Promotion

Use code SPRING26 for 20% off sitewide.

By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

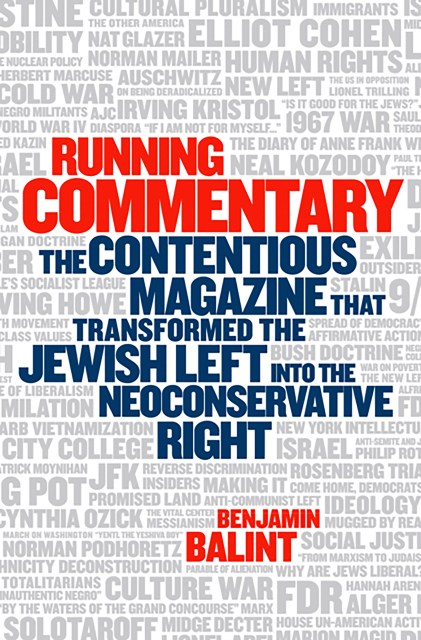

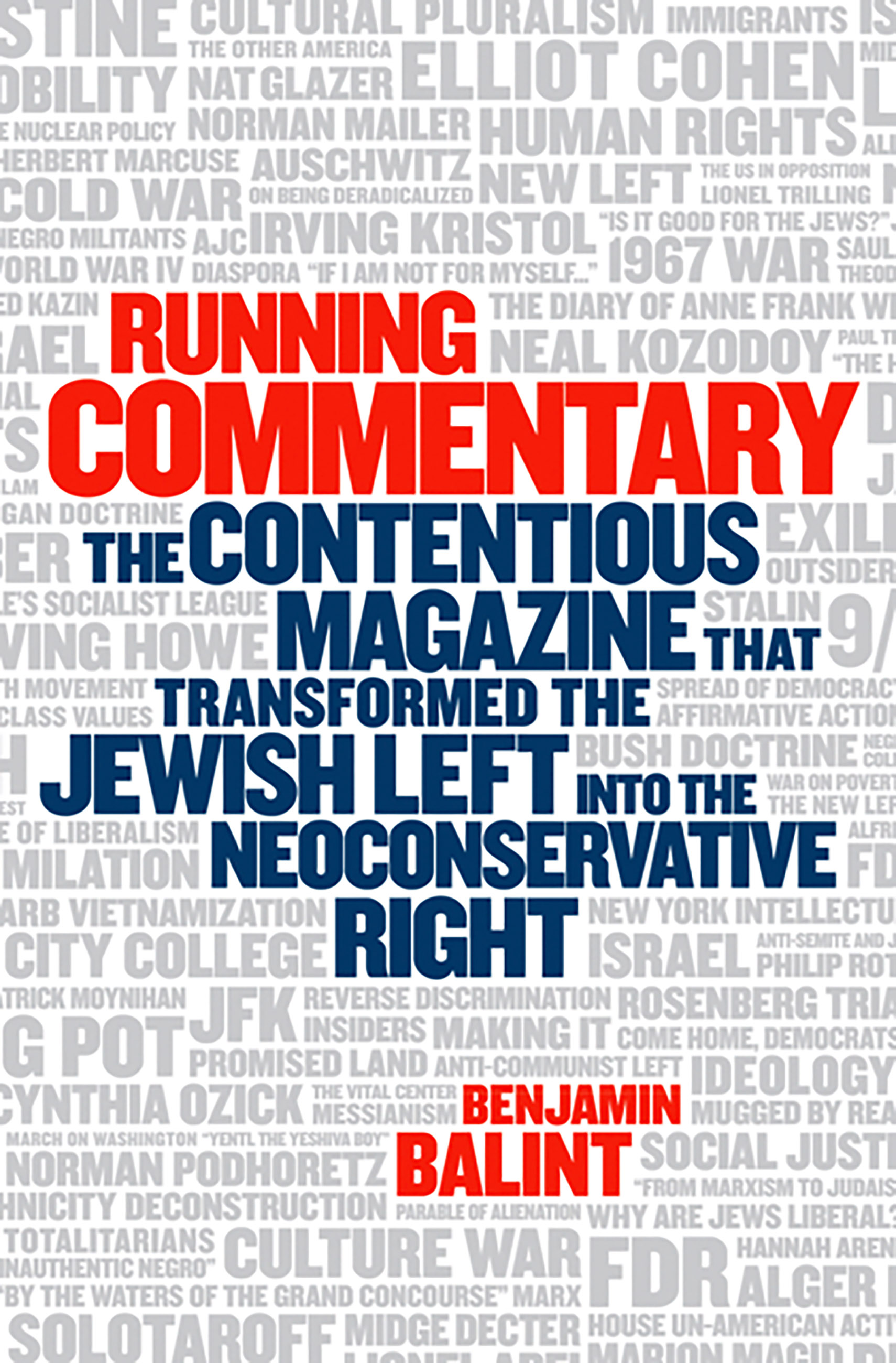

Running Commentary

The Contentious Magazine that Transformed the Jewish Left into the Neoconservative Right

Contributors

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Jun 1, 2010

- Page Count

- 304 pages

- Publisher

- PublicAffairs

- ISBN-13

- 9781586488604

Price

$17.99Price

$22.99 CADFormat

Format:

ebook $17.99 $22.99 CADThis item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around June 1, 2010. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

Founded by the offspring of immigrants, Commentary began life as a voice for the marginalized and a feisty advocate for civil rights and economic justice. But just as American culture moved in its direction, it began — inexplicably to some — to veer right, becoming the voice of neoconservativism and defender of the powerful.

This lively history, based on unprecedented access to the magazine’s archives and dozens of original interviews, provocatively explains that shift while recreating the atmosphere of some of the most exciting decades in American intellectual life.