By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

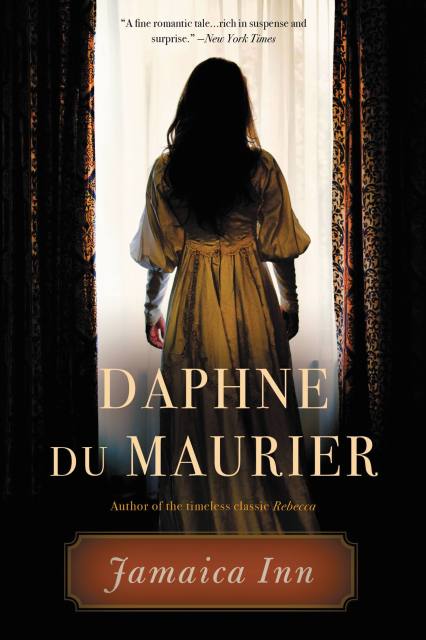

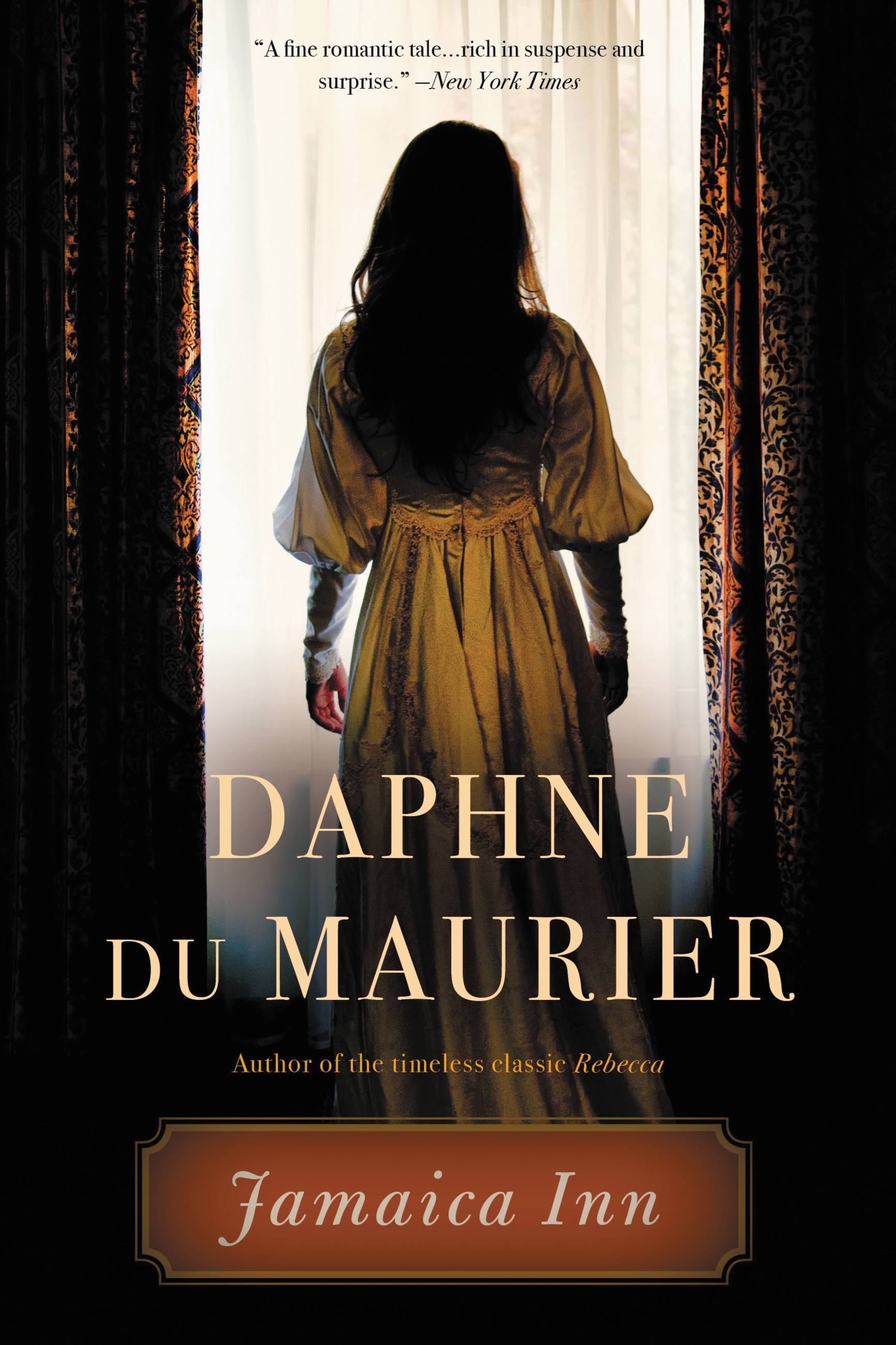

Jamaica Inn

Contributors

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Sep 5, 2023

- Page Count

- 320 pages

- Publisher

- Back Bay Books

- ISBN-13

- 9780316575225

Price

$19.99Format

Format:

Trade Paperback $19.99This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around September 5, 2023. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

On a bitter November evening, young Mary Yellan journeys across the rainswept moors to Jamaica Inn in honor of her mother’s dying request. When she arrives, the warning of the coachman begins to echo in her memory, for her aunt Patience cowers before hulking Uncle Joss Merlyn. Terrified of the inn’s brooding power, Mary gradually finds herself ensnared in the dark schemes being enacted behind its crumbling walls — and tempted to love a man she dares not trust.

The inspiration for the 1939 Alfred Hitchcock film.

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use