Promotion

Use code MOM24 for 20% off site wide + free shipping over $45

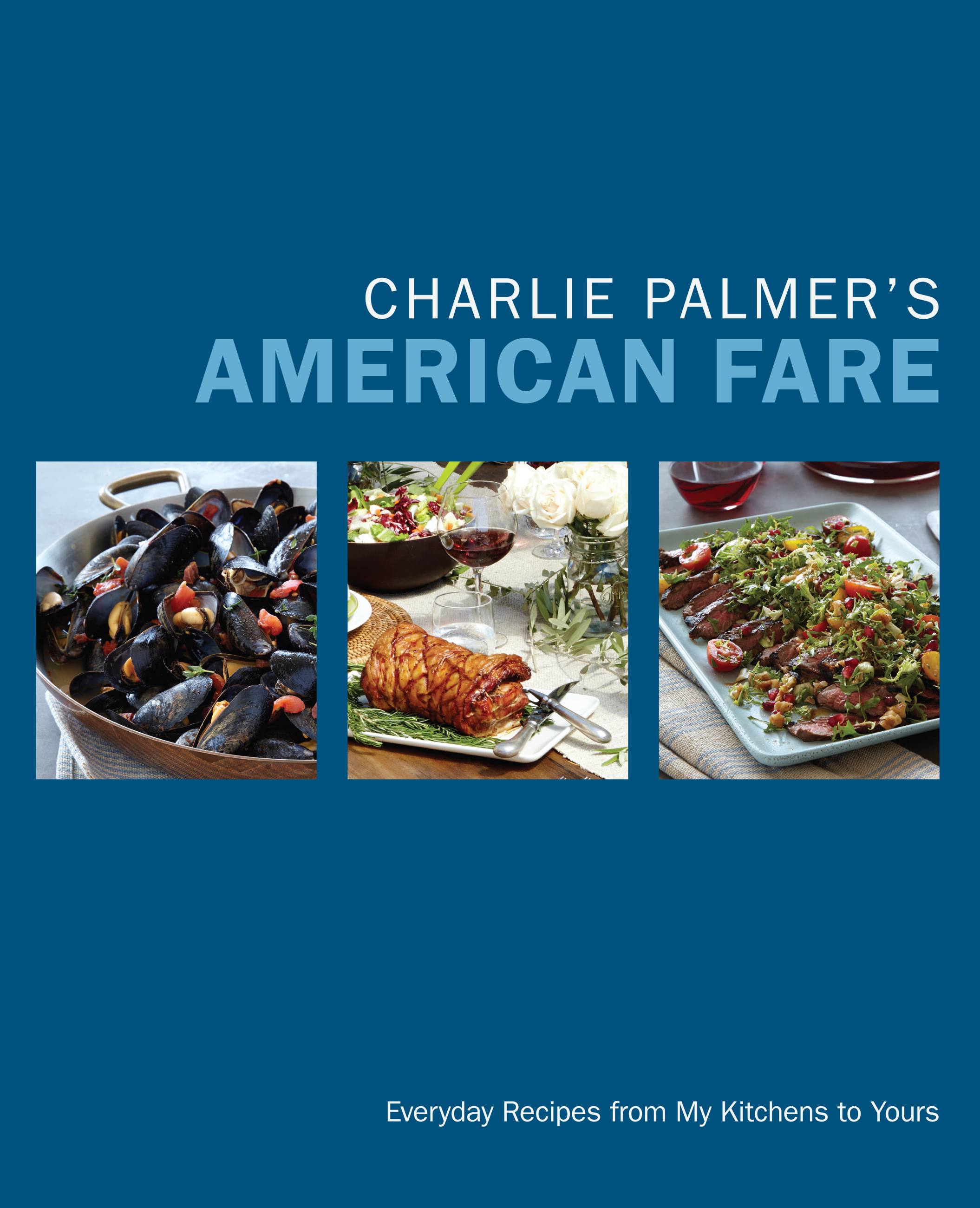

Charlie Palmer's American Fare

Everyday Recipes from My Kitchens to Yours

Contributors

Formats and Prices

Price

$19.99Price

$25.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $19.99 $25.99 CAD

- Hardcover $40.00 $44.00 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around April 28, 2015. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

Palmer has been at the forefront of great American food since the ’80s. Fresh local ingredients, bursts of flavor, and preparation with ease have been the hallmark of his cooking over the years, and this collection includes the best recipes he cooks at home and his restaurants. Included will be over 100 recipes that any cook can make with ease-from Charlie’s Famous Corn Chowder with Shrimp to Cheese Strata to Prosciutto-Wrapped Zucchini to Baked Lemon Chicken; plus snacks like Crispy Chickpeas and desserts like Double-Trouble Chocolate Chip Cookies, Lemon Shortbread and Fig Crostata. Along with personal reflections on food and family from one of America’s own top chefs, this cookbook will help every family with delicious, easy dinner ideas.

Genre:

- On Sale

- Apr 28, 2015

- Page Count

- 288 pages

- Publisher

- Grand Central Life & Style

- ISBN-13

- 9781455531004

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use