Promotion

Use code SPRING26 for 20% off sitewide.

By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

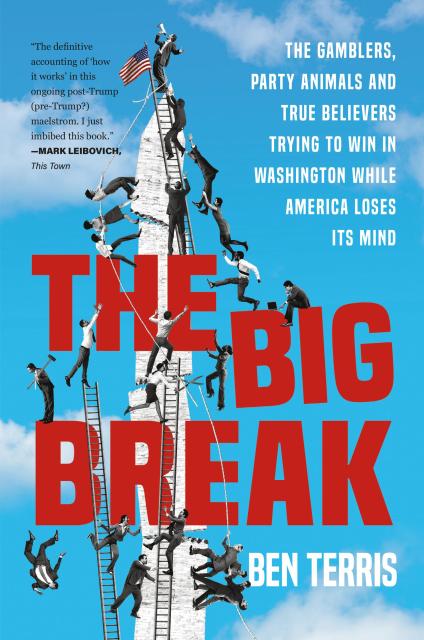

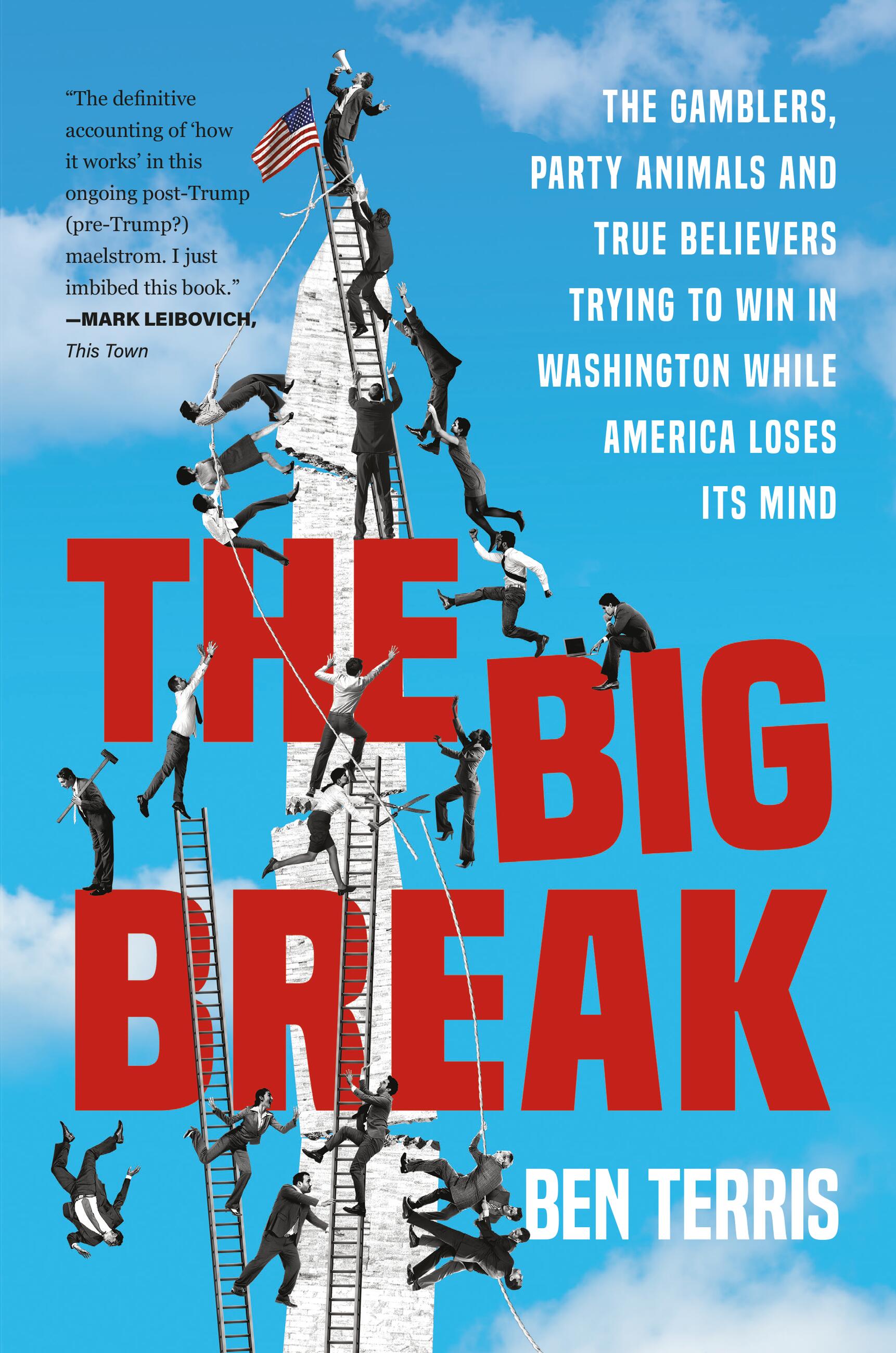

The Big Break

The Gamblers, Party Animals, and True Believers Trying to Win in Washington While America Loses Its Mind

Contributors

By Ben Terris

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Jun 6, 2023

- Page Count

- 352 pages

- Publisher

- Twelve

- ISBN-13

- 9781538708057

Price

$30.00Price

$38.00 CADFormat

Format:

- Hardcover $30.00 $38.00 CAD

- ebook $15.99 $20.99 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged) $27.99

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around June 6, 2023. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

In this fascinating investigation into the real life inner workings of a post-Trump American government, uncover the odd and eccentric personalities grappling for their own bit of power in D.C.

The Big Break investigates how Washington works, and how different kinds of people try to make it work for them. Ben Terris presents an inside history of this crucial moment in Washington, reporting from exclusive parties, poker nights, fundraisers, secluded farms outside town and the halls of Congress; among the oddballs and opportunists and true believers. This book is about the people who see this moment as an opportunity to bet big—on their country or maybe just on themselves. It will take a close look at Washington’s bold-faced names as they try to get their bearings on the post-Trump (and possibly pre-Trump) landscape. And it will introduce readers to the behind-the-scenes players — MAGA pilgrims and Resistance flamekeepers and shapeshifting veterans — who believe they know what Washington, and America, must do if they’re going to survive, or even thrive.

Trump’s arrival in Washington represented a big break in how the city operated. He surrounded himself with outsiders; power structures reorganized around those who knew him or his family and those who could flatter and influence his base. He changed the way the game was played, only it wasn’t actually a game at all. When pro-Trump elements both inside and outside of government plotted to overturn his loss in the 2020 presidential election, the Capitol became a combat zone, then a military fortress.

It was, to put it lightly, a destabilizing time. But how much did the Trump years really change Washington? Has Joe Biden’s presidency heralded a return to normal, as many had hoped? What did ‘normal’ mean before Trump, and what do people think it means now?

The Big Break will follow a cast of D.C. characters in search of answers to these questions. They are a diverse crew—a pollster with a gambling habit, an oil heiress with a big heart, a cowboy lobbyist, a Republican kingmaker who decided to love Trump and his right-hand man who decided he couldn’t any longer. They all share at least one thing in common: They had seen their country go through a Big Break, and they’d come to get theirs.

-

“An intimate, entertaining and damning portrait of the way Washington works, not just now but maybe always.”Washington Post Review

-

"No one gets today's Washington like Ben Terris – in all its particular contours and caricatures. THE BIG BREAK is the definitive accounting of ‘how it works’ in this ongoing post-Trump (pre-Trump?) maelstrom. I just imbibed this book."Mark Leibovich, author of This Town and Thank You for Your Servitude

-

"I thought nothing about Washington's sordid power-and-influence scene could surprise me--until I read Ben Terris's book. With his roguish reporting methods, Ben has revealed something original, entertaining, and profoundly disturbing about the rotting soul of the American political system. If Mark Leibovich's This Town captured Washington in its virtue-signaling heyday, Ben has produced a masterful, vice-spiked sequel for the Trump era and beyond.”Tim Alberta, Staff writer of The Atlantic and author of American Carnage

-

"Many books promise to reveal 'how Washington really works.' THE BIG BREAK actually does—by zooming in not on the principals—the politicians and talking heads—but instead on the worker bees: the staffers who make our capital work each day, a hard to decipher mix of craven opportunists and the true believers who are sometimes one in the same. What happened next can only be understood through the eyes of Ben Terris, one of the most principled and perceptive reporters in Washington, who masterfully guides us through the destabilizing decade that followed the first black presidency."Wesley Lowery, Pulitzer Prize winning journalists and author of American Whitelash: A Changing Nation and the Cost of Progress

-

“This is not just another book about Washington. It’s a wild ride, filled with wit, humor, actual people (not just robotic politicians), and drama—so much drama. I found myself cracking up reading Ben’s wonderful writing, and then also terrified that maybe Democracy was on the verge of cracking up too.”Molly Jong-Fast, special correspondent for Vanity Fair and host of the Fast Politics podcast

-

“Instead of staring at the puppet show of modern Washington, Ben Terris goes behind the curtain to talk to the people pulling the strings, or at least trying to. His subjects are climbers, dreamers, con-artists and true believers, sometimes all four at once. The stories he tells here are oddly comforting, because it turns out these people are just like us, and also terrifying, for exactly the same reason."Peter Sagal, host of NPR’s Wait Wait . . . Don’t Tell Me!

-

"The highest praise I can give of this book is my nearly unbearable professional jealousy upon reading it. THE BIG BREAK offers as authentic a depiction of the Trump-era Washington archetypes as has been put to paper. If you want to understand the true VEEPish underbelly of the Washington Swamp there might not be a better text. Ben's clear-eyed, perceptive assessment of DC is both empathetic and withering and filled with enough gallows humor to keep the reader from descending into utter misery over the state of affairs. I recommend it for DC insiders and outsiders alike."Tim Miller, Author of Why We Did It and MSNBC Political Analyst

-

"Ben Terris is one of maybe only a handful of political reporters who can get into any and every room in Washington. And armed with this skill, he usually walks through the doors other reporters wouldn’t even notice. It makes him a reporter I’ve been professionally jealous of for years, and also the author of a truly spectacular story all about the inner workings of DC that I couldn’t put down.Sam Sanders, host of Vulture's Into It Podcast

Ben has an uncanny ability to make people who shouldn’t trust him at all tell him everything. That can be dangerous for a political operative in DC, but pretty great for anyone who decides to dig into THE BIG BREAK." -

"THE BIG BREAK is a rollicking account of this weird era of American politics, told with Ben Terris’s expert eye for detail and appreciation of great screwball characters. In 2023, you need a guide you can trust, and for that, you can’t do better than Terris."Olivia Nuzzi, Washington correspondent for New York Magazine