By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

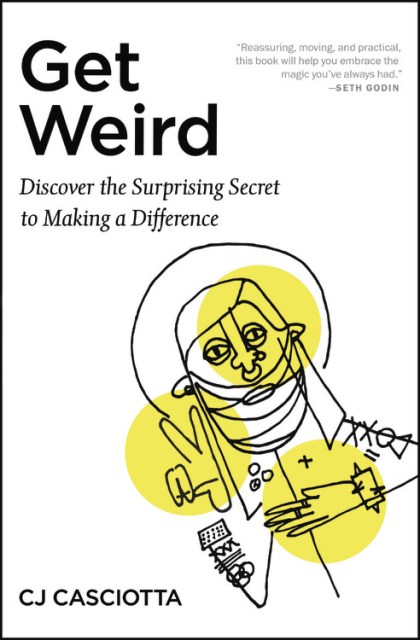

Get Weird

Discover the Surprising Secret to Making a Difference

Contributors

By CJ Casciotta

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Sep 11, 2018

- Page Count

- 240 pages

- Publisher

- FaithWords

- ISBN-13

- 9781546031918

Price

$19.99Price

$25.99 CADFormat

Format:

- Trade Paperback $19.99 $25.99 CAD

- ebook $9.99 $11.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around September 11, 2018. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

What if your weirdness was the key to changing everything? What if the outrageous, imaginative, crazy ideas that live inside your wildest dreams are actually there on purpose, divinely preinstalled to help others?

Knowing what makes you weird is the best thing you can offer your art, your business, your friends, your family, and yourself. It’s the essence of creativity, the stuff of movements, and the hope for humanity. It’s time to quit painting by numbers, conforming to patterns, and checking off boxes. It’s time to Get Weird.

-

It's courageous and wildly creative, giving a voice to the misfit and make-believer in us all.Richard Rohr

-

A soulful invitation to start imagining again and, along the way, rediscovering who we were actually created to be. What a gift!Shauna and Aaron Niequist

-

Whip-smart and full of heart, it is a needed wake-up call, an inspiring invitation to be unusual . . . I can't wait to see all the goodness that's unleashed in the world because of this weird and wonderful book.Brad Montague, writer, director, and creator of Kid President

-

This soulful and practical gem of a book will kickstart your imagination and embolden your heart. While the message in GET WEIRD will stay with you forever, you'll for sure give your copy away to a fellow weirdo. Better buy two now.Ian Morgan Cron, author of The Road Back to You

-

A gifted poet who believes in the soul, CJ and his inspiring book teaches us gradually about our own special gift of weirdness and how it can help minds change and communities heal. It's a huge gift to read his stories and walk with him as he discovers that being a square peg in a round hole keeps you from sinking. You will be blessed by this work.Becca Stevens, founder of Thistle Farms and Episcopal priest

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use