured in nonfiction for young readers."Kirkus Reviews

- On Sale

- Nov 4, 2018

- Page Count

- 272 pages

- Publisher

- Little, Brown Books for Young Readers

- ISBN-13

- 9781368027380

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use