Promotion

Use code MOM24 for 20% off site wide + free shipping over $45

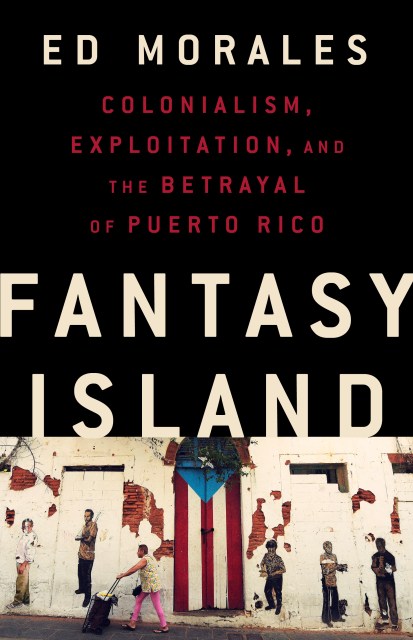

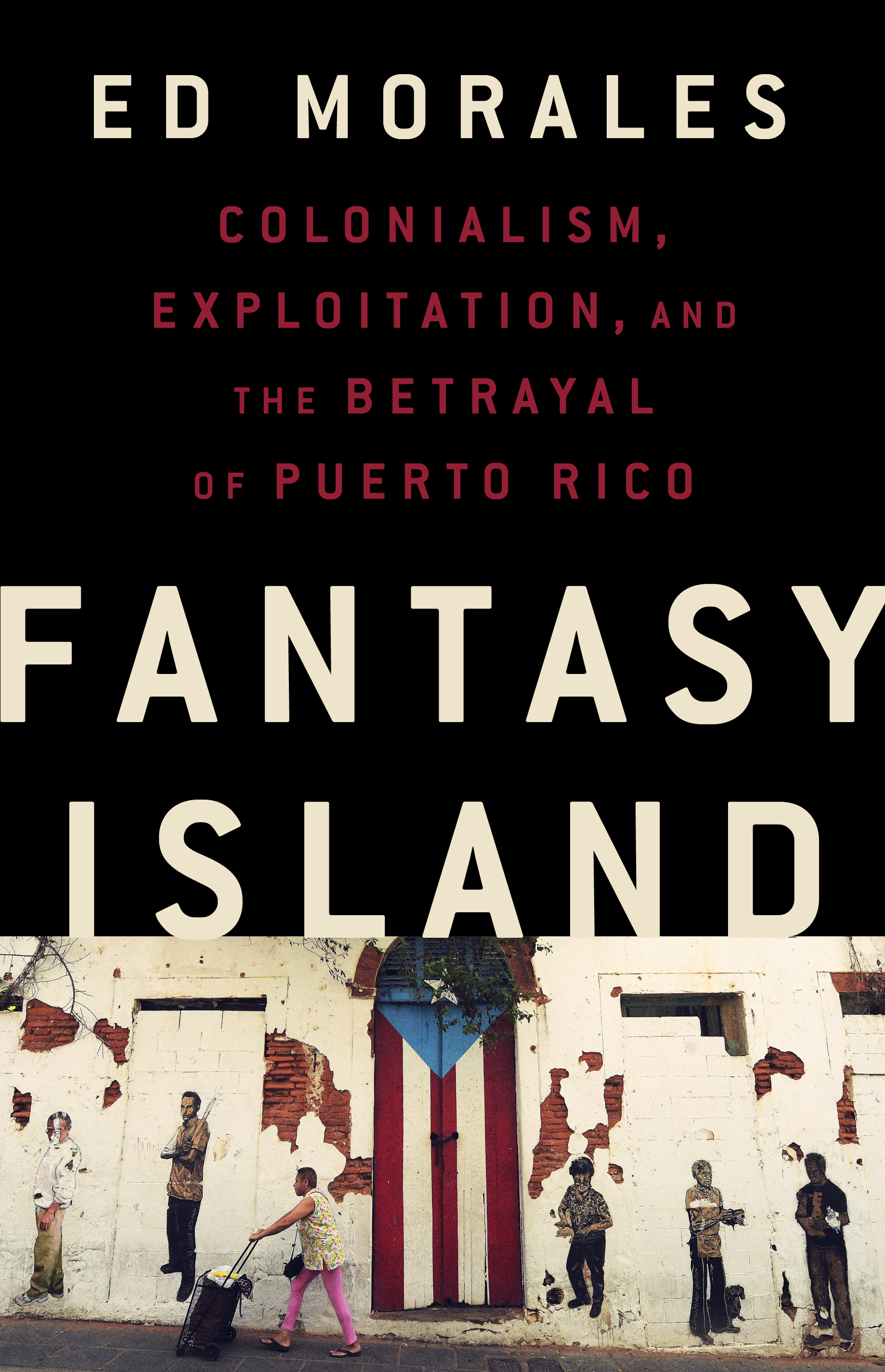

Fantasy Island

Colonialism, Exploitation, and the Betrayal of Puerto Rico

Contributors

By Ed Morales

Formats and Prices

Price

$16.99Price

$21.99 CADFormat

Format:

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around September 10, 2019. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

A crucial, clear-eyed accounting of Puerto Rico’s 122 years as a colony of the US.

Since its acquisition by the US in 1898, Puerto Rico has served as a testing ground for the most aggressive and exploitative US economic, political, and social policies. The devastation that ensued finally grew impossible to ignore in 2017, in the wake of Hurricane María, as the physical destruction compounded the infrastructure collapse and trauma inflicted by the debt crisis. In Fantasy Island, Ed Morales traces how, over the years, Puerto Rico has served as a colonial satellite, a Cold War Caribbean showcase, a dumping ground for US manufactured goods, and a corporate tax shelter. He also shows how it has become a blank canvas for mercenary experiments in disaster capitalism on the frontlines of climate change, hamstrung by internal political corruption and the US federal government’s prioritization of outside financial interests.

Taking readers from San Juan to New York City and back to his family’s home in the Luquillo Mountains, Morales shows us the machinations of financial and political interests in both the US and Puerto Rico, and the resistance efforts of Puerto Rican artists and activists. Through it all, he emphasizes that the only way to stop Puerto Rico from being bled is to let Puerto Ricans take control of their own destiny, going beyond the statehood-commonwealth-independence debate to complete decolonization.

Since its acquisition by the US in 1898, Puerto Rico has served as a testing ground for the most aggressive and exploitative US economic, political, and social policies. The devastation that ensued finally grew impossible to ignore in 2017, in the wake of Hurricane María, as the physical destruction compounded the infrastructure collapse and trauma inflicted by the debt crisis. In Fantasy Island, Ed Morales traces how, over the years, Puerto Rico has served as a colonial satellite, a Cold War Caribbean showcase, a dumping ground for US manufactured goods, and a corporate tax shelter. He also shows how it has become a blank canvas for mercenary experiments in disaster capitalism on the frontlines of climate change, hamstrung by internal political corruption and the US federal government’s prioritization of outside financial interests.

Taking readers from San Juan to New York City and back to his family’s home in the Luquillo Mountains, Morales shows us the machinations of financial and political interests in both the US and Puerto Rico, and the resistance efforts of Puerto Rican artists and activists. Through it all, he emphasizes that the only way to stop Puerto Rico from being bled is to let Puerto Ricans take control of their own destiny, going beyond the statehood-commonwealth-independence debate to complete decolonization.

Genre:

-

"The hurricanes, the debt, the depopulation. Ed Morales has written an urgent, fascinating, and impassioned portrait of Puerto Rico, the world's oldest colony."Daniel Immerwahr, author of How to Hide an Empire: A History of the Greater United States

-

"Ed Morales has put together a compelling indictment of U.S. colonialism in Puerto Rico, based on journalistic and academic sources as well as his personal experiences as a New York-born Puerto Rican who cares deeply about his ancestral homeland. His work is an engaging, compassionate, well-documented, and crisply written analysis of the political, economic, and demographic downturn of the Island, after more than a decade of economic recession and almost two years since hurricane Maria."Jorge Duany, author of Puerto Rico: What Everyone Needs to Know

-

"Ambitious, intimidating, and beautiful...This book will be particularly important to readers with a connection to Puerto Rico and useful and thought-provoking to anyone else seeking to understand capitalism's past, present, and future."Library Journal

-

"[An] eye-opening economic and political history... [Morales's] technical yet impassioned polemic will persuade those with a keen interest in the subject."Publishers Weekly

- On Sale

- Sep 10, 2019

- Page Count

- 352 pages

- Publisher

- Bold Type Books

- ISBN-13

- 9781568588988

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use