By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

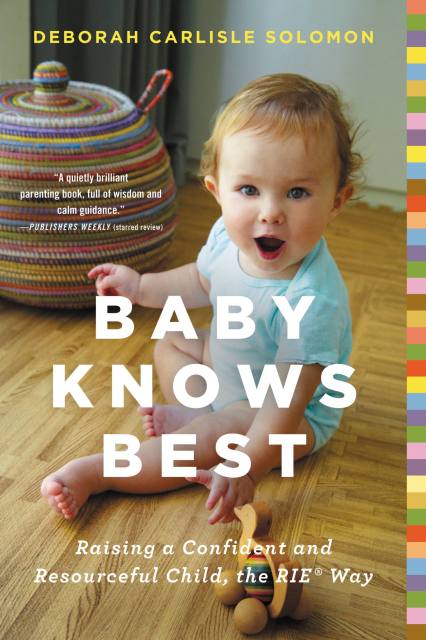

Baby Knows Best

Raising a Confident and Resourceful Child, the RIE™ Way

Contributors

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Dec 17, 2013

- Page Count

- 288 pages

- Publisher

- Little Brown Spark

- ISBN-13

- 9780316219211

Price

$9.99Price

$12.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $9.99 $12.99 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged)

- Trade Paperback $19.99 $25.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around December 17, 2013. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

Your baby knows more than you think. That’s the heart of the principles and teachings of Magda Gerber, founder of RIE (Resources for Infant Educarers), and Educaring. Baby Knows Best is based on Gerber’s belief in babies’ natural abilities to develop at their own pace, without coaxing from helicoptering or hovering parents. The Educaring Approach helps parents see their infants as competent people with a growing ability to communicate, problem-solve, and self-soothe.

Baby Knows Best is a comprehensive resource that shows parents how to respond to their babies’ cues and signals; how to develop healthy sleep habits; why babies need uninterrupted playtime; and how to set clear, consistent limits. The result? More relaxed parents and more confident, self-reliant children.

-

"The RIE program is the single most relatable, intuitive, and common sense approach to the modern day conundrum of parenting. Baby Knows Best is the guide book. It helps you get back to basics and makes you a better, more confident parent as you learn that Babies do indeed Know Best. A must-have on yours and your baby's library shelf." --Jamie Lee Curtis

-

"I think RIE should be a national program so that parents all over the country can have the opportunity that my family had." --Dee Dee Myers, former White House Press Secretary

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use