Promotion

Use code SPRING26 for 20% off sitewide.

By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

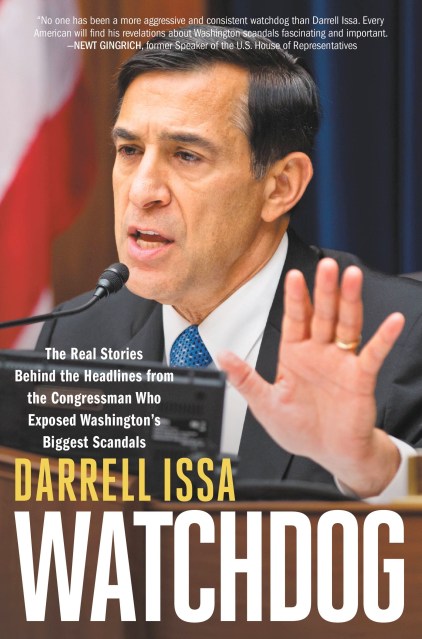

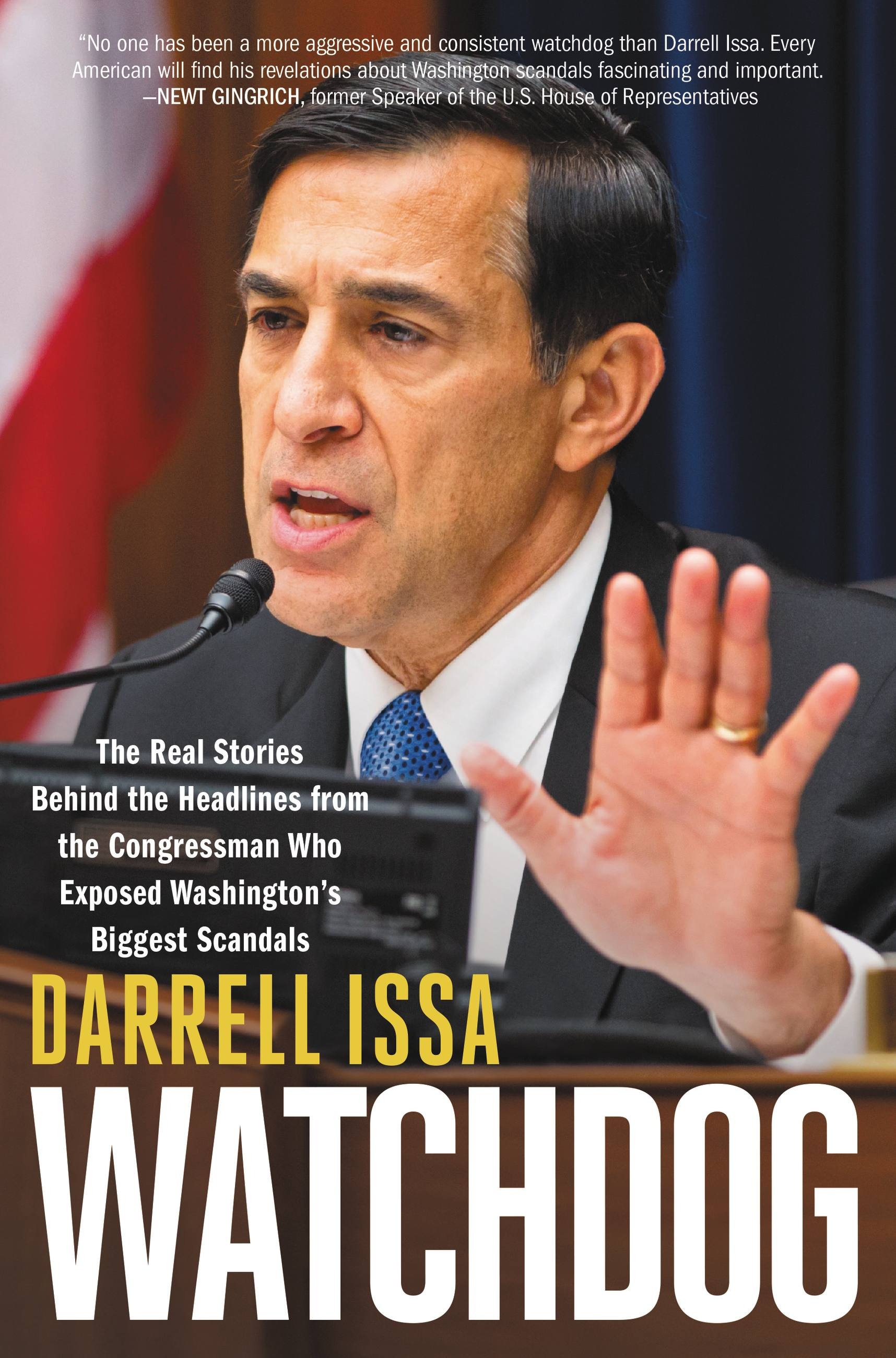

Watchdog

The Real Stories Behind the Headlines from the Congressman Who Exposed Washington's Biggest Scandals

Contributors

By Darrell Issa

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Jul 12, 2016

- Page Count

- 256 pages

- Publisher

- Center Street

- ISBN-13

- 9781455591985

Price

$36.00Price

$46.00 CADFormat

Format:

- Hardcover $36.00 $46.00 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged)

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around July 12, 2016. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

In Watchdog, Congressman Darrell Issa reveals some of the worst of Washington, pulls back the curtain on business as usual in the Capitol, and lets in the sunshine of accountability.

As Chairman of the Committee on Oversight and Government Reform, Issa led a years-long fight to uncover what was really happening in the Obama Administration and Hillary Clinton’s State Department, while taking on a mainstream media and establishment Beltway culture he quickly found out weren’t always interested in the truth.

But what the public doesn’t know about Big Government and what the people may not realize is happening to their country requires someone in Washington willing to tell the truth no matter who gets the blame.

Carrying out aggressive oversight brought Issa into conflict with not only political foes, but friends and allies as well. Through it all, he has sought to remind everyone in government they are still subject to the rule of law and accountable to the American people. Watchdog is the inside account of what it took to get the truth and what it will take for our democracy to endure.