By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

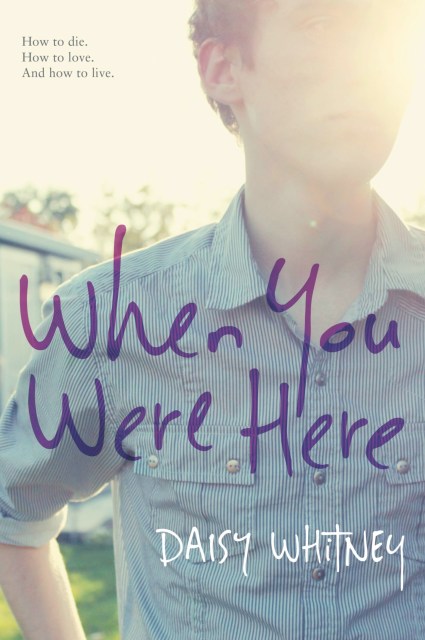

When You Were Here

Contributors

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Jun 24, 2014

- Page Count

- 272 pages

- Publisher

- Little, Brown Books for Young Readers

- ISBN-13

- 9780316209755

Price

$9.00Price

$11.00 CADFormat

Format:

Trade Paperback $9.00 $11.00 CADThis item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around June 24, 2014. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

Danny’s mother lost her five-year battle with cancer three weeks before his graduation-the one day that she was hanging on to see.

Now Danny is left alone, with only his memories, his dog, and his heart-breaking ex-girlfriend for company. He doesn’t know how to figure out what to do with her estate, what to say for his Valedictorian speech, let alone how to live or be happy anymore.

When he gets a letter from his mom’s property manager in Tokyo, where she had been going for treatment, it shows a side of a side of his mother he never knew. So, with no other sense of direction, Danny travels to Tokyo to connect with his mother’s memory and make sense of her final months, which seemed filled with more joy than Danny ever knew. There, among the cherry blossoms, temples, and crowds, and with the help of an almost-but-definitely-not Harajuku girl, he begins to see how it may not have been ancient magic or mystical treatment that kept his mother going. Perhaps, the secret of how to live lies in how she died.

-

Praise for When You Were Here:"A poignant coming-of-age story intertwining loss and hope against a background of Japanese culture...Themes of prescription drug abuse, death and teen pregnancy make this a heavy go, but they don't drag the text down, as they are expertly balanced by Kana's spunk, Danny's pained but authentic voice, and the overarching theme of love."Kirkus Reviews

-

"[An] evocative novel about living life to the fullest...Set against the colorful backdrop of Tokyo's bustling streets, this intricate story vibrantly depicts the stages of Danny's enlightenment and celebrates his mother's sanguine attitude toward life, love, and death."Publishers Weekly

-

"Danny's journey to healing is heartbreaking, hopeful, and full of luminescent beauty... This gem of a book will lead readers to ponder life, love, death, and everything in between."School Library Journal

-

"Despite the sad topic, it's refreshing to read a story centered on a boy's love for his mother."Booklist

-

"The book enticingly combines violin-worthy levels of loss with Danny's vigor and solid testosterone levels..."BCCB

-

Praise for The Mockingbirds:Publishers Weekly (Starred Review)

* "First-time author Whitney boldly addresses date rape, vigilantism, and academic politics in an intense and timely novel... Besides showing skill in executing suspense and drama, Whitney masterfully evokes the complexity of her protagonist's emotions, particularly her intense longing to feel 'normal' again." -

"[Whitney] writes with smooth assurance and a propulsive rhythm as she follows Alex through the Mockingbird's trial process and its accompanying emotional storm of confusion, shame, fear, and finally, empowerment. Authentic and illuminating, this strong debut explores vital teen topics of sex and violence; crime and punishment; ineffectual authority; and the immeasurable, healing influence of friendship and love."Booklist

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use