Promotion

Use code MOM24 for 20% off site wide + free shipping over $45

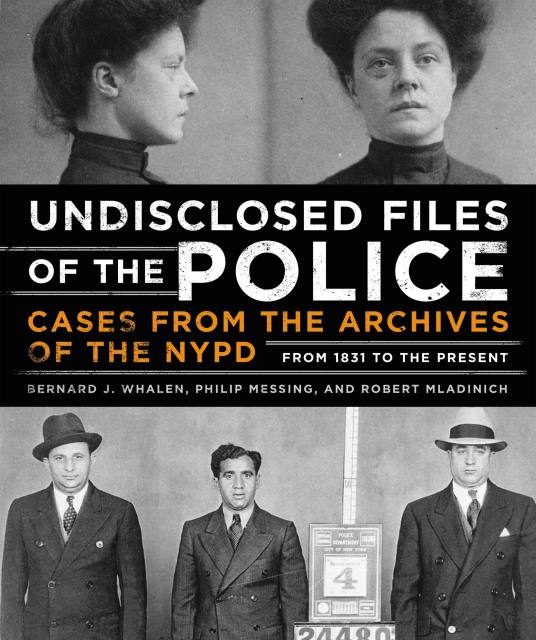

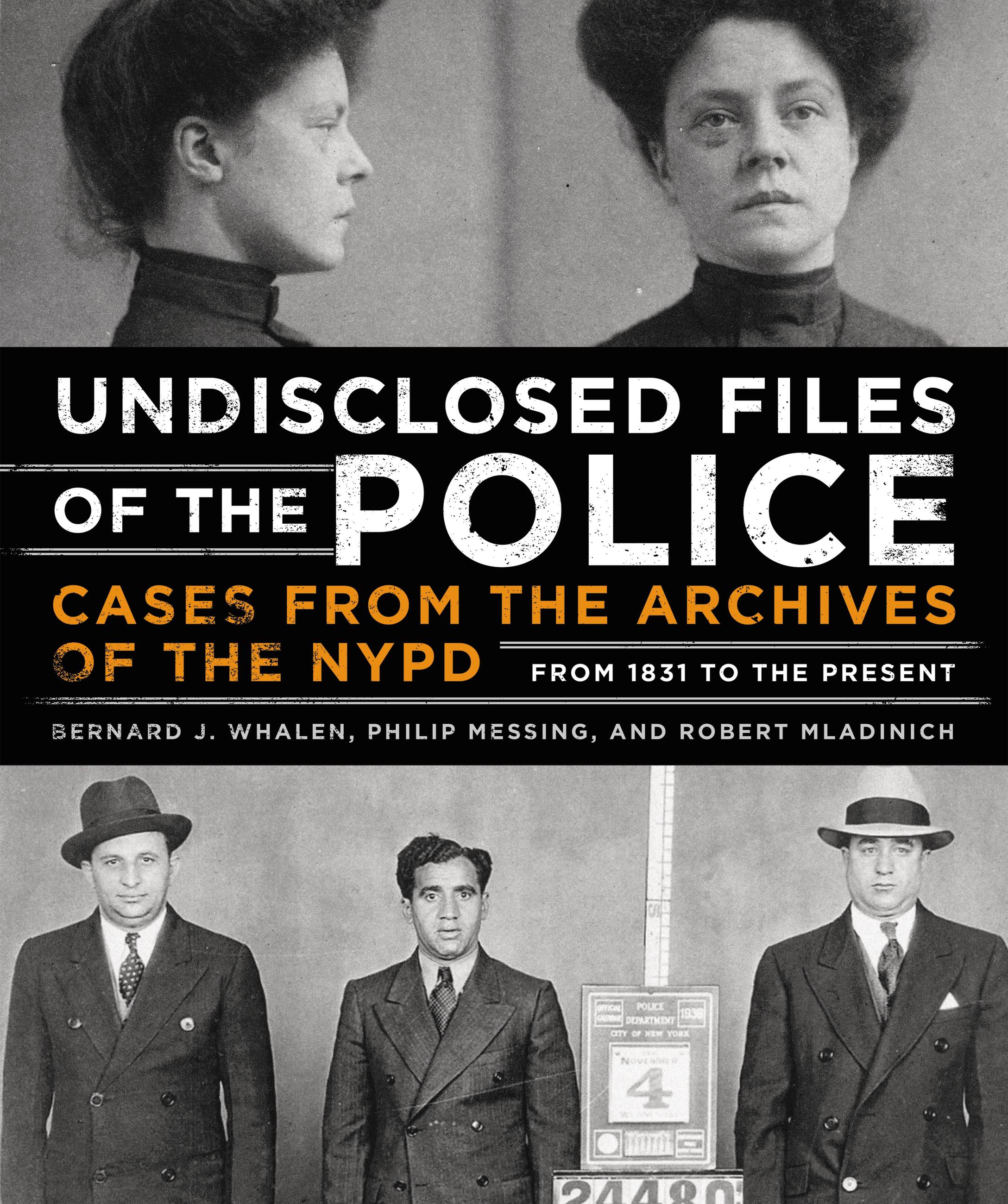

Undisclosed Files of the Police

Cases from the Archives of the NYPD from 1831 to the Present

Contributors

Formats and Prices

Price

$19.99Price

$24.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $19.99 $24.99 CAD

- Hardcover $40.00 $52.00 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged)

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around September 27, 2016. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

From atrocities that occurred before the establishment of New York’s police force in 1845 through the terrorist attack on the World Trade Center in 2001 to the present day, this visual history is an insider’s look at more than 80 real-life crimes that shocked the nation, from arson to gangland murders, robberies, serial killers, bombings, and kidnappings, including:

- Architect Stanford White’s fatal shooting at Madison Square Garden over his deflowering of a teenage chorus girl.

- The anarchist bombing of Wall Street in 1920, which killed 39 people and injured hundreds more with flying shrapnel.

- The 1928 hit at the Park Sheraton Hotel on mobster Arnold Rothstein, who died refusing to name his shooter.

- Kitty Genovese’s 1964 senseless stabbing, famously witnessed by dozen of bystanders who did not intervene.

- Son of Sam, a serial killer who eluded police for months while terrorizing the city, was finally apprehended through a simple parking ticket.

Perfect for crime buffs, urban historians, and fans of Serial and Making of a Murderer, this riveting collection details New York’s most startling and unsettling crimes through behind-the-scenes analysis of investigations and more than 500 revealing photographs.

Genre:

- On Sale

- Sep 27, 2016

- Page Count

- 320 pages

- Publisher

- Black Dog & Leventhal

- ISBN-13

- 9780316431224

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use