Promotion

Use code MOM24 for 20% off site wide + free shipping over $45

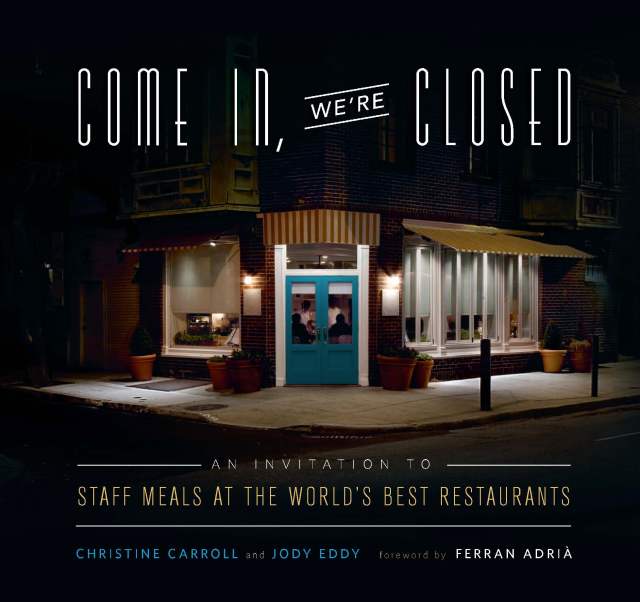

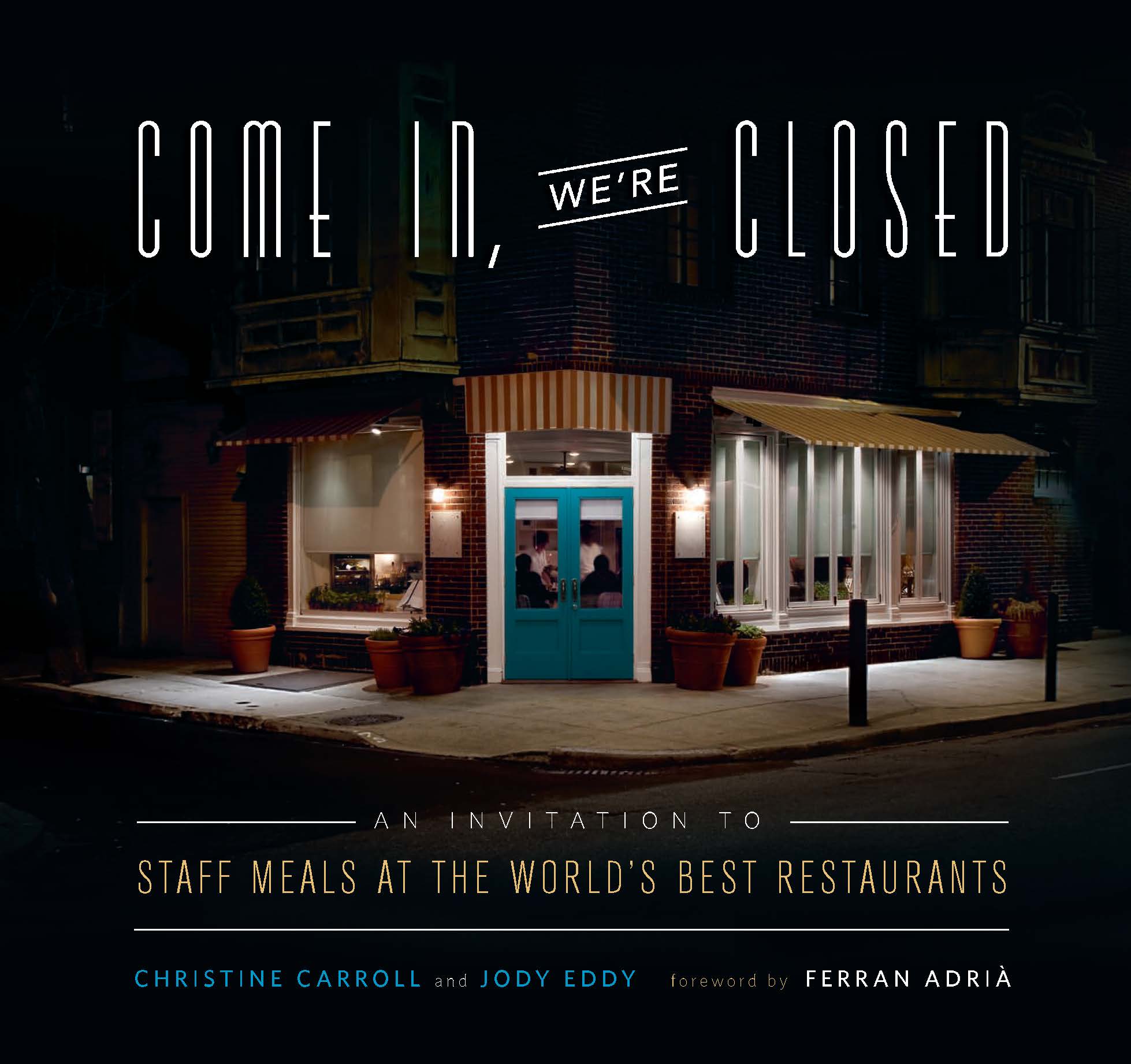

Come In, We're Closed

An Invitation to Staff Meals at the World's Best Restaurants

Contributors

By Jody Eddy

Foreword by Ferran Adria

Formats and Prices

Price

$19.99Price

$25.99 CADFormat

Format:

ebook $19.99 $25.99 CADThis item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around October 2, 2012. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

Join authors Christine Carroll and Jody Eddy as they share these intimate staff meal traditions, including exclusive interviews and never-before-recorded recipes, from twenty-five iconic restaurants including: Ad Hoc in Napa, California; Mugaritz in San Sebastian, Spain; The Fat Duck in London, England; McCrady’s in Charleston, South Carolina; Uchi in Austin, Texas; Michel et Sebastien Bras in Laguiole, France; wd~50 in New York City, New York, and many more.

Enjoy more than 100 creative and comforting dishes made to sate hunger and nourish spirits, like skirt steak stuffed with charred scallions; duck and shrimp paella; beef heart and watermelon salad; steamed chicken with lily buds; Turkish red pepper and bulgur soup; homemade tarragon and cherry soda; and buttermilk doughnut holes with apple-honey caramel glaze. It’s finally time to come in from the cold and explore the meals that fuel the hospitality industry; your place has been set.

Genre:

- On Sale

- Oct 2, 2012

- Page Count

- 320 pages

- Publisher

- Running Press

- ISBN-13

- 9780762447077

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use