Promotion

Use code SPRING26 for 20% off sitewide.

By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

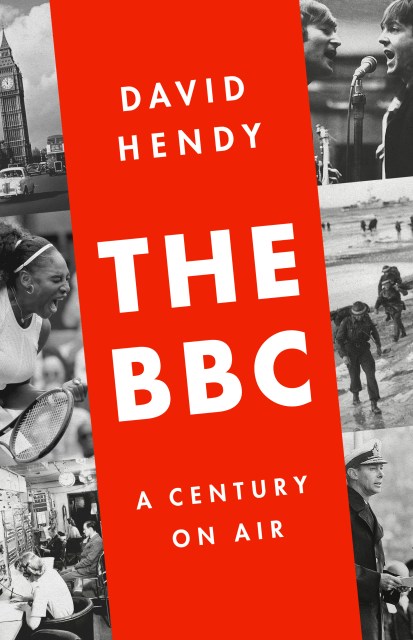

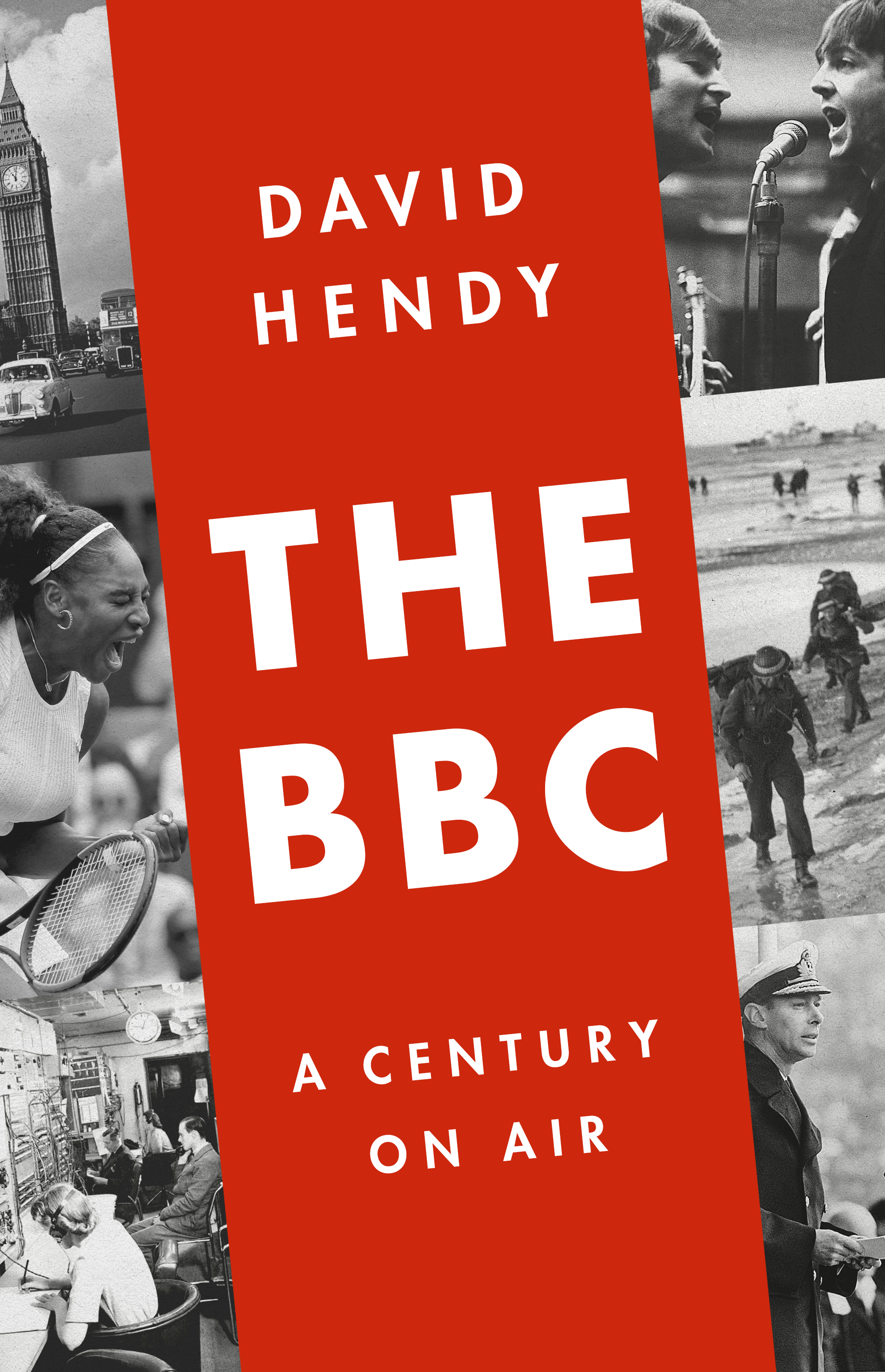

The BBC

A Century on Air

Contributors

By David Hendy

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Mar 29, 2022

- Page Count

- 656 pages

- Publisher

- PublicAffairs

- ISBN-13

- 9781610397056

Price

$19.99Price

$25.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $19.99 $25.99 CAD

- Hardcover $38.00 $48.00 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around March 29, 2022. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

The first in-depth history of the iconic radio and TV network that has shaped our past and present.

Doctor Who; tennis from Wimbledon; the Beatles and the Stones; the coronation of Queen Elizabeth and the funeral of Diana, Princess of Wales: for one hundred years, the British Broadcasting Corporation has been the preeminent broadcaster in the UK and around the world, a constant source of information, comfort, and entertainment through both war and peace, feast and famine.

The BBC has broadcast to over two hundred countries and in more than forty languages. Its history is a broad cultural panorama of the twentieth century itself, often, although not always, delivered in a mellifluous Oxford accent. With special access to the BBC’s archives, historian David Hendy presents a dazzling portrait of a unique institution whose cultural influence is greater than any other media organization.

Mixing politics, espionage, the arts, social change, and everyday life, The BBC is a vivid social history of the organization that has provided both background commentary and screen-grabbing headlines—woven so deeply into the culture and politics of the past century that almost none of us has been left untouched by it.

-

“Much of this history has been told before but never in such well-researched depth and sparkling detail…An appropriately large-scale account of the media giant at the very heart of British life."Kirkus

-

“[A] highly readable, at times gripping, history of the BBC…I found much that was striking and new… a fascinating and informative account of the BBC’s first 100 years.”The Telegraph

-

“[E]ngaging and fair… It is very much the case for the BBC, but it is a case which, with things as they are, needs to be made; and Hendy makes it well.”The Scotsman

-

“Hendy…set[s] the scene rather well of these three influential figures at the dawning of what would turn out to be this country’s biggest and most significant cultural institution.”The Observer (UK)

-

“Hendy's lively new history is a reminder that the BBC 's present struggles—government rows, culture wars, foreign rivals and more—are modern manifestations of old problems. His account of the corporation also makes for an incisive history of Britain's 20th century.”The Economist

-

"The author knows what he is doing, and has quietly and elegantly written a book which is nothing short of a nonfiction thriller. Hendy takes a controversial subject and with riveting anecdotes offers a forensic cross-examination of BBC executives and their political adversaries. There are enough showdowns in this account to satisfy any Gunsmoke aficionado, with firings and resignations taking the place of gunfights."AirMail

-

“[A] deep and informative core reading of the BBC’s first 100 years. With bright thumbnails on key figures and entertaining vignettes on memorable moments, The BBC sheds considerable light on the history of a leading broadcaster.”New York Journal of Books

-

“[T]horough and engaging.”Dwight Garner, The New York Times

-

“David Hendy’s book has the strengths of an insider’s account, packed with detail and anecdotes, shrewd in its assessment of personalities, light on socioeconomic change.”London Review of Books

-

“Hendy is the more gifted writer, with an eye for amusing details and an ear for the voices of performers and program-makers… Hendy’s more writerly instinct for a telling anecdote makes the BBC’s war the best section of his engaging book—but then the wartime material itself reflects a high point for the corporation.”Matt Seaton, New York Review of Books, and Simon Potter, This is the BBC