By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

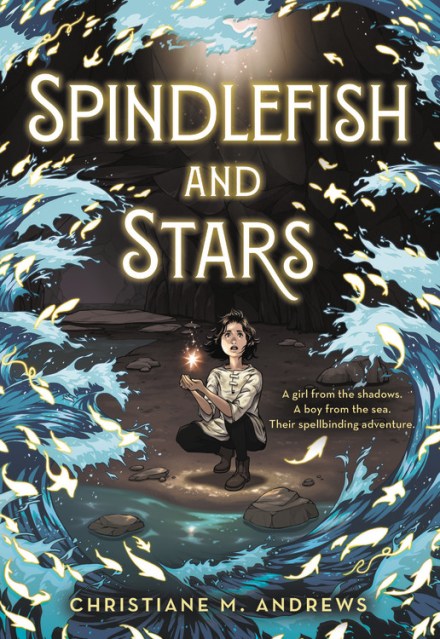

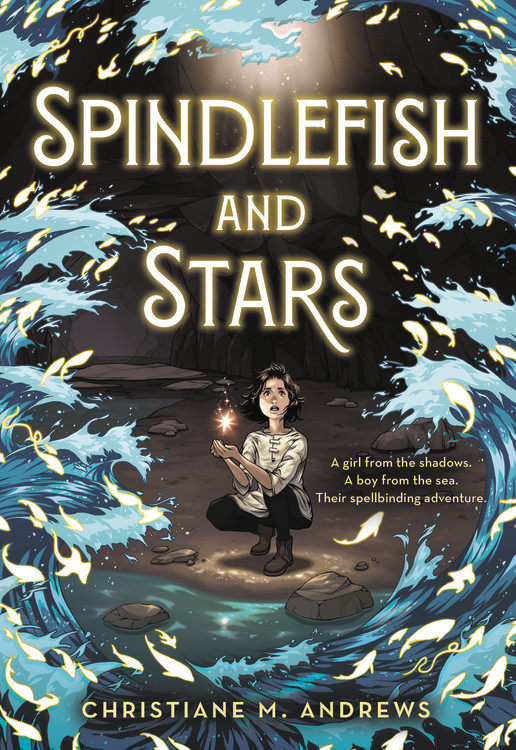

Spindlefish and Stars

Contributors

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Oct 19, 2021

- Page Count

- 400 pages

- Publisher

- Little, Brown Books for Young Readers

- ISBN-13

- 9780316496032

Price

$7.99Price

$11.99 CADFormat

Format:

- Trade Paperback $7.99 $11.99 CAD

- ebook $7.99 $9.99 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged)

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around October 19, 2021. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

This spellbinding fantasy about a girl from the shadows and a boy from the sea is perfect for fans of The Girl Who Drank the Moon and The Book of Boy.

Clo is quickly locked away and made to spend her days in unnerving chores with the island’s extraordinary fish, while the old woman sits nearby weaving an endless gray tapestry. Frustrated and aching with the loss of her father, Clo must unravel the mysteries of the island and all that’s hidden in the vast tapestry’s threads—secrets both exquisite and terrible. And she must decide how much of herself to give up in order to save those she thought she’d lost forever.

Inspired by Greek mythology, Spindlefish and Stars invites readers to seek connections, to forge their own paths, and to explore the power of storytelling in our interwoven histories.

-

* "An epic tale of abandonment, travel, secrets, family, and the meaning of art.... Exquisite in detail.... A tapestry, both humble and rich."Kirkus Reviews, starred review

-

* "A lyrical debut exploring the nature of destiny and sacrifice.... The narrative voice...makes this enchanting story feel like an all-new myth built from classic material."Publishers Weekly, starred review

-

"Expertly written, full of beautiful imagery and elements of Greek mythology.... An engaging and inventive novel."School Library Journal

-

* "Readers familiar with Greek myth will take special pleasure in the slantwise view Andrews conjures.... The tapestry metaphor also offers a longer, measured view of the unavoidability of pain and the beauty of kindness as well as commentary on the persistence of powerful stories through art."BCCB, starred review

-

* "Bewitching, beautiful, and bewildering.... Immensely satisfying."Booklist, starred review

-

"Both mysterious and evocative.... A dreamy, immersive story that raises questions aboutthe power of art and the value of humansuffering."The Horn Book

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use