By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

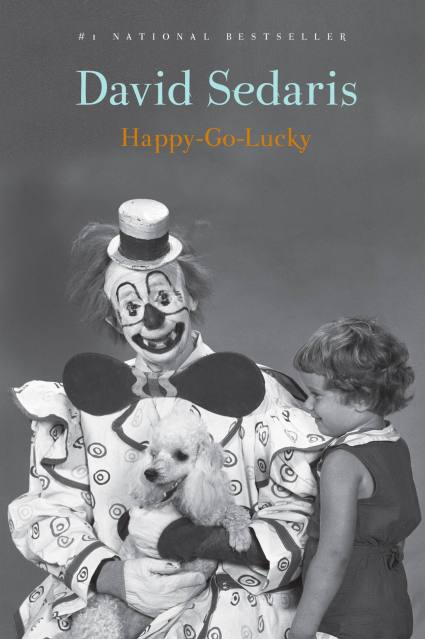

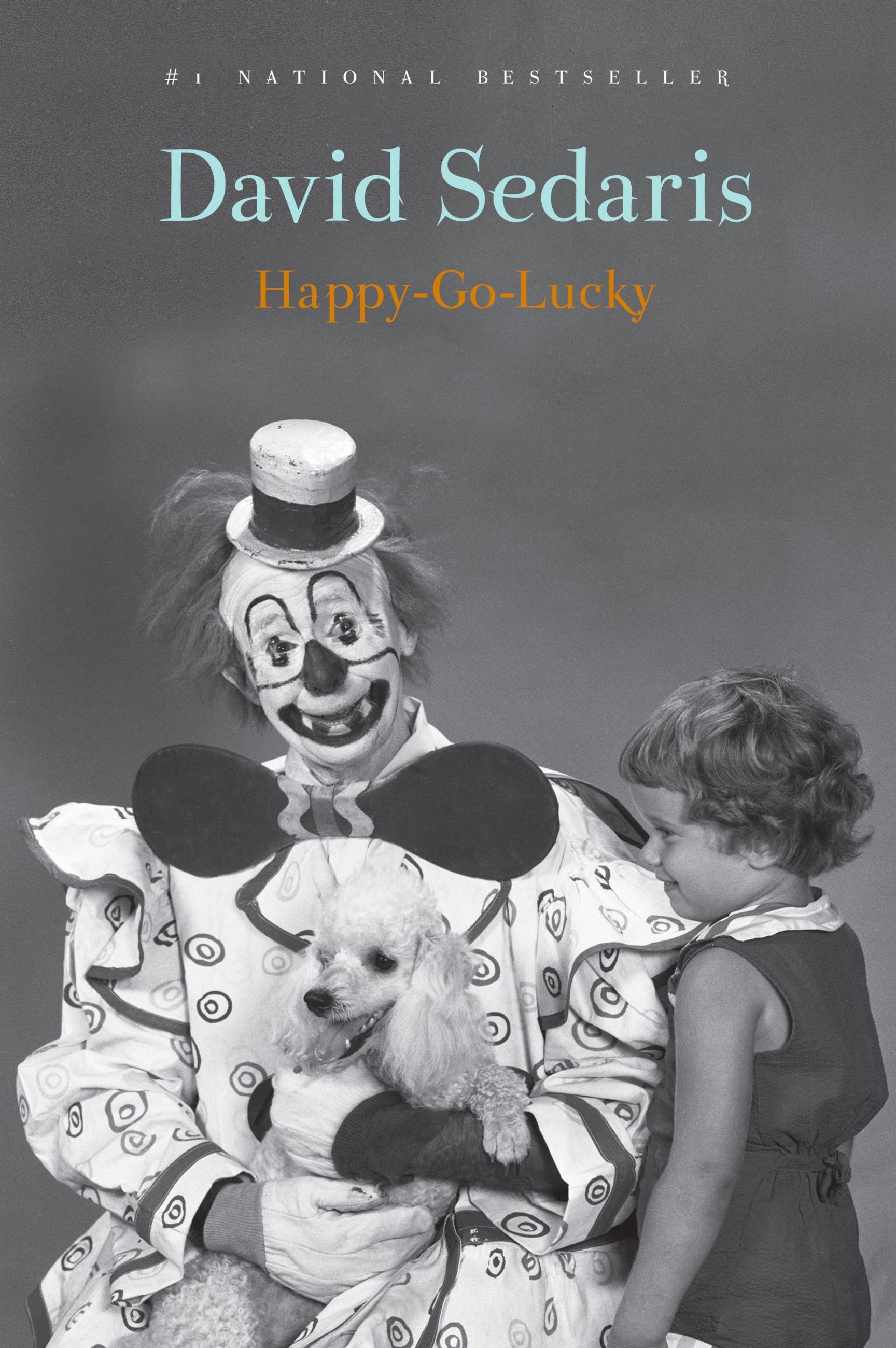

Happy-Go-Lucky

Contributors

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- May 31, 2022

- Page Count

- 400 pages

- Publisher

- Little, Brown and Company

- ISBN-13

- 9780316445412

Price

$31.00Price

$39.00 CADFormat

Format:

- Hardcover (Large Print) $31.00 $39.00 CAD

- ebook $11.99 $15.99 CAD

- Hardcover $29.00 $37.00 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged) $24.99

- Trade Paperback $19.99 $25.99 CAD

- Audiobook CD (Unabridged) $45.00 $57.00 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around May 31, 2022. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

David Sedaris, the “champion storyteller,” (Los Angeles Times) returns with his first new collection of personal essays since the bestselling Calypso

Back when restaurant menus were still printed on paper, and wearing a mask—or not—was a decision made mostly on Halloween, David Sedaris spent his time doing normal things. As Happy-Go-Lucky opens, he is learning to shoot guns with his sister, visiting muddy flea markets in Serbia, buying gummy worms to feed to ants, and telling his nonagenarian father wheelchair jokes.But then the pandemic hits, and like so many others, he’s stuck in lockdown, unable to tour and read for audiences, the part of his work he loves most. To cope, he walks for miles through a nearly deserted city, smelling only his own breath. He vacuums his apartment twice a day, fails to hoard anything, and contemplates how sex workers and acupuncturists might be getting by during quarantine.

As the world gradually settles into a new reality, Sedaris too finds himself changed. His offer to fix a stranger’s teeth rebuffed, he straightens his own, and ventures into the world with new confidence. Newly orphaned, he considers what it means, in his seventh decade, no longer to be someone’s son. And back on the road, he discovers a battle-scarred America: people weary, storefronts empty or festooned with Help Wanted signs, walls painted with graffiti reflecting the contradictory messages of our time: Eat the Rich. Trump 2024. Black Lives Matter.

In Happy-Go-Lucky, David Sedaris once again captures what is most unexpected, hilarious, and poignant about these recent upheavals, personal and public, and expresses in precise language both the misanthropy and desire for connection that drive us all. If we must live in interesting times, there is no one better to chronicle them than the incomparable David Sedaris.

Genre:

-

“Sublimely funny… Sedaris is back, doing the thing his readers have come to adore: offering up wry, moving, punchy stories about his oddball family… The pieces range widely, following the path of Sedaris’s travels and his eccentric mind, but a through line involves his nonagenarian father… This is one of the more complicated relationships of Sedaris’s life, and he is unflinching as he tries to understand who his enigmatic father was, and how living with him altered the shape of his own existence.”Gal Beckerman, The Atlantic

-

“Sedaris’ signature wit has always thrived on the macabre, so perhaps it should come as no surprise that Happy-Go-Lucky is some of his darkest—and most astute—writing yet… No topic is out of bounds for Sedaris’ acerbic humor and sharp observations.”Time

-

“Sedaris is funny—invariably. That’s his gift… Even amid the overwhelming gloom of the pandemic, a summer of unrest and the death of a father toward whom he still has complicated feelings, Sedaris never loses his wit or his crack timing.”Tyler Malone, Los Angeles Times

-

“Consistently funny… when you’re dealing with a talent as outsize as Sedaris’s, even the missteps are fairly negligible… Rather, the lasting impression of “Happy-Go-Lucky” is similar to that of Sedaris’s other books: It’s a neat trick that one writer’s preoccupation with the odd and the inappropriate can have such widespread appeal.”Henry Alford, New York Times Book Review

-

“Comically blistering… David Sedaris is the standard against which all other humor essayists are judged, the overwhelming heavyweight of the genre… Happy-Go-Lucky could serve as a textbook to readers dealing with the end times of their own parents with whom they don’t get along.”Brian Boone, Vulture

-

“A new collection of poignant, honest and funny essays… Sedaris is simultaneously amusing and brutal while unflinchingly exposing the ironies of his family and life in general.”Anita Snow, Associated Press

-

“Engaging… Sedaris recounts his lockdown experience with his customary blend of wry self-deprecation and affable misanthropy.”Houman Barekat, The Guardian

-

"Hilarious… much of Sedaris’ humor comes from saying the quiet parts out loud—writing frankly about things most of us never mention."Collette Bancroft, Tampa Bay Times

-

“Sedaris, a perennial contrarian, has entered into a comfortable late-middle age that could sink a less determined writer… Happily for Sedaris’s fans, it will take more than prosperity to mellow him out: His trademark black humor and puckish misanthropy remain.”James Tarmy, Bloomberg

-

“The older Sedaris gets, the funnier he gets—if you don’t mind your laugh out loud humor tempered with self-knowledge and compassion."Bethanne Patrick, Los Angeles Times

-

“Sedaris has long been frank about his lifelong disconnect with his father, but he has reflected more openly — and movingly — about it since his father reached his nineties… Happy-Go-Lucky is more somber than Sedaris' usual fare, but there are some fresh, funny bits wedged between the weighty boulders.”Heller McAlpin, NPR

-

“Happy-Go-Lucky is like a reminder of an old friend who can still make you laugh out loud, but with a poignance now.”Christopher Borrelli, Chicago Tribune

-

“Sedaris's many fans will be filling up reserve lists for a fresh infusion of his unique candor and comedy… though his tone is more poignant than pointed, the essential Sedaris humor reassuringly endures. Amid the barbed quips, there is genuine sorrow, an empathy born of arduous experience.”Carol Haggas, Booklist (starred review)

-

“A sweet-and-sour set of pieces on loss, absurdity, and places they intersect… Sedaris remains stubbornly irreverent even in the face of pandemic lockdowns and social upheaval.”Kirkus Reviews

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use