Promotion

Use code SPRING26 for 20% off sitewide.

By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

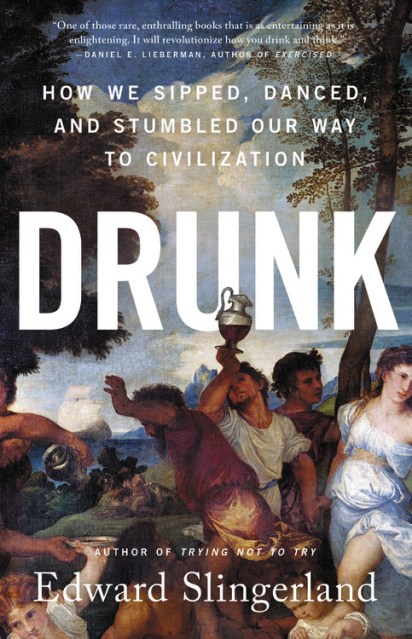

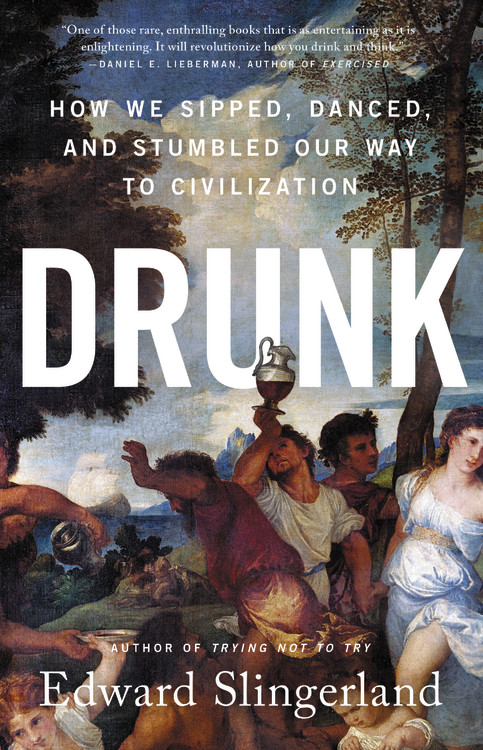

Drunk

How We Sipped, Danced, and Stumbled Our Way to Civilization

Contributors

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Jun 1, 2021

- Page Count

- 384 pages

- Publisher

- Little Brown Spark

- ISBN-13

- 9780316453387

Price

$29.00Price

$37.00 CADFormat

Format:

- Hardcover $29.00 $37.00 CAD

- ebook $11.99 $15.99 CAD

- Trade Paperback $21.99 $28.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around June 1, 2021. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

An “entertaining and enlightening” deep dive into the alcohol-soaked origins of civilization—and the evolutionary roots of humanity’s appetite for intoxication (Daniel E. Lieberman, author of Exercised).

While plenty of entertaining books have been written about the history of alcohol and other intoxicants, none have offered a comprehensive, convincing answer to the basic question of why humans want to get high in the first place.

Drunk elegantly cuts through the tangle of urban legends and anecdotal impressions that surround our notions of intoxication to provide the first rigorous, scientifically-grounded explanation for our love of alcohol. Drawing on evidence from archaeology, history, cognitive neuroscience, psychopharmacology, social psychology, literature, and genetics, Drunk shows that our taste for chemical intoxicants is not an evolutionary mistake, as we are so often told. In fact, intoxication helps solve a number of distinctively human challenges: enhancing creativity, alleviating stress, building trust, and pulling off the miracle of getting fiercely tribal primates to cooperate with strangers. Our desire to get drunk, along with the individual and social benefits provided by drunkenness, played a crucial role in sparking the rise of the first large-scale societies. We would not have civilization without intoxication.

From marauding Vikings and bacchanalian orgies to sex-starved fruit flies, blind cave fish, and problem-solving crows, Drunk is packed with fascinating case studies and engaging science, as well as practical takeaways for individuals and communities. The result is a captivating and long overdue investigation into humanity’s oldest indulgence—one that explains not only why we want to get drunk, but also how it might actually be good for us to tie one on now and then.

-

“Wide-ranging and provocative…Drunk helpfully synthesizes the literature, then underlines its most radical implication: Humans aren’t merely built to get buzzed—getting buzzed helped humans build civilization.”The Atlantic

-

"A rowdy banquet of a book...A refreshingly erudite rejoinder to the prevailing wisdom."New York Times

-

"Absorbing...Slingerland makes a compelling case that human societies have been positively shaped by alcohol.”The Wall Street Journal

-

“Engrossing. This heady book is best savored as a fresh take on a contentious topic.”New Scientist

-

"Compelling and, above all, a whole lot of irreverent fun."Smithsonian Magazine

-

"A witty and erudite homage to alcohol."City Journal

-

“A superb panoramic study of intoxication…capacious and wisely humane.”The World of Fine Wine

-

“Drunk is one of those rare, enthralling books that is as entertaining as it is enlightening. Slingerland’s uproarious and erudite exploration of the history, anthropology, and science of intoxicants will revolutionize how you drink and think.”Daniel E. Lieberman, Edwin M Lerner II Professor of Biological Sciences at Harvard University, and author of Exercised

-

“Drunk is a punchy and stimulating intellectual cocktail that takes a fresh look at one of our species’ most puzzling obsessions—our routine consumption of sublethal dosages of a psychoactive poison. Despite a deep erudition that effortlessly weaves together history, anthropology, genetics, and chemistry, Slingerland’s book feels like a chat with an old friend over a couple of pints. You’ll learn a lot, but you won’t notice, because you’ll be so entertained.”Joseph Henrich, author of The WEIRDest People in World, and Professor and Chair of Human Evolutionary Biology at Harvard University

-

“Does booze make us human? In this wide-ranging, provocative, and very funny exploration, Edward Slingerland makes an excellent case that intoxication is a powerful force for trust and love. From the first paragraph about the appeal of masturbation, Twinkies, and alcohol, to the rousing ending where Slingerland urges us to leave a place for ecstasy in our lives, Drunk is a delight.”Paul Bloom, author of Against Empathy: The Case for Rational Compassion

-

"A brilliant and definitive book. Alcohol has been used and abused by more people in more places at more times than all other intoxicants combined. The story of drinking is, indeed, the story of humanity, and Edward Slingerland tells it with endearing wit, irreverence, wisdom, and profound insight. "Wade Davis, author of Magdalena: River of Dreams

-

“Witty, wise, effervescent, and slyly irreverent. This sparkling chronicle belongs on the shelf of every thinking person who enjoys a drink from time to time.”Janet Chrzan, author of Alcohol: Social Drinking in Cultural Context

-

“An eminently enjoyable, irreverent, and informative romp through the world of intoxicants. Drunk is a milestone in the field.”Brian Hayden, author of The Power of Feasts

-

“To understand why people drink is to tap into the very core of human experience. Professor Slingerland seamlessly weaves together observations from a dizzying array of disciplines across the sciences and humanities. In so doing, he provides provocative insights regarding why we prize drinking and offers practical suggestions about how we might drink responsibly and better integrate drinking and nondrinking members of society. Read the first few paragraphs and you will immediately realize that you are in for a truly engrossing and delightful read! Read further and you also realize that you’re gaining a cutting-edge understanding of both the pleasures and the hazards of drinking. Slingerland has deftly managed to educate, surprise, and entertain while distilling a complex alcohol literature to address just why we humans drink to the point of intoxication.”Michael Sayette, PhD, Professor of Psychology and Psychiatry, and Director of the Alcohol and Smoking Research Laboratory, University of Pittsburgh

-

"This book is a love letter to Dionysius. Even as it aroused memories of patients whose lives were ruined by alcohol, Drunk made me appreciate the value as well as the pleasure of drinking with friends, and of reading wonderful books.”Randolph M. Nesse, M.D., author of Good Reasons for Bad Feelings, and Founding Director of The Center for Evolution and Medicine at Arizona State University

-

“Drunk induces a thrilling intellectual buzz. Edward Slingerland plunges his bar spoon into the rich ethnographic, archaeological, psychological, and historic literatures, stirs vigorously, and produces a cocktail of brilliant and novel insights about the role that alcohol played in the development of human civilization, and its continued importance today. He’s more entertaining than your typical bartender, and the drink he’s mixed is one we’ll be sipping, absorbing, and savoring for quite some time. Cheers!”Richard Sosis, coauthor of Religion Evolving, and James Barnett Professor of Humanistic Anthropology, University of Connecticut

-

“Cooperation on a large scale is vital to the success of contemporary society. In this fascinating, funny and readable book, Professor Slingerland presents the case that alcohol is part of a cultural toolkit honed over thousands of years to help us all get along in a complex world. Drunk shines a new light on our love-hate relationship with booze.”Greg Wadley, University of Melbourne

-

“A fascinating account of our obsession with the demon drink."Iain Gately, author of Drink: A Cultural History of Alcohol

-

“Slingerland … weaves modern scientific studies with ancient mythology. An illuminating yet conversational study that takes an anthropological approach to a widespread and often puzzling human behavior.”Jeffrey Meyer, Library Journal

-

“A spirited look at drinking”Kirkus

-

“A witty and well-informed narrator, Slingerland ranges across a wide range of academic fields to make his case. Readers will toast this praiseworthy study.”Publishers Weekly

-

“This enlightening and scientific book, which explains how alcohol has lubricated innovation and social trust through history, is a breath of unconventionality, and even risk-taking, in a North American society that is increasingly fixating on puritanism, ‘safetyism’ and orthodoxy of opinion.”The Province

-

"Elegant, well-argued, and occasionally dryly humorous."Master of Malt