Promotion

Use code SPRING26 for 20% off sitewide.

By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

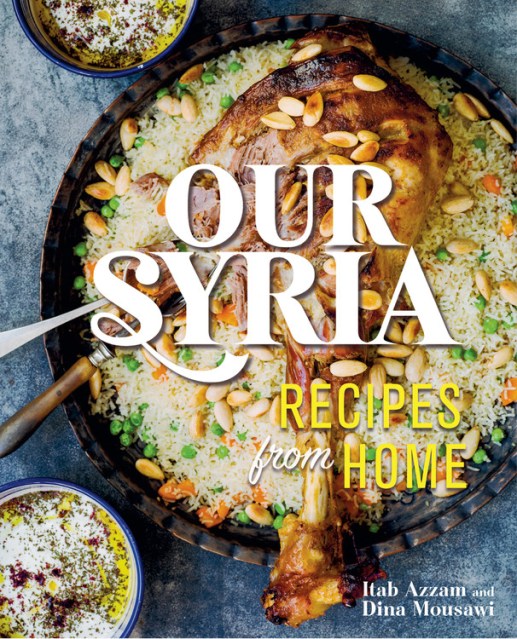

Our Syria

Recipes from Home

Contributors

By Dina Mousawi

By Itab Azzam

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Oct 3, 2017

- Page Count

- 256 pages

- Publisher

- Running Press

- ISBN-13

- 9780762490523

Price

$30.00Price

$39.00 CADFormat

Format:

Hardcover (New edition) $30.00 $39.00 CADThis item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around October 3, 2017. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

Syria has always been the meeting point for the most delicious flavors from East and West, where spices and sweetness collide. Even now, in possibly the country’s darkest hour, Syrian families in tiny apartments from Beirut to Berlin are searching out the best tomatoes, lemons, pomegranates, and parsley to evoke the memory of home, keeping their treasured food history alive across continents.

Friends and passionate cooks Itab and Dina met Syrian women in the Middle East and Europe to collect together the very best recipes from one of the world’s greatest food cultures. They spent months cooking with them, learning their recipes and listening to stories of home. Recipes like the following elicit vibrant images of an ancient culture:

- Hot Yogurt Soup

- Fresh Thyme and Halloumi Salad

- Lamb and Okra Stew

- Chicken Shawarma Wraps

- Semolina and Coconut Cake

Our Syria is a delicious celebration of the unique taste, culture, and food of Syria-and a celebration of everything that food and memory can mean to an individual, to a family, and to a nation.

-

"Like most Syrian dishes, the recipes in Our Syria are flavorful, scrumptious and healthy. You will tremendously enjoy making and eating these dishes if you like international and healthy food. If this is your first time eating Syrian dishes, you will become addicted to them."- The Washington Book Review

-

"Our Syria is laced with glorious food to nourish the body and bittersweet memories to salve the soul. The ancient splendors of Syrian culture may have been decimated, but thanks to these two culinary documentarians, its foodways are being preserved."- myAJC (blog)