Promotion

Use code MOM24 for 20% off site wide + free shipping over $45

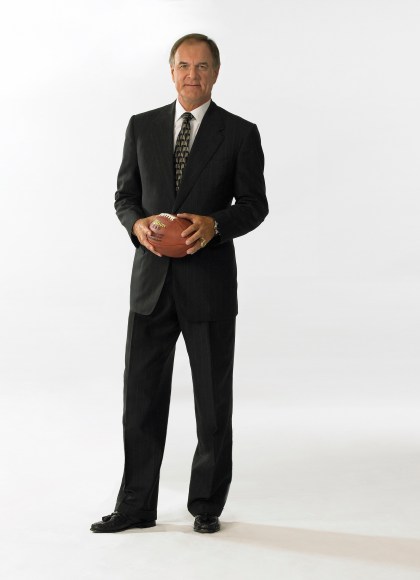

The Q Factor

The Elusive Search for the Next Great NFL Quarterback

Contributors

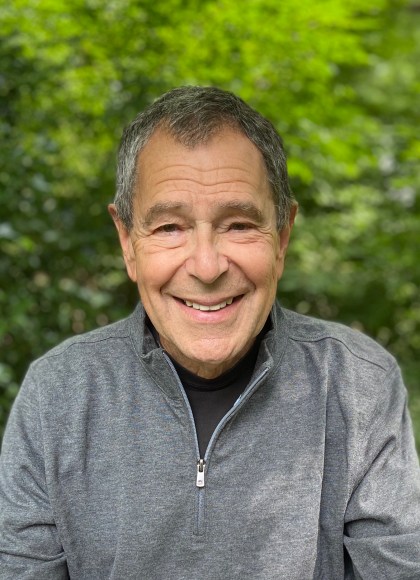

By James Dale

Formats and Prices

Price

$28.00Price

$35.00 CADFormat

Format:

- Hardcover $28.00 $35.00 CAD

- ebook $12.99 $16.99 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged)

- Trade Paperback $17.99 $22.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around September 29, 2020. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

There are elite athletes in every sport — people who possess tangible and intangible qualities that allow them to overcome daunting odds, spot opportunity in the midst of adversity, and turn defeat into victory. No position embodies this dynamic more than football quarterbacks, and nothing is a greater test of performance than the NFL.

The tangibles — metrics, stats, ratings, bowl games, championships — are critical to evaluation. But they’re not enough. Every year, highly rated college quarterbacks are analyzed, critiqued, hyped up and/or doubted, and those who manage to survive the scrutiny are drafted early. Some of those early picks make it to the top, some end up journeymen, and some just wash out. Why? What separates the elites from the pack?

In THE Q FACTOR, former NFL coach Brian Billick takes the highly promising 2018 NFL quarterback Draft class — the most touted class since 2004 (Manning, Roethlisberger, Rivers) and 1983 (Elway, Kelly, Marino) — and measures the top five quarterback picks to gauge how, why, and if they succeed. They are all first rounders, all with sterling college credentials, all talented athletes, all taken by teams betting their futures. One or maybe two could go on to greatness. But which ones, and why? Could the prediction process be better? Are the “experts” looking at the wrong factors? How do we find the best of the best?

That’s what THE Q FACTOR explores…and finally explains.

Genre:

- On Sale

- Sep 29, 2020

- Page Count

- 272 pages

- Publisher

- Twelve

- ISBN-13

- 9781538749920

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use