Promotion

Use code MOM24 for 20% off site wide + free shipping over $45

Lincoln's Notebooks

Letters, Speeches, Journals, and Poems

Contributors

Edited by Dan Tucker

Foreword by Harold Holzer

Formats and Prices

Price

$19.99Price

$25.99 CADFormat

Format:

- Trade Paperback $19.99 $25.99 CAD

- ebook $12.99 $16.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around August 8, 2017. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

In addition to being one of the most admired and successful politicians in history, Abraham Lincoln was also a gifted writer whose speeches, eulogies, and addresses are both quoted often and easily recognizable all around the world.

Arranged chronologically into topics such as family and friends, the law, politics and the presidency, story-telling, religion, and morality, Lincoln’s Notebooks includes his famous letters to Ulysses S. Grant, Horace Greeley, and Henry Pierce, as well as personal letters to Mary Todd Lincoln and his note to Mrs. Bixby, the mother who lost five sons during the Civil War. Also included are full texts of the Gettysburg Address, the Emancipation Proclamation, both of Lincoln’s inaugural addresses, and his famous “A House Divided” speech. Additionally, rarely seen writings like poetry he composed as teenager give insight into Lincoln’s personality and private life.

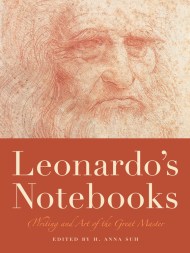

Richly illustrated with seventy-five photographs, facsimiles of letters, and more, plus commentary throughout by Dan Tucker and a foreword by Lincoln expert Harold Holzer, Lincoln’s Notebooks is an intimate look at this esteemed historical figure.

Genre:

- On Sale

- Aug 8, 2017

- Page Count

- 256 pages

- Publisher

- Black Dog & Leventhal

- ISBN-13

- 9780316389891

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use