Promotion

Use code MOM24 for 20% off site wide + free shipping over $45

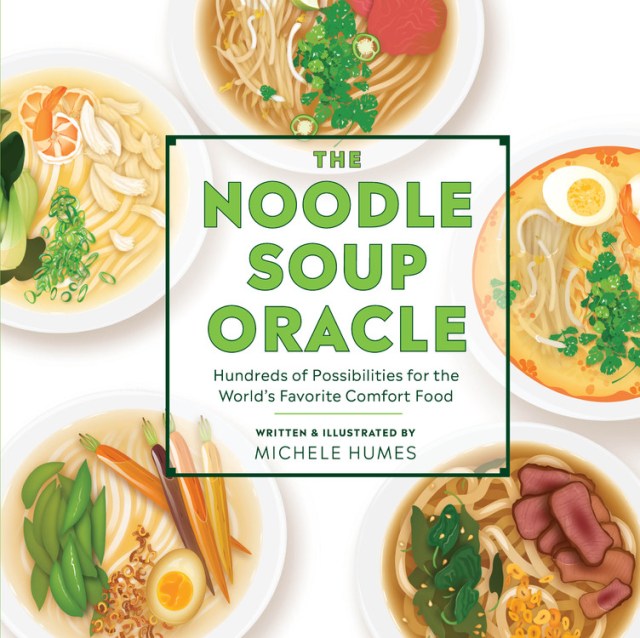

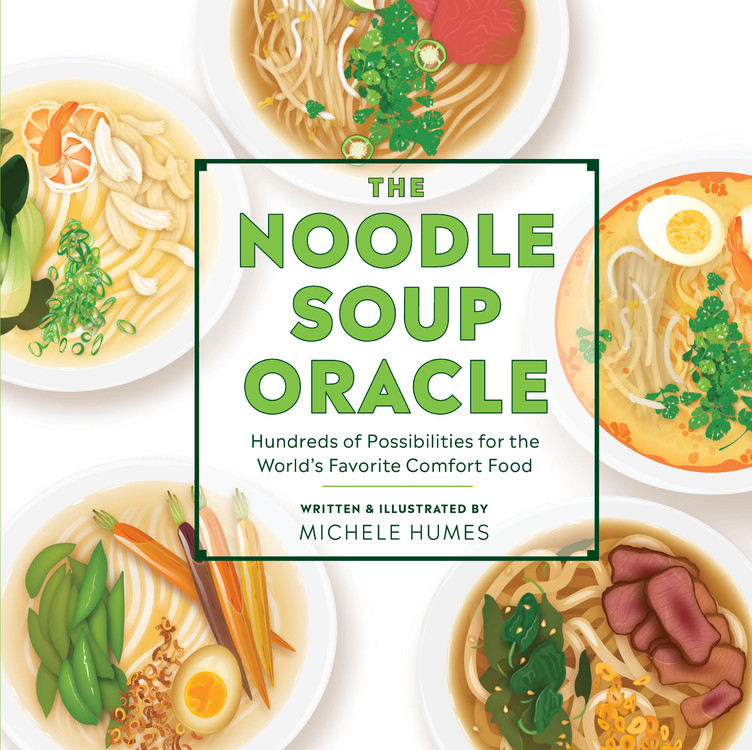

The Noodle Soup Oracle

Hundreds of Possibilities for the World's Favorite Comfort Food

Contributors

Formats and Prices

Price

$22.00Price

$28.00 CADFormat

Format:

- Hardcover $22.00 $28.00 CAD

- ebook $12.99 $15.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around October 8, 2019. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

This isn’t your traditional noodle soup cookbook. It’s a mix-and-match guide to building the dish you want to eat.

First, you’ll choose your noodle. Next, pick your soup, whether it’s a broth from scratch or one that starts from a box or can. Finally, decide on the proteins, vegetables, and flourishes that will give your bowl color and character-the Oracle will show you the best way to prep nearly any topping you can dream up.

Within these pages, you’ll find tried-and-true flavor combinations and start-to-finish bowl recipes, but they’re here to entice and inspire, not constrain. Add to them, subtract from them, and shatter the boundaries between ramen, saimin, and pho.

Genre:

- On Sale

- Oct 8, 2019

- Page Count

- 208 pages

- Publisher

- Running Press

- ISBN-13

- 9780762464579

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use