By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

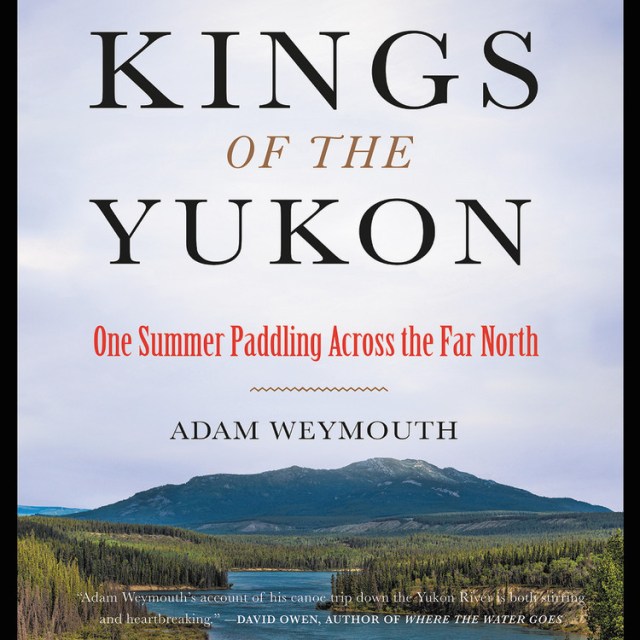

Kings of the Yukon

One Summer Paddling Across the Far North

Contributors

Read by Charlie Anson

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- May 15, 2018

- Publisher

- Hachette Audio

- ISBN-13

- 9781478941040

Format

Format:

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged)

- ebook $11.99

- Trade Paperback $21.99 $28.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around May 15, 2018. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

The Yukon river is 2,000 miles long, the longest stretch of free-flowing river in the United States. In this riveting examination of one of the last wild places on earth, Adam Weymouth canoes along the river’s length, from Canada’s Yukon Territory, through Alaska, to the Bering Sea. The result is a book that shows how even the most remote wilderness is affected by the same forces reshaping the rest of the planet.

Every summer, hundreds of thousands of king salmon migrate the distance of the Yukon to their spawning grounds, where they breed and die, in what is the longest salmon run in the world. For the communities that live along the river, salmon was once the lifeblood of the economy and local culture. But climate change and a globalized economy have fundamentally altered the balance between man and nature; the health and numbers of king salmon are in question, as is the fate of the communities that depend on them.

Traveling along the Yukon as the salmon migrate, a four-month journey through untrammeled landscape, Adam Weymouth traces the fundamental interconnectedness of people and fish through searing and unforgettable portraits of the individuals he encounters. He offers a powerful, nuanced glimpse into indigenous cultures, and into our ever-complicated relationship with the natural world. Weaving in the rich history of salmon across time as well as the science behind their mysterious life cycle, Kings of the Yukon is extraordinary adventure and nature writing at its most urgent and poetic.

“Kings of the Yukon succeeds as an adventure tale, a natural history and a work of art.”-Wall Street Journal

Genre:

-

- Winner of The Sunday Times/ Peters Fraser+ Dunlop 2018 Young Writer of the Year Award

- Shortlisted for the Royal Society of Literature (RSL) Ondaatje Prize

- Named the Lonely Planet Adventure Travel Book of the Year

- Named a notable book for the 2018 Sigurd F. Olson Nature Writing Award

-

"[A] brilliant account of a summer spent paddling the 2,000-mile length of the Yukon River...Kings of the Yukon succeeds as an adventure tale, a natural history and a work of art. Its various threads of context and back story are woven seamlessly into the daily panorama of the river journey."Richard Adams Carey, Wall Street Journal

-

"Weymouth paddled the length of the Yukon River to learn about king salmon. In his eloquent account of his experiences, he sheds light on the life cycle of these magnificent creatures, the complexities of the landscape, and the humans and other animals inhabiting it."San Francisco Chronicle

-

"Timely...Weymouth's prose is often beautiful, bringing to life the river and its inhabitants."Anchorage Daily News

-

"It feels as if we have found, ready minted and hidden in plain sight, a really outstanding new contemporary British voice...Weymouth combines acute political, personal and ecological understanding, with the most beautiful writing reminiscent of a young Robert Macfarlane... He is, I have no doubt, a significant voice for the future."Andrew Holgate, The Sunday Times

-

"In this lyrical debut, Adam Weymouth canoes the length of the river to watch the fish and meet the communities who have relied on them, but are now struggling as stocks fall."Financial Times

-

"A dose of adventure and environmental science . . . dynamic"Southern Living, Best New Books to Read in May

-

"Adam Weymouth writes well. He is poetic, but also precise....This is a rich and fascinating book."Elisa Segrave, The Spectator (UK)

-

"a richly told history of one of North America's most remote wildernesses"Publishers Weekly, Starred Review

-

"In this timely story 'of relationships, of the symbiosis of people and fish, of the imprint that one leaves on the other,' Weymouth keeps the pages turning to the very end."Kirkus

-

"The writing is lyrical, whether describing a gull in the wind, the difference between nomadism and restlessness, the symbiosis of people and fish, or the slow amble of Prudhoe Bay's oil down the Trans-Alaska Pipeline. Equal parts natural history, travelog, and cultural history, this work will appeal to readers of all three genres, especially fans of John McPhee."Library Journal

-

"A gripping story about one of the last great salmon runs on the planet."North State Public Radio

-

"Adam Weymouth's account of his canoe trip down the Yukon River is both stirring and heartbreaking. He ably describes a world that seems alternately untouched by human beings and teetering at the brink of ruin."David Owen, staff writer, The New Yorker, and author of Where the Water Goes

-

"An enthralling account of a literary and scientific quest. Adam Weymouth vividly conveys the raw grandeur and deep silences of the Yukon landscape, and endows his subject, the river's king salmon, with a melancholy nobility."Luke Jennings, author of Blood Knots

-

"Adam Weymouth writes of the Yukon River, the salmon and the people, with language that flows and ripples like the water he describes. There may be a smoothness to the words, but pay attention, there are deep undercurrents here. You can hear the water dripping from his paddle between each stroke as he travels that river. It mingles with the voices of the many people he visits along its shores."Harold Johnson author of several books including Firewater: How Alcohol Is Killing My People (and Yours)

-

"Shift over Pierre Berton and Farley Mowat. You, too, Robert Service. Set another place at the table for Adam Weymouth, who writes as powerfully and poetically about the Far North as any of the greats who went before him."Roy MacGregor, author of Original Highways: Travelling the Great Rivers of Canada

-

"Beautiful, restrained, uncompromising. The narrative pulls you eagerly downstream roaring, chuckling and shimmering just like the mighty Yukon itself."Ben Rawlence, author of City of Thorns

-

"A moving, masterful portrait of a river, the people who live on its banks, and the salmon that connect their lives to the land. It is at once travelogue, natural history, and a meditation on the sort of wildness of which we are intrinsically a part. Adam Weymouth deftly illuminates the symbiosis between humans and the natural world-a relationship so ancient, complex, and mysterious that it just might save us."Kate Harris, author of Lands of Lost Borders

-

"I thoroughly enjoyed traveling the length of the Yukon River with Adam Weymouth, discovering the essential connection between the salmon and the people who rely upon them. What a joy it is to be immersed in such a remote and wondrous landscape, and what a pleasure to be in the hands of such a gifted narrator."Nate Blakeslee, author of American Wolf

-

"This is the best kind of travel writing. Weymouth embarks on an ambitious journey-2,000 miles down the Yukon in a canoe-voyaging, listening, and learning. An outstanding book."Rob Penn, author of The Man Who Made Things Out of Trees

-

"Written with great care and affection, this account of canoeing the length of the Yukon reads like an infatuated love letter to the river."Chris Fitch, Geographical

-

"Adam Weymouth's account of his journey down the Yukon is truly an epic...eloquent and tautly written."Tom Fort, Literary Review

-

"You suspect [Paul] Theroux would be intrigued by Adam Weymouth's journey up the Yukon in a canoe, following the salmon migration. Part-adventure, part-investigation."Wanderlust

-

"As a travel tale the book is first-rate. But Weymouth's keen interest in the Chinook - aka King - Salmon, and his listening skills when he meets dozens of river-dwellers whose cultures have been shaped by the migrations of this fish, combine to fascinating, awe-inspiring, and often heart-breaking effect."Bart Hawkins Kreps, An Outside Chance

-

"Brilliant...one of the most effective climate change stories I've read"National Observer

-

"The book sparkles like river water in sunlight as it traces the journeying leaps of salmon and people"Royal Society of Literature (RSL) Ondaatje Prize committee

-

"Weymouth combines acute political, personal and ecological understanding, with the most beautiful writing reminiscent of a young Robert Macfarlane ... He is, I have no doubt, a significant voice for the future"Andrew Holgate

-

"Lyrical ... The elegiac tone that fills Kings of the Yukon, the sorrow at the loss of culture and nature in the wilderness, is an unavoidable reflection of life in the 21st century."Richard Lea, Guardian

-

"This is the best kind of travel writing. Weymouth embarks on an ambitious journey - 2,000 miles down the Yukon in a canoe - voyaging, listening and learning. An outstanding book."Rob Penn, author of The Man Who Made Things Out of Trees

-

"[A] brilliant account of a summer spent paddling the 2,000-mile length of the Yukon River ... Kings of the Yukon succeeds as an adventure tale, a natural history and a work of art."Richard Adams Carey, Wall Street Journal

-

"Dazzling, often in unexpected ways, Adam Weymouth is a nuanced examiner of some of the world's most fraught and urgent questions about the interconnectedness of people and the natural world."Kamila Shamsie

-

"Adam Weymouth takes his place beside the great travel writers like Chatwin, Thubron, Leigh Fermor, in one bound. But like their books this is about so much more than just travel."Susan Hill

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use