Promotion

Use code MOM24 for 20% off site wide + free shipping over $45

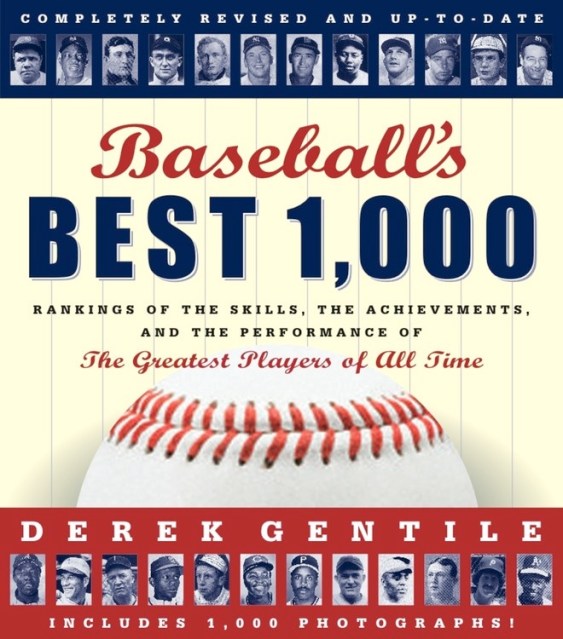

Baseball's Best 1000 -- Revised and Updated

Rankings of the Skills, the Achievements and the Performance of the Greatest Players of All Time

Contributors

Formats and Prices

Price

$9.99Price

$12.99 CADFormat

Format:

ebook $9.99 $12.99 CADThis item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around May 15, 2012. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

This thoroughly revised edition of “Baseball’s Best 1,000” includes updated listings plus new players, rankings, and photographs, all in a handier format that makes it a terrific pocket reference.

A must-have book for baseball fans obsessed with stats, quick facts, and the age-old debates over who the best players are and why, “Baseball’s Best 1,000” showcases the lives, legends, and lore of the game’s top players, ranked in order. Sportswriter Derek Gentile has pared down the total list of players–tens of thousands of them–to an elite ranking of the thousand greatest, based on criteria including lifetime stats; player durability and consistency; All-Star participation; MVP, Gold Glove, and Cy Young awards; individual statistical championships; personal and professional contributions to the game; sportsmanship; and election to the Hall of Fame.

Each entry includes positions played, teams played for, years played, lifetime stats, and a biography of the player featuring his great moments and little-known facts.

*New players include Curt Schilling, Mike Mussina, and Manny Ramirez.

*Barry Bonds has moved up from Number 19 to Number 6.

*Roger Clemens has moved from Number 33 into the top 20.

*Dozens of Negro League players are here, as well as rankings of the best Japanese players, women players, and “prehistoric” players (from the time before stats were formally recorded).

Genre:

- On Sale

- May 15, 2012

- Page Count

- 656 pages

- Publisher

- Black Dog & Leventhal

- ISBN-13

- 9781603763158

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use