Promotion

Use code SPRING26 for 20% off sitewide.

By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

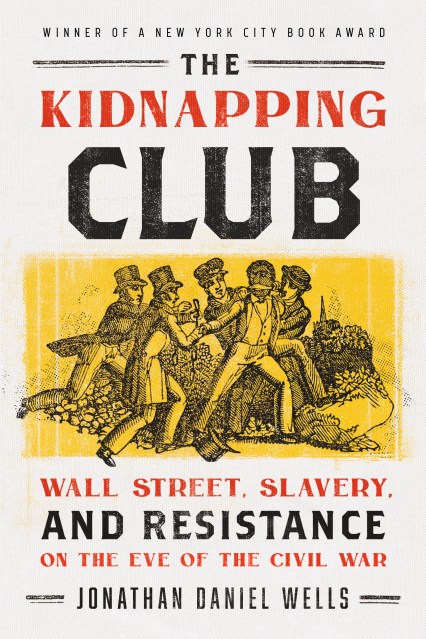

The Kidnapping Club

Wall Street, Slavery, and Resistance on the Eve of the Civil War

Contributors

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Feb 7, 2023

- Page Count

- 368 pages

- Publisher

- Bold Type Books

- ISBN-13

- 9781645030331

Price

$19.99Price

$24.99 CADFormat

Format:

- Trade Paperback $19.99 $24.99 CAD

- ebook $17.99 $21.99 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged) $27.99

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around February 7, 2023. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

In a rapidly changing New York, two forces battled for the city’s soul: the pro-slavery New Yorkers who kept the illegal slave trade alive and well, and the abolitionists fighting for freedom.

We often think of slavery as a southern phenomenon, far removed from the booming cities of the North. But even though slavery had been outlawed in Gotham by the 1830s, Black New Yorkers were not safe. Not only was the city built on the backs of slaves; it was essential in keeping slavery and the slave trade alive.

In The Kidnapping Club, historian Jonathan Daniel Wells tells the story of the powerful network of judges, lawyers, and police officers who circumvented anti-slavery laws by sanctioning the kidnapping of free and fugitive African Americans. Nicknamed “The New York Kidnapping Club,” the group had the tacit support of institutions from Wall Street to Tammany Hall whose wealth depended on the Southern slave and cotton trade. But a small cohort of abolitionists, including Black journalist David Ruggles, organized tirelessly for the rights of Black New Yorkers, often risking their lives in the process.

Taking readers into the bustling streets and ports of America’s great Northern metropolis, The Kidnapping Club is a dramatic account of the ties between slavery and capitalism, the deeply corrupt roots of policing, and the strength of Black activism.

-

"A convincing demonstration of the close links between capitalism and the unconscionable trade in human beings."Kirkus

-

"Lively prose and vivid scenes of New York street life complement the meticulous research. The result is a revealing look at a little-known chapter in the history of racial injustice."Publishers Weekly

-

"With New York City as its backdrop, The Kidnapping Club offers an important and compelling narrative that explores the long struggle for Black freedom and equality. Jonathan Daniel Wells offers a rich and timely account that uncovers a history of racial violence and terror in nineteenth-century Gotham. To no surprise, law enforcement, politicians, and bankers thwarted Black freedom time and time again. But the power and fortitude of Black New Yorkers pressed white citizens to remember and uphold the ideals of a new nation. The Kidnapping Club is a must read for those who want to understand current debates about the intersection of Black lives and structural oppression."Erica Armstrong Dunbar, author of Never Caught: The Washingtons' Relentless Pursuit of Their Runaway Slave, Ona Judge

-

"Jonathan Daniel Wells' The Kidnapping Club is a necessary story of black agency and resistance. Bringing to life the competing strains of humanism and oppression that echo our present-day struggles, Wells paints a portrait of New York that reveals the best of American principles in the bodies of black resistors while showing us the economic complexity and complicity of America's greatest city. It is a brilliant history perfectly suited for our times."Michael Eric Dyson, author of the New York Times bestselling Tears We Cannot Stop and What Truth Sounds Like

-

"The Kidnapping Club maps and specifies both the top-side financial connections between the capitalists of the North and the slavers of the South and the underbelly of police corruption, violence, and kidnapping that knit together. And it manages to combine acute historical analysis with literary drama and a persistent, gentle humanity. You should read it."Walter Johnson, author of The Broken Heart of America: St. Louis and the Violent History of the United States

-

"Nineteenth-century New York City was a battleground for African Americans, who most whites assumed to be undeserving of freedom. Jonathan Wells' The Kidnapping Club brings to life the struggles in the courts and on the streets between those who sought to send blacks to slavery in the south; those who benefited from southern slavery; and the small group of interracial activists who fought against slavery and would eventually prevail in claiming freedom for all regardless of race. From politicians and jurists to newspaper owners, and from bankers to ministers to common laborers, everyone had a stake in the central question of the moment: the legality and morality of slavery and the status of people of African descent in the nation. Wells' gripping narrative brings to life the real-life impact of these questions on every New Yorker, and how the struggle over racial equality affected every sector of life in antebellum New York City."Leslie M. Harris, author of In the Shadow of Slavery: African Americans in New York City, 1626-1863

-

“This history of eighteen-thirties New York probes the city’s entanglement with the slave economy… Wells details how the funding of the cotton trade fueled a nascent Wall Street and admiringly portrays David Ruggles, a Black abolitionist who gave the Kidnapping Club its name and organized to resist it.”The New Yorker

-

“Skillful portrayal of the culture of mid-19th century America…highly recommended for those who like history and readers interested in social justice.”Library Journal

-

“Wells conjures the pungent atmosphere of Manhattan in the early 19th century… Wells writes, one senses, not to memorialize the missing, but to reopen their cases — to make a larger argument about recompense.”The New York Times

-

“Mr. Wells makes a significant contribution to the literature of American slavery with a powerful book."The Wall Street Journal

-

“Readers familiar with “Twelve Years a Slave,” the film based on Solomon Northup’s 1853 slave narrative, might recognize the horror of free Black people forced into Southern enslavement in Wells’s harrowing account of men and women abducted by police officers as they walked the crowded streets of Lower Manhattan…Yet one of Wells’s greatest contributions is his reminder that there were many Solomon Northups.”The New York Times Book Review

-

“The Kidnapping Club offers readers painful account of how many Black people—both free and self-emancipated—were captured, jailed, judged and shipped south to live and suffer as slaves to support the profitable cotton economy… This thoroughly researched account reminds readers that New York was a pro-slavery city even as the nation was engulfed in the Civil War."New York Journal of Books

-

“[A] beautifully researched study…detailing how white authorities actively and repeatedly subverted Black freedom.”Journal of Southern History