Promotion

Use code SPRING26 for 20% off sitewide.

By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

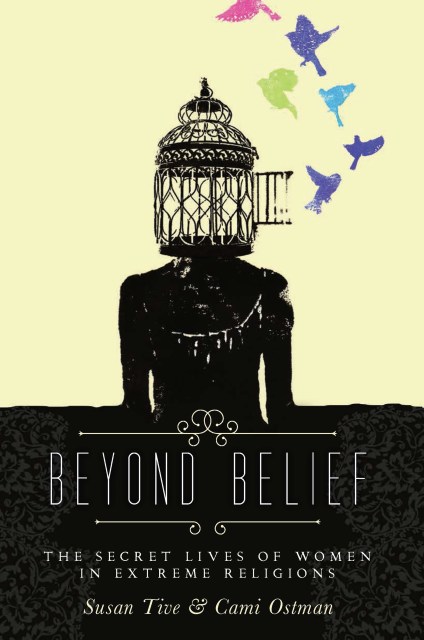

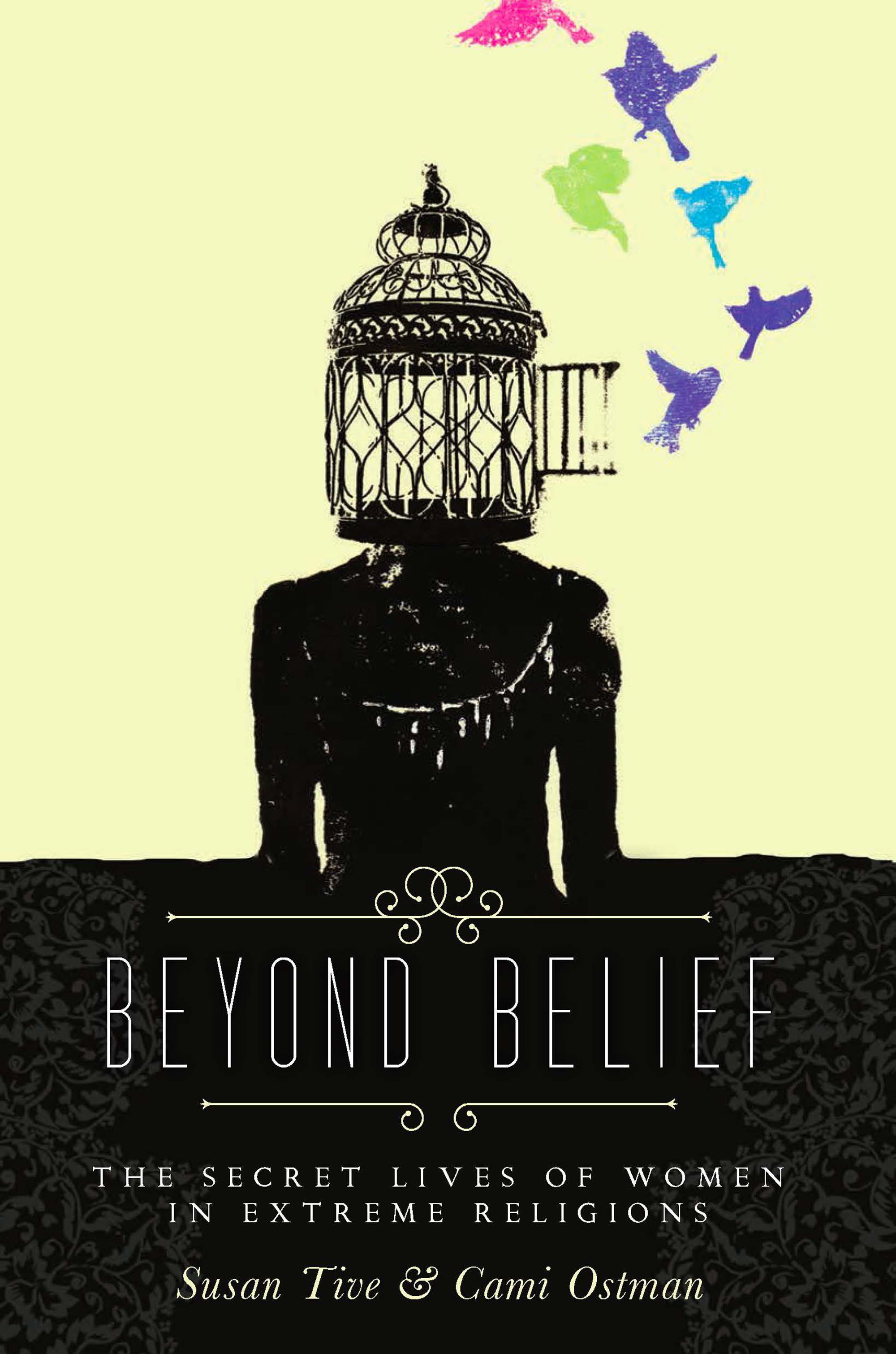

Beyond Belief

The Secret Lives of Women in Extreme Religions

Contributors

Edited by Cami Ostman

Edited by Susan Tive

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Apr 2, 2013

- Page Count

- 224 pages

- Publisher

- Seal Press

- ISBN-13

- 9781580054614

Price

$7.99Price

$9.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $7.99 $9.99 CAD

- Trade Paperback $21.99 $28.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around April 2, 2013. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

Beyond Belief addresses what happens when women of extreme religions decide to walk away.

Editors Susan Tive (a former Orthodox Jew) and Cami Ostman (a de-converted fundamentalist born-again Christian) have compiled a collection of powerful personal stories written by women of varying ages, races, and religious backgrounds who share one commonality: they’ve all experienced and rejected extreme religions. Covering a wide range of religious communities—including Evangelical, Catholic, Jewish, Mormon, Muslim, Calvinist, Moonie, and Jehovah’s Witness—and containing contributions from authors like Julia Scheeres (Jesus Land), the stories in Beyond Belief reveal how these women became involved, what their lives were like, and why they came to the decision to eventually abandon their faiths.

The authors shed a bright light on the rigid expectations and misogyny so often built into religious orthodoxy, yet they also explain the lure—why so many women are attracted to these lifestyles, what they find that’s beautiful about living a religious life, and why leaving can be not only very difficult but also bittersweet.