Promotion

Use code SPRING26 for 20% off sitewide.

By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

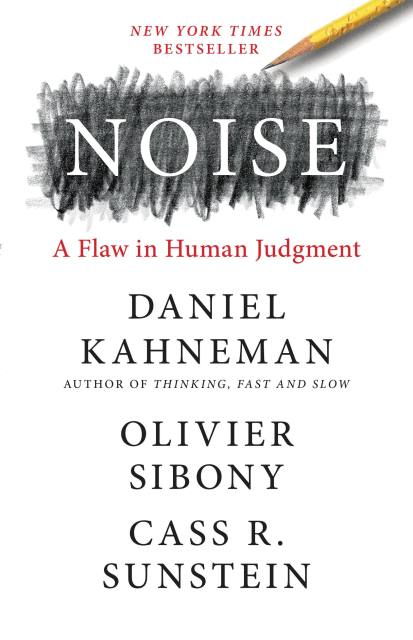

Noise

A Flaw in Human Judgment

Contributors

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- May 18, 2021

- Page Count

- 464 pages

- Publisher

- Little Brown Spark

- ISBN-13

- 9780316451406

Price

$32.00Price

$40.00 CADFormat

Format:

- Hardcover $32.00 $40.00 CAD

- ebook $12.99 $16.99 CAD

- Hardcover (Large Print) $34.00 $43.00 CAD

- Trade Paperback $24.99 $32.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around May 18, 2021. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

From the Nobel Prize-winning author of Thinking, Fast and Slow and the coauthor of Nudge, a revolutionary exploration of why people make bad judgments and how to make better ones—”a tour de force” (New York Times).

Imagine that two doctors in the same city give different diagnoses to identical patients—or that two judges in the same courthouse give markedly different sentences to people who have committed the same crime. Suppose that different interviewers at the same firm make different decisions about indistinguishable job applicants—or that when a company is handling customer complaints, the resolution depends on who happens to answer the phone. Now imagine that the same doctor, the same judge, the same interviewer, or the same customer service agent makes different decisions depending on whether it is morning or afternoon, or Monday rather than Wednesday. These are examples of noise: variability in judgments that should be identical.

In Noise, Daniel Kahneman, Olivier Sibony, and Cass R. Sunstein show the detrimental effects of noise in many fields, including medicine, law, economic forecasting, forensic science, bail, child protection, strategy, performance reviews, and personnel selection. Wherever there is judgment, there is noise. Yet, most of the time, individuals and organizations alike are unaware of it. They neglect noise. With a few simple remedies, people can reduce both noise and bias, and so make far better decisions.

Packed with original ideas, and offering the same kinds of research-based insights that made Thinking, Fast and Slow and Nudge groundbreaking New York Times bestsellers, Noise explains how and why humans are so susceptible to noise in judgment—and what we can do about it.

-

“The gold standard for a behavioral science book is to offer novel insights, rigorous evidence, engaging writing, and practical applications. It’s rare for a book to cover more than two of those bases, but Noise rounds all four—it’s a home run. Get ready for some of the world’s greatest minds to help you rethink how you evaluate people, make decisions, and solve problems.”Adam Grant, author of Think Again and host of the TED podcast WorkLife

-

"Noise completes a trilogy that started with Thinking, Fast and Slow and Nudge. Together, they highlight what all leaders need to know to improve their own decisions, and more importantly, to improve decisions throughout their organizations. Noise reveals a critical lever for improving decisions, not captured in much of the existing behavioral economics literature. I encourage you to read Noise soon, before noise destroys more decisions in your organization."Max H. Bazerman, author of Better, Not Perfect

-

“The influence of Noise should be seismic, as it explores a fundamental yet grossly underestimated peril of human judgment. Deepening its must-read status, it provides accessible methods for reducing the decisional menace.”Robert Cialdini, author of Influence and Pre-Suasion

-

“Choices matter. Unfortunately, many of the choices people make are fundamentally flawed by the presence of noise, the subject of this absolutely fascinating and essential book. It is deeply researched, thoughtful, and accessible. I began it with a sense of intrigue and concluded it with a sense of celebration. We can make better choices in business, politics, and our personal lives. This book lights the way.”Rita McGrath, author of Seeing Around Corners

-

"Brilliant! Noise goes deep on an under-appreciated source of error in human judgment: randomness. The story of noise has lacked the charisma of the story of cognitive bias…until now. Kahneman, Sibony, and Sunstein bring noise to life, making a compelling case for why we should take random variation in human judgment as seriously as we do bias and offering practical solutions for reducing noise (and bias) in judgment."Annie Duke, author of Thinking in Bets

-

"Noise may be the most important book I've read in more than a decade. A genuinely new idea so exceedingly important you will immediately put it into practice. A masterpiece."Angela Duckworth, author of Grit

-

"In Noise, the authors brilliantly apply their unique and novel insights into the flaws in human judgment to every sphere of human endeavor: from moneyball coaches to central bankers to military commanders to heads of state. Noise is a masterful achievement and a landmark in the field of psychology."Philip E. Tetlock, coauthor of Superforecasting

-

“The earth has been so fully explored that scientists can’t possibly discover a previously unknown mammal the size of an elephant. The same could be said about the landscape of decision-making, yet Kahneman, Sibony, and Sunstein have discovered a problem as large as an elephant: noise. In this important book they show us why noise matters, why there’s so much more of it than we realize, and how to reduce it. Implementing their advice would give us more profitable businesses, healthier citizens, a fairer legal system, and happier lives.”Jonathan Haidt, NYU Stern School of Business

-

"Noise is an absolutely brilliant investigation of a massive societal problem that has been hiding in plain sight."Steven Levitt, coauthor of Freakonomics

-

"A tour de force of scholarship and clear writing."New York Times

-

“Well-researched, convincing and practical book . . . written by the all-star team . . . The details and evidence will satisfy rigorous and demanding readers, as will the multiple viewpoints it offers on noise. Every academic, policymaker, leader and consultant ought to read this book. People with the power and persistence required to apply the insights in Noise will make more humane and fair decisions, save lives, and prevent time, money and talent from going to waste.”Robert Sutton, Washington Post

-

"Convincing...A humbling lesson in inaccuracy."Financial Times