By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

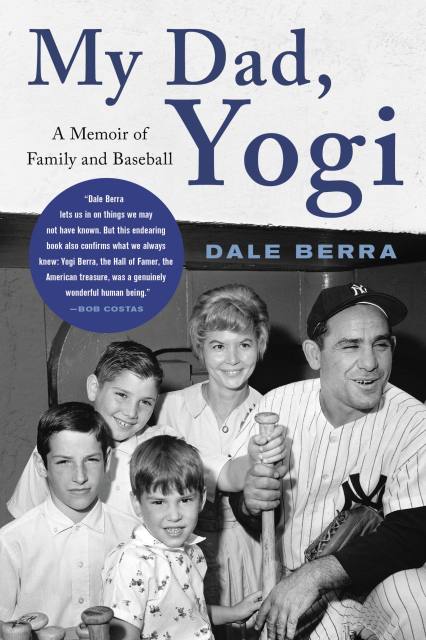

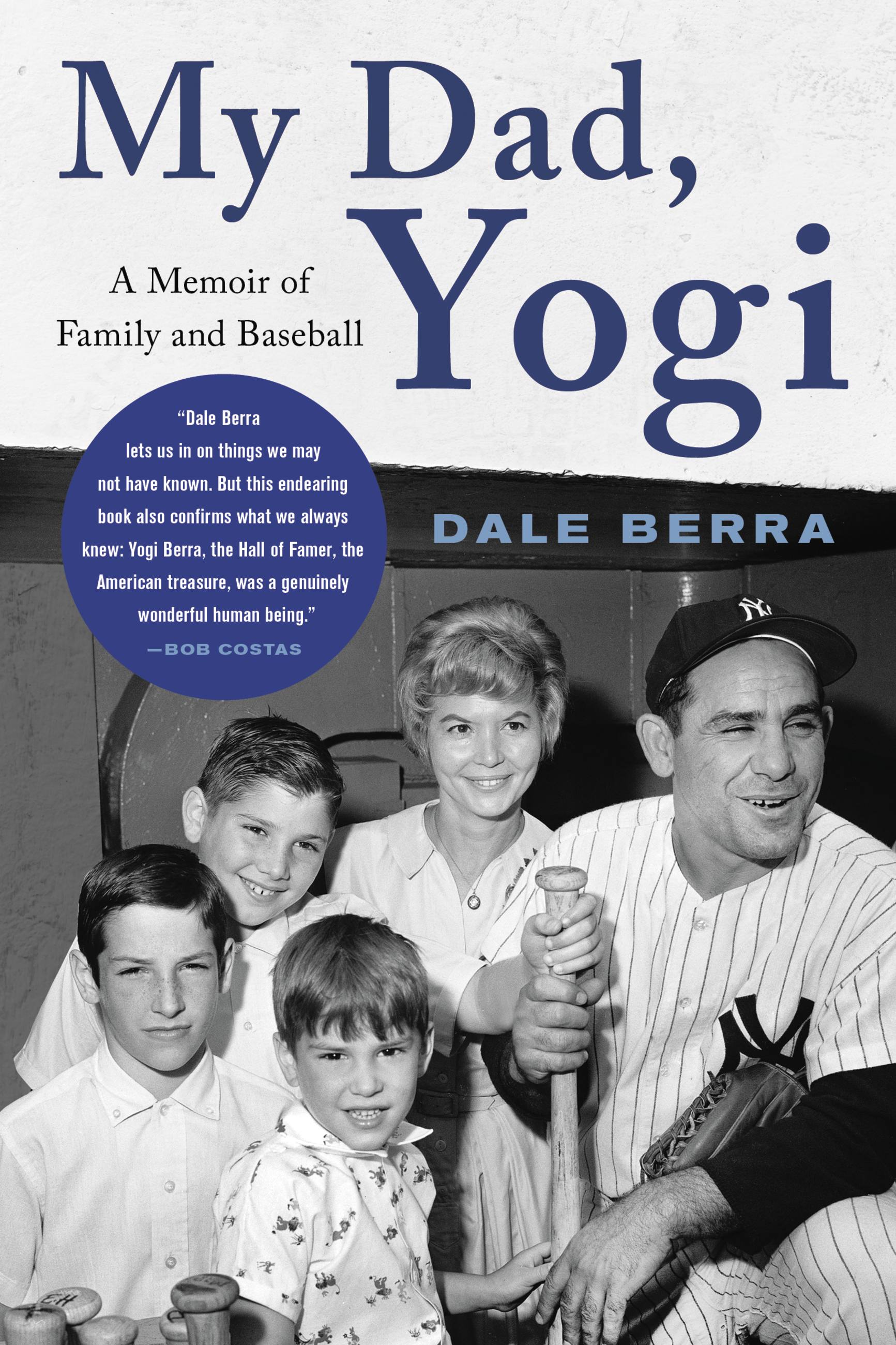

My Dad, Yogi

A Memoir of Family and Baseball

Contributors

By Dale Berra

With Mark Ribowsky

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- May 7, 2019

- Page Count

- 256 pages

- Publisher

- Grand Central Publishing

- ISBN-13

- 9780316525466

Price

$10.99Price

$13.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $10.99 $13.99 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged) $24.99

- Trade Paperback $15.99 $21.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around May 7, 2019. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

In this nostalgic memoir, a son provides a unique perspective on his legendary father–the baseball star, Yogi Berra.

Yogi Berra was the backbone of the New York Yankees through ten World Series Championships. In My Dad, Yogi is Dale Berra chronicles his unshakeable bond with his father, going back to his suburban New Jersey upbringing, his parents’ enduring relationship, and his Dad’s formidable career.

Following in his Dad’s footsteps, Dale came up with the Pittsburgh Pirates, contributing to their 1979 championship season and emerging as one of baseball's most talented young players before eventually uniting with his Dad in the Yankee dugout.

Yogi supported his son throughout his highs of his careers and lows of a drug addiction, eventually staging an intervention that would save Dale's life, and draw the entire family even closer. My Dad, Yogi is Dale's tribute to his dad–a treat for baseball fans and fathers and sons everywhere.

Yogi Berra was the backbone of the New York Yankees through ten World Series Championships. In My Dad, Yogi is Dale Berra chronicles his unshakeable bond with his father, going back to his suburban New Jersey upbringing, his parents’ enduring relationship, and his Dad’s formidable career.

Following in his Dad’s footsteps, Dale came up with the Pittsburgh Pirates, contributing to their 1979 championship season and emerging as one of baseball's most talented young players before eventually uniting with his Dad in the Yankee dugout.

Yogi supported his son throughout his highs of his careers and lows of a drug addiction, eventually staging an intervention that would save Dale's life, and draw the entire family even closer. My Dad, Yogi is Dale's tribute to his dad–a treat for baseball fans and fathers and sons everywhere.

-

"Dale, who had a 10-year MLB stint, reports on his father from a singularly intimate perspective....Dale Berra's memoir both illuminates baseball history and adds to Yogi's life story."The Washington Post

-

"Dale Berra's My Dad, Yogi lets us in on things we may not have known. But this endearing book also confirms what we always knew: Yogi Berra, the Hall of Famer, the American treasure, was a genuinely wonderful human being."Bob Costas

-

"Baseball is a game that fathers teach their sons how to play. Life lessons are a lot tougher, for that's where they have to both learn from each other. Dale Berra's honest, humorous, and touching story is an intimate look at a relationship that was at times difficult, complicated, and tense, but true to who Yogi Berra was...always loving."Billy Crystal

-

"My Dad, Yogi is a beautifully depicted love story between Father and Son. Dale shares funny and unique reflections of what it was like growing up in the shadow of one of the most recognizable and beloved public figures of all time. I had such great respect for Yogi as a New York Yankee. I had tremendous adoration for Yogi as a Man. Dale captures the essence of both in this book."Joe Torre

-

"Dale Berra hits it out of the park with his memoir...The youngest son has an important tale to tell of how his love of family helped him triumph, and that is a grand slam."The New Jersey Star-Ledger

-

"Touching on everything from Yogi's career and personal life to his relationship with Dale, My Dad, Yogi gives an intimate look at the life of an American icon."AskMen.com, Best Books for Father's Day

-

"A short, winsome memoir and biography of a winning American icon."Library Journal

-

"Candid...a loving reflection on his famous father's achievements as baseball legend and family man."New Jersey Monthly

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use