Promotion

Use code SPRING26 for 20% off sitewide.

By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

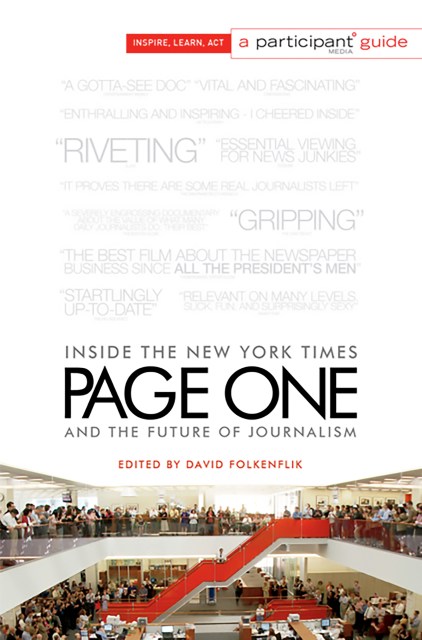

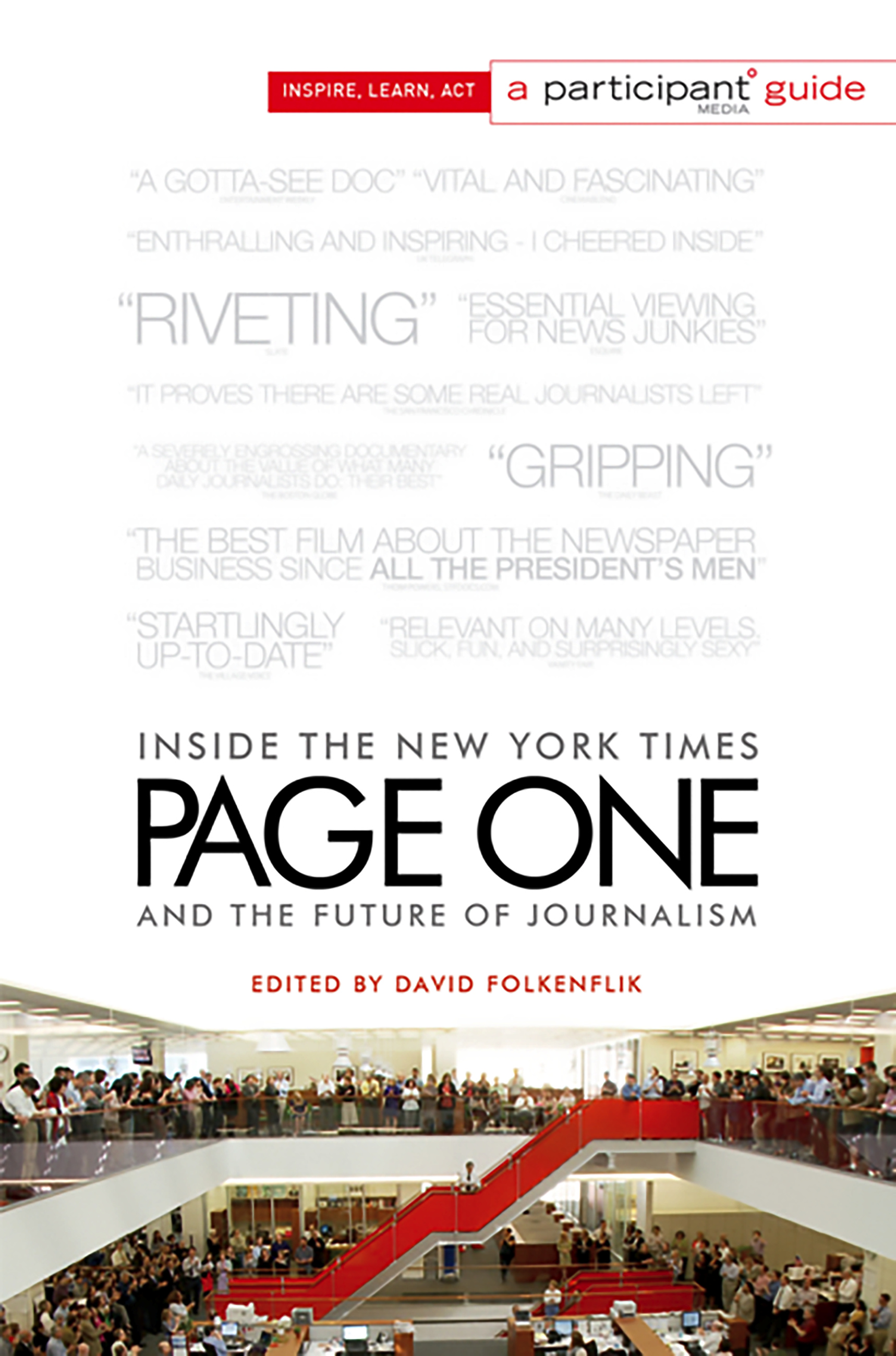

Page One

Inside The New York Times and the Future of Journalism

Contributors

By Participant

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Jun 28, 2011

- Page Count

- 208 pages

- Publisher

- PublicAffairs

- ISBN-13

- 9781586489601

Price

$15.99Price

$18.50 CADFormat

Format:

- Trade Paperback $15.99 $18.50 CAD

- ebook $9.99 $12.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around June 28, 2011. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

Expanding on Andrew Rossi’s “riveting” film (Slate), David Folkenflik has convened some of the smartest media savants to talk about the present and the future of news. Behind all the debate is the presence of the New York Times, and the inside story of its attempt to navigate the new world, embracing the immediacy of the web without straying from a commitment to accurate reporting and analysis that provides the paper with its own definition of what it is there to showcase: all the news that’s fit to print.

-

Philadelphia Review of Books“Folkenflik’s book brings important topics like digitization, collaboration and new economic models to light.”