Promotion

Use code MOM24 for 20% off site wide + free shipping over $45

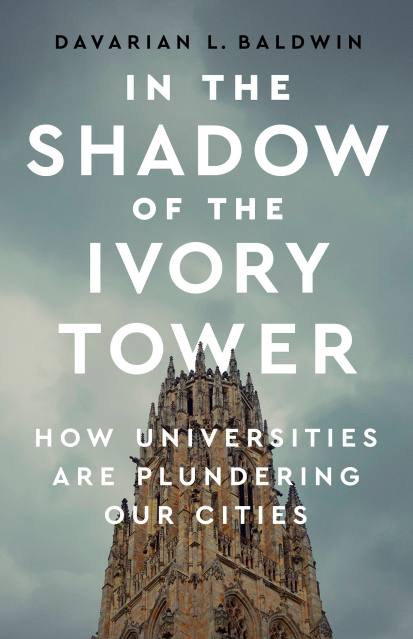

In the Shadow of the Ivory Tower

How Universities Are Plundering Our Cities

Contributors

Formats and Prices

Price

$16.99Price

$21.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $16.99 $21.99 CAD

- Hardcover $29.00 $37.00 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged) $24.99

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around March 30, 2021. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

Urban universities play an outsized role in America’s cities. They bring diverse ideas and people together and they generate new innovations. But they also gentrify neighborhoods and exacerbate housing inequality in an effort to enrich their campuses and attract students. They maintain private police forces that target the Black and Latinx neighborhoods nearby. They become the primary employers, dictating labor practices and suppressing wages.

In the Shadow of the Ivory Tower takes readers from Hartford to Chicago and from Phoenix to Manhattan, revealing the increasingly parasitic relationship between universities and our cities. Through eye-opening conversations with city leaders, low-wage workers tending to students’ needs, and local activists fighting encroachment, scholar Davarian L. Baldwin makes clear who benefits from unchecked university power—and who is made vulnerable.

In the Shadow of the Ivory Tower is a wake-up call to the reality that higher education is no longer the ubiquitous public good it was once thought to be. But as Baldwin shows, there is an alternative vision for urban life, one that necessitates a more equitable relationship between our cities and our universities.

Genre:

- On Sale

- Mar 30, 2021

- Page Count

- 288 pages

- Publisher

- Bold Type Books

- ISBN-13

- 9781568588919

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use