Promotion

Use code MOM24 for 20% off site wide + free shipping over $45

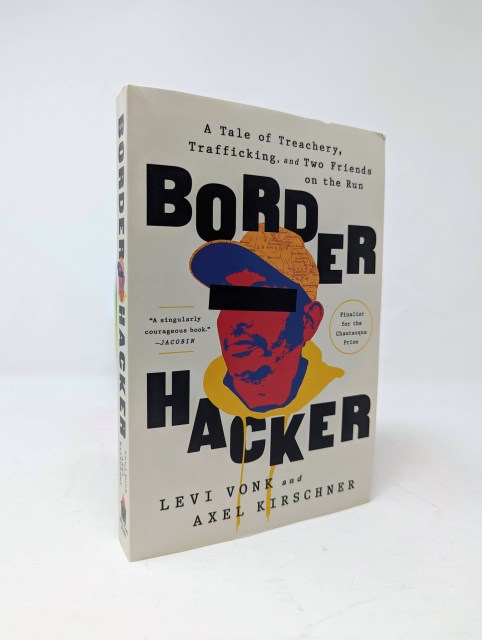

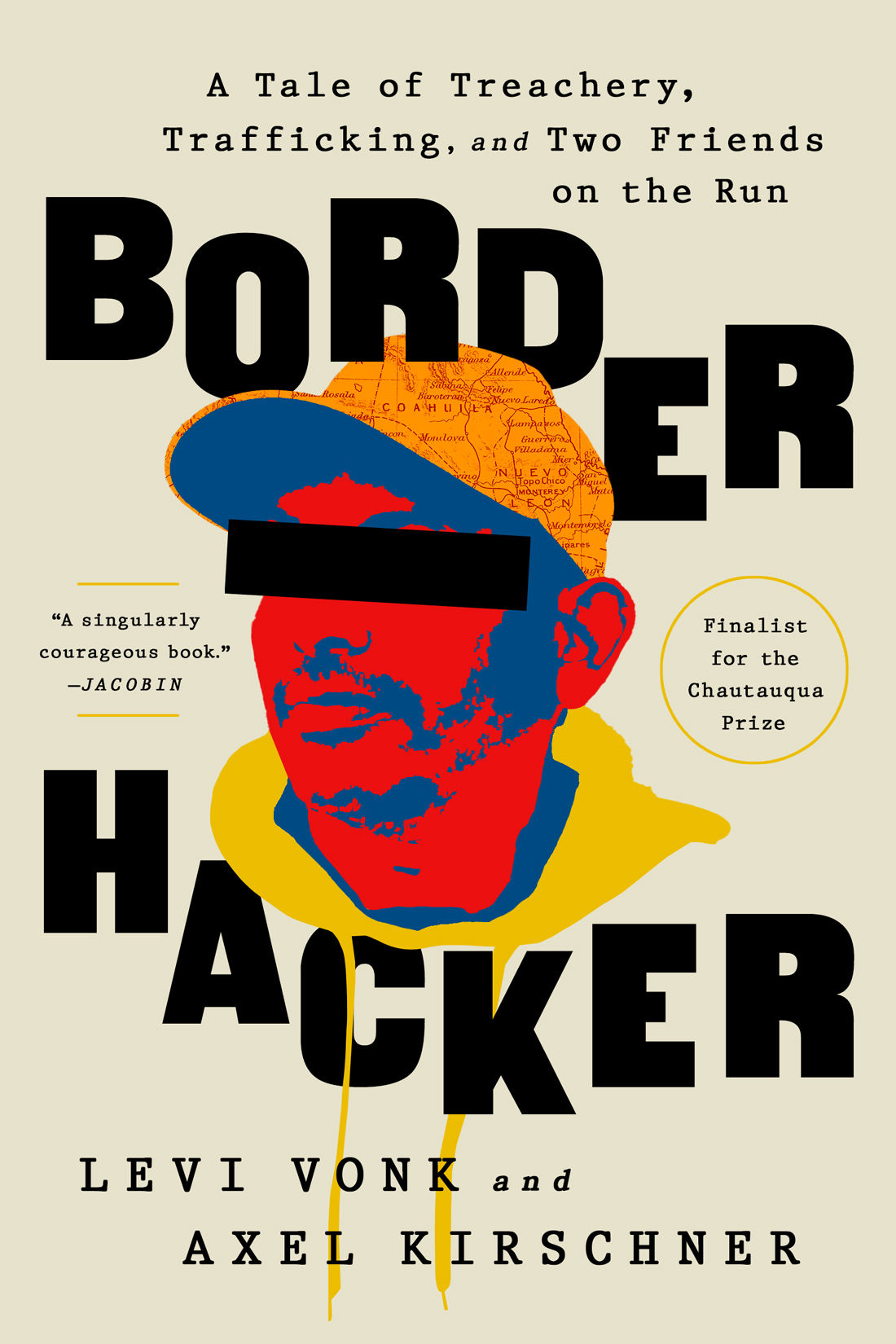

Border Hacker

A Tale of Treachery, Trafficking, and Two Friends on the Run

Contributors

By Levi Vonk

Formats and Prices

Price

$19.99Price

$25.99 CADFormat

Format:

- Trade Paperback $19.99 $25.99 CAD

- ebook $17.99 $22.99 CAD

- Hardcover $29.00 $37.00 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged) $27.99

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around October 3, 2023. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

An unlikely friendship, a four-thousand-mile voyage, and an impenetrable frontier—this dramatic odyssey reveals the chaos and cruelty US immigration policies have unleashed beyond our borders.

Axel Kirschner was a lifelong New Yorker, all Queens hustle and bravado. But he was also undocumented. After a minor traffic violation while driving his son to kindergarten, Axel was deported to Guatemala, a country he swore he had not lived in since he was a baby. While fighting his way back through Mexico on a migrant caravan, Axel met Levi Vonk, a young anthropologist and journalist from the US. That chance encounter would change both of their lives forever.

Levi soon discovered that Axel was no ordinary migrant. He was harboring a secret: Axel was a hacker. This secret would launch the two friends on a dangerous adventure far beyond what either of them could have imagined. While Axel’s abilities gave him an edge in a system that denied his existence, they would also ensnare him in a tangled underground network of human traffickers, corrupt priests, and anti-government guerillas eager to exploit his talents for their own ends. And along the way, Axel’s secret only raised more questions for Levi about his past. How had Axel learned to hack? What did he want? And was Axel really who he said he was?

Border Hacker is at once an adventure saga—the story of a man who would do anything to return to his family, and the friend who would do anything to help him—and a profound parable about the violence of American immigration policy told through a single, extraordinary life.

Genre:

-

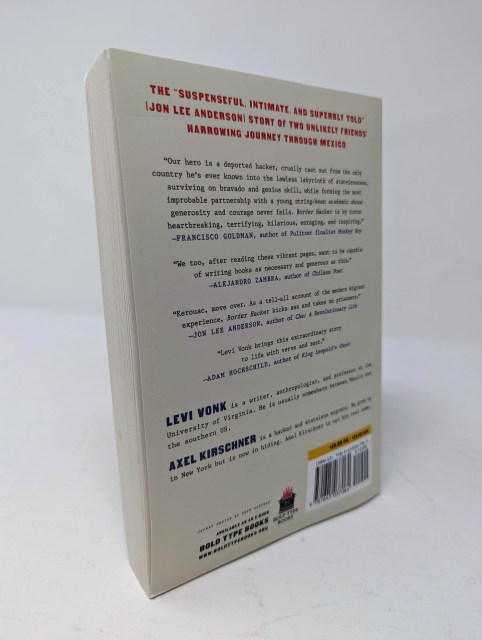

“If this book were a novel, you’d say it was too implausible: an unlikely friendship, a dangerous journey, an apparent benefactor who turns out to be the opposite. But it’s all true, and Levi Vonk brings this extraordinary story to life with verve and zest.” Adam Hochschild, author of King Leopold’s Ghost

-

“Our twenty-first-century American hero is a deported hacker, cruelly cast out from the only country he’s ever known into the lawless labyrinth of statelessness, surviving on bravado and genius skill, while forming the most improbable partnership with a young string-bean ‘cracker’ academic whose generosity and courage never fails—and whose initial naivete is honed on this journey into the knowing, thoughtful voice of the chronicler of this book. Border Hacker is by turns heartbreaking, terrifying, hilarious, enraging, and inspiring. To say it humanizes contentious issues is a profound understatement.”Francisco Goldman, author of Monkey Boy

-

“Jack Kerouac, move over. In Border Hacker, Levi Vonk and Axel Kirschner’s unlikely friendship makes for the ultimate on-the-road buddy story. Suspenseful, intimate, and superbly told, Border Hacker is an amazing book, and as a tell-all account of the modern migrant experience, it kicks ass and takes no prisoners.”Jon Lee Anderson, author of Che: A Revolutionary Life

-

“Combining Vonk’s in-depth reportage on U.S. border policy, predatory shelter operators, and the links between cartels, kidnappers, and the police with Kirschner’s first-person testimony, the two unspool a riveting and disturbing story. Readers will be aghast.”Publishers Weekly

-

“An inspiring, timely border story…a significant addition to the literature on an ongoing humanitarian crisis…An engaging work of on-the-ground journalism that exposes root causes of a chronic problem.”Kirkus Reviews

-

“Axel and Levi are likable characters, which makes rooting for them easy. This is a cultural anthropology story that’s well-told and eminently readable.”The Bibliophage

-

“[A] thrilling, troubling, and wholly unique hybrid of confessional memoir and intrepid reportage…Border Hacker documents the phenomenon of migrant caravanning in the Americas more ably than any other book to my knowledge…is a singularly courageous book.”Jacobin

-

“[T]he importance of Border Hacker is not in its allegations of activists’ wrongdoing but in its illustration of the material and bureaucratic challenges of moving through Mexico, which incentivize all sorts of grift.”The Nation

-

“We too, after reading these vibrant pages, want to be capable of writing books as necessary and generous as this.”Alejandro Zambra, author of Chilean Poet

- On Sale

- Oct 3, 2023

- Page Count

- 352 pages

- Publisher

- Bold Type Books

- ISBN-13

- 9781645037064

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use