By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

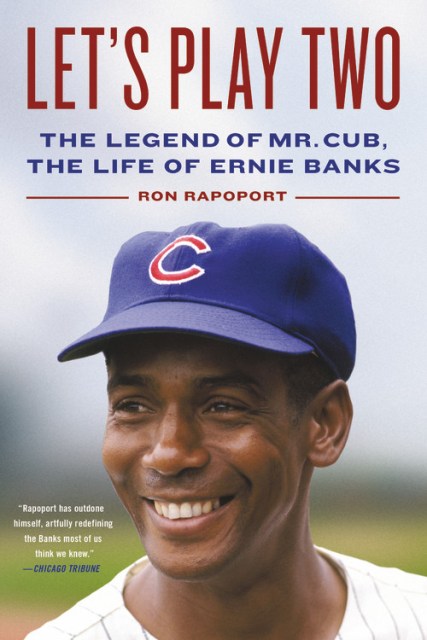

Let’s Play Two

The Legend of Mr. Cub, the Life of Ernie Banks

Contributors

By Ron Rapoport

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Mar 3, 2020

- Page Count

- 464 pages

- Publisher

- Grand Central Publishing

- ISBN-13

- 9780316318624

Price

$24.99Price

$31.99 CADFormat

Format:

- Trade Paperback $24.99 $31.99 CAD

- ebook $11.99 $14.99 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged) $31.99

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around March 3, 2020. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

Ernie Banks, the first-ballot Hall of Famer and All-Century Team shortstop, played in fourteen All-Star Games, won two MVPs, and twice led the Major Leagues in home runs and runs batted in. He outslugged Willie Mays, Hank Aaron, and Mickey Mantle when they were in their prime, but while they made repeated World Series appearances in the 1950s and 60s, Banks spent his entire career with the woebegone Chicago Cubs, who didn’t win a pennant in his adult lifetime.

Today, Banks is remembered best for his signature phrase, “Let’s play two,” which has entered the American lexicon and exemplifies the enthusiasm that endeared him to fans everywhere. But Banks’s public display of good cheer was a mask that hid a deeply conflicted, melancholy, and often quite lonely man. Despite the poverty and racism he endured as a young man, he was among the star players of baseball’s early days of integration who were reluctant to speak out about Civil Rights. Being known as one of the greatest players never to reach the World Series also took its toll. At one point, Banks even saw a psychiatrist to see if that would help. It didn’t. Yet Banks smiled through it all, enduring the scorn of Cubs manager Leo Durocher as an aging superstar and never uttering a single complaint.

Let’s Play Two is based on numerous conversations with Banks and on interviews with more than a hundred of his family members, teammates, friends, and associates as well as oral histories, court records, and thousands of other documents and sources. Together, they explain how Banks was so different from the caricature he created for the public. The book tells of Banks’s early life in segregated Dallas, his years in the Negro Leagues, and his difficult life after retirement; and features compelling portraits of Buck O’Neil, Philip K. Wrigley, the Bleacher Bums, the doomed pennant race of 1969, and much more from a long-lost baseball era.

Today, Banks is remembered best for his signature phrase, “Let’s play two,” which has entered the American lexicon and exemplifies the enthusiasm that endeared him to fans everywhere. But Banks’s public display of good cheer was a mask that hid a deeply conflicted, melancholy, and often quite lonely man. Despite the poverty and racism he endured as a young man, he was among the star players of baseball’s early days of integration who were reluctant to speak out about Civil Rights. Being known as one of the greatest players never to reach the World Series also took its toll. At one point, Banks even saw a psychiatrist to see if that would help. It didn’t. Yet Banks smiled through it all, enduring the scorn of Cubs manager Leo Durocher as an aging superstar and never uttering a single complaint.

Let’s Play Two is based on numerous conversations with Banks and on interviews with more than a hundred of his family members, teammates, friends, and associates as well as oral histories, court records, and thousands of other documents and sources. Together, they explain how Banks was so different from the caricature he created for the public. The book tells of Banks’s early life in segregated Dallas, his years in the Negro Leagues, and his difficult life after retirement; and features compelling portraits of Buck O’Neil, Philip K. Wrigley, the Bleacher Bums, the doomed pennant race of 1969, and much more from a long-lost baseball era.

-

"Rapoport has outdone himself, artfully redefining the Banks most of us think we knew."Rick Kogan, The Chicago Tribune

-

"Well told...an extensively researched portrayal of the public figure as well as the lesser-known, private Banks."The Washington Post

-

"Growing up, every kid I knew wanted to be Ernie Banks, Chicago's 'Mr. Cub.' But there was much more to Ernie than his MVP seasons or his famously sunny outward demeanor. Let's Play Two captures the best of Banks' playing moments, but also delves deeply into a man who did not seem to want you to know more than you could see. Rapoport, a legendary Chicago sportswriter, has written a fascinating, readable, and impeccably researched book about a man who was a Hall of Famer, but also a decided creature of his times."Scott Turow

-

"This is a wonderful book worthy of all the energy and vitality Ernie Banks brought to his remarkable career. But it is also a revealing portrait of the often difficult life of a black ballplayer in America and the often lonely man imprisoned and isolated by his exuberant outer image."Ken Burns

-

"Mr. Rapoport works diligently to penetrate the curtain of enthusiasm in which Banks wrapped himself.... [Let's Play Two] thoughtfully examines the role of race as it crossed Banks's life and career."Wall Street Journal

-

"One of the better sports biographies of the century."National Review

-

"Hooray! Ernie Banks now has the Hall-of-Fame biography he deserves thanks to Ron Rapoport. This well-researched, beautifully written book is everything a baseball fan could want. Cubs fans, of course, will want to buy two."Jonathan Eig, the author of Luckiest Man: The Lifeand Death of Lou Gehrig and Ali: A Life

-

"Rapoport, a 20-year veteran sports columnist for the Chicago Sun-Times, delivers what is sure to be the definitive biography of Chicago Cubs baseball player Ernie Banks...This marvelous look at the life of a beloved athlete should be essential reading for baseball fan."Publishers Weekly (starred review)

-

"Ernie Banks crossed the bridge from a segregated nation and national pastime to a better place, smiling all the way. Although his smile was real, so were the scarring experiences he smiled through. He was more complicated and interesting than the human sunbeam he chose to resemble. With a reporter's diligence and a historian's sensibility, Ron Rapoport tells Banks's story, and that of the different nations at the two ends of the bridge."George F. Will

-

"[An] excellent new biography of Banks."The Hardball Times

-

"This is the definitive biography of baseball's Mr. Sunshine, and Ron Rapoport is the one writer who knew him best and could tell it like it was -- including the 'other side of sunshine.'"Bill Madden, author of Steinbrenner: The Last Lionof Baseball

-

"Famed sportwriter Ron Rapoport's new biography, Let's Play Two, provides a lot of laugh, a few tears, and helps us better understand the great Ernie Banks."WBEZ Chicago

-

"Let's Play Two peels back the complexities of baseball legend Ernie Banks....marvelously brings readers into dugouts and locker rooms....Rapoport meticulously leaves no ball unturned in telling the two stories of Banks' life - as the Legend , and as a very private individual....Let's Play Two is a must read for baseball fans of all ages."Utica Observer-Dispatch

-

"Let's Play Two is a great baseball book, ranking with other outstanding contemporary baseball biographies."Illinois Times

-

"Ron Rapoport has done a magnificent job lifting the veil and illuminating the shadows in Let's Play Two: The Legend of Mr. Cub, the Life of Ernie Banks....Rapoport goes at his subject with a reporter's eye, filling Let's Play Two with details that should be a revelation to many, though some will merely jog the memories of older die-hard Cubs fans."Phil Rosenthal, Chicago Tribune

-

"The dichotomy between Banks's public persona of 'Mr. Cub' and the reality of a man whose career was defined by losing and his later years by loneliness is what's at stake in an engrossing new biography of Banks from the former Chicago sportswriter Ron Rapoport."Jon Greenberg, The Athletic

-

"Rapoport's years of rapport with Banks manifests itself in the completion of a previously unfinished project, now much richer than the original intent because of updated perspective. In his acknowledgements, Rapoport, a former L.A. Times and L.A. Daily News columnist, writes that those who helped him finish this knew Banks as a 'joyful, melancholy, humble, complicated, companionable, lonely man...[who] remained imprisoned in an image of one simplistic dimension.'"Tom Hoffarth, Los Angeles Times

-

"This bio of Ernie Banks is a must read. Let's Play Two, by Ron Rapoport is a beautifully written book that captures the good and the bad, the happy and the sad, of Ernie's life. Cubs fans of a certain age will love this book. I give it my highest recommendation, it's that good."Bruce Miles, Arlington (IL) Daily

-

"An excellent and detailed history of one of baseball's greatest stars and one of the game's most beloved and misunderstood personalities. Let's Pay Two is a great read for baseball fans in general and Cubs fans in particular. The definitive biography of 'Mr. Cub.'"Andrew Elias, Ft. Myers Magazine

-

"A refreshing sports biography that punctures common myths about one of baseball's greats."Kirkus Reviews

-

"[Banks's] era couldn't have been illustrated any better...Rapoport paints a sobering portrait of a man who was ebullient on the outside -- 'let's play two' -- but suffering on the inside."Forbes

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use